- 10 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Innovation in Small Construction Firms

About this book

Innovation in Small Construction Firms promotes the benefits of innovation, and stimulate innovation capability within and between small and medium sized (SMEs) construction firms in an effort to bring in a new 'can innovate, should innovate, want to innovate' culture to the construction industry. Presenting new theoretical and practical insights and models grounded in descriptive case studies, the issues addressed include:

- what is the motivation to innovate?

- what is appropriate innovation?

- how can small construction firms create, manage and exploit innovation?

- what practice-based models, tools and techniques support the capability of small construction firms to innovate well?

- how does this fit in the context of leading international work in construction innovation?

Findings are contextualised in the broader literature to make them of relevance to policy makers, practitioners and researchers interested in small, project-based firms in general.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Innovation in Small Construction Firms by Peter Barrett,Martin Sexton,Angela Lee in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Construction & Architectural Engineering. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction

Characteristics of the construction industry

The construction industry is not homogeneous. It is composed of many diverse competing (and collaborating) firms, the majority of whom are brought together for one, bespoke project, before transferring to other projects. The sector is often characterised by its adversarial behaviour, litigious orientation, poor communication and coordination, lack of customer focus, and its low investment in research and development (Simon, 1944; Emmerson, 1962; Banwell, 1964; Latham, 1994; Egan, 1998; Fairclough, 2002). Within this unfavourable supply context, clients are increasing their demands for improved building performance (both functionally and aesthetically), while at the same time reducing initial capital, and ongoing operational and maintenance costs. Set against an already competitive industry, construction firms are under pressure to develop and/or adopt innovative technologies and practices in order to try to satisfy these demands (Sexton et al., 2005).

The construction industry as a whole has a poor reputation for innovation and is often accused of being slow to adopt new technologies. Further, due to the weak appropriability conditions found in construction, contractors have little to gain from being innovative other than optimising their own processes (Sexton and Barrett, 2005). Economies of scale often do not exist and knowledge gains are rarely transferred (Pries and Janszen, 1995). However, Ball (1988) has argued that the industry is not backward, merely different from other industries – it is an industry that has to ‘innovate’ on a daily basis in order to solve the problems that the design and production phases pose. This stance is supported by Tatum (1984, 1986), Pries and Janszen (1995) and Veshosky (1998), who affirm that construction projects are, by their very nature, inherently innovative: the project-based nature of the industry makes every project unique.

Nam and Tatum (1997) move the debate along by suggesting that the lack of innovation may not be attributed to the lack of capability, but to the absence of a coordinated effort to link market needs and inventive capacity in spite of adequate demand pull as well as a supply of promising technologies, such as computers, robotics and advance materials that are ready to be utilised through a coordinated system. Further, Reichstein et al. (2005) report that construction firms are less open to the external environment and tend to have poorly developed research and development (R&D), with low capacity to absorb practices from other sectors.

Notwithstanding if the construction sector is less innovative than others, the desire for innovation in construction is well recognised (e.g. Atkin, 1999; Manseau and Seaden, 2001). Gann (2000: 220) comments that construction firms need to improve their capabilities in managing innovation if they are to ‘build reputations for technical excellence that set them apart from more traditional players’. Moreover, Sexton and Barrett (2003a: 613) remark that successful innovation enables construction firms to better satisfy ‘the aspirations and needs of society and clients, whilst improving their competitiveness in dynamic and abrasive markets’. Although the demand for innovation is unquestioned, research into innovation in the context of construction is sparse. Research into innovation in construction is not specific to the industry and still very much in its embryonic stage. Winch (1998: 272) echoes this view and suggests that more innovation research is required to ‘get a grip on the sources and applications of new ideas in the construction industry’.

In an effort to bring in a new ‘can innovate, should innovate, want to innovate’ construction industry culture, this book aims to address this research gap, aiming specifically to promote the benefits of innovation and stimulate innovation capability within and between small and medium sized construction firms who make up the majority of the industry. The results are drawn from case studies of innovation activity in seven small construction firms. The issues addressed include:

- the focus and outcome of innovation

- the organisational capabilities of innovation

- the context of innovation

- the process of innovation.

This chapter begins by setting the backdrop of the UK construction industry, around which this investigation is based, then leads on to define what a small and medium enterprise (SME) is and why innovation is imperative.

The UK construction industry

The construction industry is Europe’s largest industrial employer, representing 7.2 per cent of the continent’s total employment and 9.9 per cent gross domestic product (GDP) (FIEC (European Construction Industry Federation), 2003; see Table 1.1). In the UK, the industry employs 8 per cent of the workforce (Department of Trade and Industry (DTI), 2003a).

The construction industry is one of the most complex and dynamic industrial sectors. It relies heavily on skilled manual labour that is supported by an interconnected management and design input, which is often highly ‘fragmented’ right up to the point of delivery (Mohsini and Davidson, 1992). A large and complex project will involve many design, construction and supplier organisations, whose sporadic involvement will change throughout the course of the project (for example, see Carty, 1995). The organisations will be both large and small, and although they have usually never met before, they are expected to work together effectively and efficiently throughout the duration of the project. Complicating this situation yet further, the significant majority of design and construction activities are subcontracted, which renders collaborative and integrated working extremely problematic. In addition, design and construction practitioners typically find themselves working on several projects at the same time. According to Mullins’ (1999) generic and rather simplistic prescription, the success of a project relies heavily on having clearly defined objectives and well-defined tasks. But this is not always apparent in construction, as the client’s objectives often crystallise only over the course of the project.

Table 1.1 Number of construction employees and production by country

Table 1.2 illustrates the variety of disciplines and trades in the UK construction sector. The number of main trade organisations has fallen steadily from 84,885 organisations in 1992, to 54,043 in 2002 (DTI, 2003a). This equates to a 36.3 per cent decrease in main trade organisations compared to a 19.2 per cent decrease of the total number of organisations for the same period. Thus, the variety of specialised organisations prevails over that of their main trade counterparts. According to Pearce (2003), the variety and diversity of organisations in the construction sector is imperative due to the complex nature of the design and construction of modern buildings and facilities. Conversely, in comparison, the number of persons employed by the industry has risen by 9.9 per cent due to the rise in demand for construction work; in 1992 the industry employed 1,846,000 persons and in 2002 this figure rose to 2,029,000 (DTI, 2003a). Therefore, the inverse correlation between the number of organisations (particularly main trade) against the number of persons employed would suggest that smaller specialist organisations are foremost.

Table 1.2 Number of UK construction organisations by trade per year

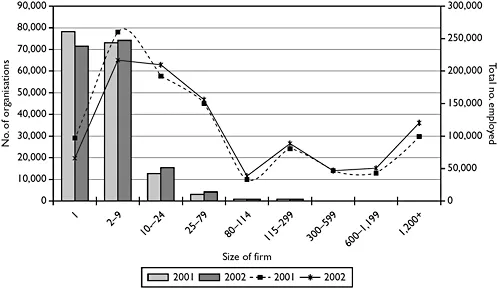

Thus, the majority of the construction labour market is self-employed (Briscoe et al., 2000). The scale of small organisation activity in the UK construction industry is considerable, with, in 2002, 99.3 per cent of UK construction organisations having between one and seventy-nine staff and employing 65.4 per cent of the total construction workforce (DTI, 2003a; see Figure 1.1). According to Storey (1998) and Smith and Whittaker (1998), there is no single, uniformly acceptable, definition of a small organisation that can be applied across all industrial sectors. Definitions that relate to ‘objective’ measures of size, such as the number of employees, sales turnover, profitability and net worth, are not comparable across all industries. In 1971, the Bolton Committee employed a discordant portfolio of different definitions of a small organisation according to the sector in which it operated (Bolton, 1971). Bolton defined a small organisation in the construction sector as having twenty-five or fewer employees, but this made international comparisons virtually impossible. Bolton’s statistical definition has not been agreed nor widely employed by construction researchers and economists. To overcome the divergence of categorisations, the European Commission (EC) coined the term ‘small and medium enterprise’. The SME sector is therefore taken to be enterprises – except agriculture, hunting, forestry and fishing which employ fewer than 249 workers – and is further disaggregated into three components (European Commission, 2003):

- micro enterprises: those with 0–9 employees

- small enterprises: those with 10–49 employees

- medium enterprises: those with 50–249 employees.

Although the EC’s definition of SMEs again has not been unequivocally implemented – in government-sponsored studies of UK Training and Enterprise Councils (TECs), five out of six reports defined SME as under 199 employees, and the sixth as under 250 employees (Whittaker et al., 1997) – it will be adopted throughout the course of this book.

The predominance of micro enterprises in the UK construction industry, employing between one and nine persons, over larger-sized organisations (see Figure 1.1) may be attributed to the fact that large contracts require specialist work and the specialist contractors are predominantly self-employed and, where necessary, employ a few additional hands (Abdel-Razek and McCaffer, 1987; Gale and Fellows, 1990). According to Langford and Male (1992), larger organisations generally resort to a greater use of subcontractors (micro and small enterprises) in a bid to reduce the overhead burden of tax, National Insurance contributions and working capital needs. This stance may contribute to the greater decline of the number of main trade organisations, as evidenced in Table 1.2. Thus, any overall performance improvement of the industry through innovation will be significantly influenced by SMEs, of various trades, as they make up the majority of the industry.

Figure 1.1 Number of UK construction organisations and employment figures in 2001 and 2002

Source: adapted from DTI, 2003a

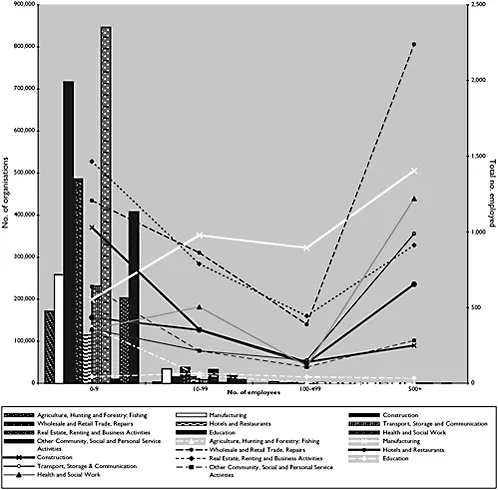

The predominance of SMEs in construction is not unique as is often thought. The agriculture, hunting, forestry and fishing sectors follow a similar pattern to that of construction (SME Statistics, 2002; see Figure 1.2). The manufacturing sector is seemingly a mirror to that of construction: more persons are employed in large enterprises than micro and small enterprises. Only the ‘wholesale and retail trade/repairs’ and ‘real estate, renting and business activities’ sectors are relatively balanced in terms of the number of employed in micro and large enterprises. However, only the construction industry, with the exception of manufacturing in some instances, operates within a project-based environment with temporary teams consisting of actors from various discipline backgrounds. The structure of the industry is arguably a function of the work it is called upon to do.

Why research innovation in SMEs?

Despite increasing interest in the small business in the UK, its importance in the economy is often still underestimated (Storey, 1998). According to Curran and Blackburn (2001), the primary reason for this is that there still remains a tendency to see small businesses as less central to economic activities than large businesses. Further, much of the research conducted so far has not been high quality due mainly to failures to recognise the special problems studying the small business poses for researchers. This book aims to address this research gap by viewing innovation in SMEs within the context of its wider role in the construction industry.

Figure 1.2 Number of UK enterprises and employment figures by industrial sector in 2001

Source: SME Statistics, 2002

The aspiration to enhance construction performance has been traditionally checked by the industry’s assumption that the intrinsic characteristics of construction and the construction industry – such as industry sector fragmentation, ‘boom-and-bust’ market cycles, use of relatively low technology and antagonistic procurement policies – inhibits innovation (for example, see Ball, 1988; Powell, 1995; Gann, 2000). Brouseau and Rallet (1995) capture much of this debate in their contention that institutional characteristics and the organisation and management of construction itself constrain innovation activity and restrict parties to apply innovations. Indeed, it has been argued that ‘the construction industry is infamous for the barriers it places in the way of innovation’ (CERF (Civil Engineering Research Foundation), 2000), and that ‘the desire for [construction] firms to change has come more from a fear of being left behind by competitors than from a belief in the benefits of innovation’ (Yisa et al., 1996: 49). Although it is acknowledged that construction firms have always demonstrated an ability to innovate (for example, see Slaughter, 1998), construction practitioners are now very much getting to grips with the need for, and management of, innovation as an explicit endeavour.

These objectives are linked to the assertion found in the general construction literature that innovation performance must improve, and more specifically from the research which investigated innovation in large construction firms. In the UK, public policy instruments to develop innovation in the construction industry have been categorised into programmes that support research and development; advanced practices and experimentation; performance and quality improvement; and taking up systems and procedures (CIB Task Group 35, 2000). Moreover, the relevance and accessibility of many of these initiatives for SMEs is debatable (Sexton et al., 1999).

Innovation theory and practice are being drawn from established bodies of innovation knowledge predominately based on other industries (for example, see Sexton and Barrett, 2003a), but they have not been sufficiently envisioned, embedded and evaluated in a construction context to form a robust body of construction innovation knowledge in its own right. Similarly, it is argued that ‘[construction] project-based, service-enhanced forms of enterprise are inadequately addressed in the innovation literature’ (Gann and Salter, 2000: 955). These observations are extended further by commenting that to our knowledge the construction innovation literature often emphasises construction firms of large size, and that innovation in small firms has been generally ignored.

We neglect small construction firms at our peril, as considerable evidence from the general innovation literature indicates that there is a significant difference in the innovation capability and output of small firms compared to large firms, with it being argued, for example, that small firms are organic in nature making them more agile and responsive, while large firms tend to be more mechanistic (for example, see Mansfield et al., 1971; Rothwell, 1989; Nooteboom, 1994; Rothwell and Dodgson, 1994). This difference needs to be understood, in order to underpin policy and corporate guidance. Drawing upon similar concerns in the design of technology transfer mechanisms for construction small to medium enterprises, it has been stressed that there is a

need to appreciate that construction SMEs and large construction companies are different animals, that live in different business market habitats, that must behave in different ways in order to adapt and succeed, and which need different sources and types of knowledge and technology to remain nourished and healthy.

(Sexton et al., 2006: 21)

Summary

This chapter has set the scene for the need for SME innovation research in the construction industry. The context of the industry was illustrated, and the predominance of SMEs in the sector was highlighte...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- List of illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Innovation demystified

- 3 Case study investigation

- 4 Focus and outcome of innovation

- 5 Organisational capabilities for innovation

- 6 Context of innovation

- 7 Process of innovation

- 8 The role of technology transfer in innovation within small construction firms

- 9 Conclusion

- References