1 Introduction

Bernd Rechel

In the last two decades, the protection of minorities has received unprecedented attention.1 For those countries hoping to join the European Union (EU), minority protection has become a key criterion in the accession process. But how has this political criterion been translated into practice? And what is the current state of minority rights in Central and Eastern Europe after EU accession?

While there is little doubt that the EU had in many cases a far-reaching impact on domestic policies and politics in accession countries, the initial enthusiasm is gradually giving way to a more sober reflection on where and when the EU really mattered (Haughton 2007). This is also the case in the area of minority protection, a policy area that has been largely ignored in the literature on EU accession. Furthermore, the contributors to this volume critically examine how far often declaratory policies or legislation have been implemented in practice, an issue often neglected in the minority rights literature. By providing a comprehensive assessment of minority rights in Central and Eastern Europe, covering all countries of the region that have joined the EU in 2004 and 2007 (Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, and Slovenia), this book aims to start filling these research gaps.

EU conditionality

Conditionality is a contested concept, in particular with regard to how it works and when it is effective. According to Schimmelfennig, conditionality was not a clear causal relationship, but rather a ‘reactive reinforcement’ (Schimmelfennig et al. 2002) of democratization. In similar vein, Hughes et al. (2004: 8) have argued that there is only a weak ‘clear-cut causal relationship between conditionality and policy or institutional outcomes’ (please see also the contribution of Gwendolyn Sasse in this volume).

A principal theoretical divide in discussion of conditionality runs between rational choice and constructivist approaches (Schimmelfennig 1999). According to a rational choice approach, actors are rational, goal-oriented and purposeful and conditionality only works when it brings benefits to national governments (Schimmelfennig et al. 2002: 36). A constructivist approach, on the other hand, emphasizes processes of persuasion and socialization and the sharing of norms and values (Börzel and Risse 2000; Vachudová 2005). A similar distinction is made in the literature on Europeanization, which differentiates between prescriptive and discursive modes of Europeanization (Faist and Ette 2007). In practice, these different forms of external influence were to some degree complementary. Moreover, socialization-based efforts of the Council of Europe and the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) were sometimes tied to EU accession, providing these organizations with additional leverage. In the area of minority rights, EU conditionality often motivated a change of policies, but the Council of Europe and the OSCE often shaped the substance of policy solutions (Kelley 2004a; 2004b).

The leverage of the EU on the domestic policies of candidate states can be usefully divided into ‘active’ and ‘passive’ leverage (Vachudová 2005). While ‘passive leverage’ results from the attraction of EU membership and is not linked to any deliberate policies of the EU, ‘active leverage’ results from the deliberate use of EU rules and conditionality (Vachudová 2005). The EU’s active leverage was mainly based on the political conditions of membership and the acquis communautaire, the body of EU legislation which candidate states were required to transpose into domestic law.

The most important step towards the EU’s political conditionality was taken at the European Council in Copenhagen in June 1993, which set out the ‘Copenhagen criteria’ for membership, which required, inter alia, ‘that the candidate country has achieved stability of institutions guaranteeing […] respect for and protection of minorities’ (EU 1993: 1). The political Copenhagen criteria for membership were of particular relevance for the protection of minorities, as this policy area was, until the 2000 Race Equality Directive, not covered by the acquis. The Copenhagen criterion of minority protection has been subsequently elaborated in the monitoring of candidate states. In July 1997, the European Commission published Agenda 2000, which included Opinions on membership applications. Beginning in 1998, the Commission published annual reports on the progress of candidate countries, which became one of the key instruments for monitoring progress towards accession. However, despite the continuing monitoring procedure, starting in 1999 all candidate countries were deemed to fulfil the political criteria of membership.

EU conditionality was further affected by the absence of a single EU policy template in the area of minority rights, as practices in EU member states vary widely. The ‘old’ EU member states France and Greece, for example, have not even recognized the existence of ethnic minorities on their territories. This meant that there were no ‘easily transferable models to emulate’ (Ram 2003: 48). Furthermore, many Roma in Western Europe face severe discrimination and racism, while Roma migrants from Central and Eastern Europe have often been turned away or even summarily deported to their countries of origin.

Assessing the impact of the EU

Assessing the impact of the EU faces problems of attribution. Both national governments and the EU have tended to overstate the impact of EU pressure. Furthermore, the demands of intergovernmental organizations have been conflated and it is at times difficult to ascertain whether a policy change was due to the influence of, for example, the EU, Council of Europe or the OSCE.

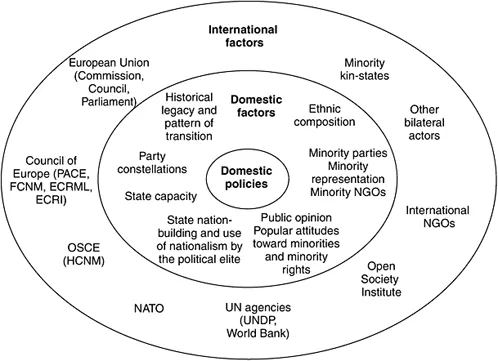

Furthermore, minority rights policies and politics are the result of a complex set of domestic and international factors. At the domestic level, these factors include the historical legacy and pattern of transition from communism, domestic political constellations, the process of state nation-building, state capacity, public attitudes towards minorities and minority rights, and the political organization and representation of minorities. At the international level, the conditionality, interest and pressure of Western organizations, and minority ‘kin-states’ and international non-governmental organizations (NGOs) have an impact on minority rights policies and politics in the region (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 shows in a schematic way the numerous and often interrelated factors that have an impact on domestic minority rights policies. The figure illustrates that international factors do not result directly in any domestic policy changes, but are mediated and filtered by domestic politics, which themselves can be influenced by international factors. As Jacoby observed, the ‘constraints of historical structures and conservative actors often deflected the reform course charted by elites’ (Jacoby 2004: 21). In a number of countries in Central and Eastern Europe, a change of the political party in power led to important improvements in minority rights. In other countries, in particular where ethnic nationalism gained prominence, such as in Romania and Slovakia, domestic politics acted as a brake on external influence on minority protection. Slovakia under the Mečiar government between 1994 and 1998 is an often-cited example in which domestic power considerations outweighed EU rewards, and Western conditionality had no major impact on governmental policies, although ultimately the opposition was strengthened by the increased international isolation of Mečiar’s regime.

Figure 1.1Factors influencing domestic minority rights policies.

Notes

ECRI: European Commission against Racism and Intolerance.

ECRML: European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages.

FENH: Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities.

HCNM: High Commissioner on National Minorities.

PACE: Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe.

UNDP: United Nations Development Programme.

Figure 1.1 further indicates that actors shaping minority policies are often not monolithic. Within the Council of Europe, for example, the Parliamentary Assembly, the monitoring mechanism of the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities (FCNM), the monitoring procedure of the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages, the European Commission against Racism and Intolerance, or the European Court of Human Rights sometimes send conflicting messages to EU candidate states. What is even more, some of these institutions may find the backing of the European Commission, while others may not. In the case of Bulgaria, for example, the European Commission ignored relevant court cases of the European Court of Human Rights, as well as the country reports of the European Commission against Racism and Intolerance. This may have contributed to the rather dismissive reaction of the Bulgarian authorities.

Finally, it has to be recognized it is not the actor positions themselves that are decisive, but rather the perceptions of these positions by others (Pettai 2006: 132). This social construction of actor positions is probably most apparent in the way that the actions of minority kin-states, such as Hungary and Russia, are perceived by countries with Hungarian or Russian minorities. The policies of minority kin-states may often appear to be more threatening than they are in reality. These processes of social construction also apply to the positions of Western organizations and further complicate the analysis of minority rights policies and EU conditionality.

The contributors to this volume recognize the complexities involved in analysing minority rights in Central and Eastern Europe. They attribute policy changes or inertia to a range of factors, of which accession to the EU is an important one, but one among many others.

Main results

Convergence

Over the last two decades, an array of policy and legislative initiatives related to minorities has been initiated in the countries of Central and Eastern Europe. It is possible to identify areas where there were converging trends, as well as areas in which there is strong variation across countries. A convergence in terms of minority protection can be observed in the adoption of anti-discrimination legislation, the ratification of the Council of Europe FCNM, the adoption of programmes for the integration of Roma, and the establishment of governmental bodies for minority issues. All of these policy changes can be directly related to pressure from the EU.

The impact of the EU on minority protection in candidate countries is perhaps most evident in the area of anti-discrimination legislation. Directives on non-discrimination were adopted in 2000 and candidate states were required to transpose them into national legislation. The Council Directive 2000/43, also referred to as ‘Race Directive’, ‘Racial Equality Directive’ or ‘Race Equality Directive’, prohibits direct and indirect discrimination on the grounds of race or ethnicity in the areas of employment, training, social protection, education, and access to public goods and services. The directive further provides for the reversal of the burden of proof on the alleged perpetrator and the establishment of enforcement bodies for the promotion of equal treatment (European Commission 2000a). All ten new EU member states from Central and Eastern Europe have made legislative changes to transpose this part of the acquis, although with varying degrees of speed and comprehensiveness.

Another point of convergence is that all ten countries have acceded to the FCNM. Instead of setting up its own standards in the area of minority rights, the EU has encouraged candidate countries to adopt the Framework Convention and to follow the recommendations of the OSCE High Commissioner on National Minorities, boosting the leverage of these two mechanisms for the protection of minorities. In contrast to the Framework Convention, the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages, which has not been promoted by the European Commission in the accession process, had, by the end of 2007, only been ratified by four of the ten new EU member states from Central and Eastern Europe. The Framework Convention has been described as the European Commission’s ‘primary instrument for translating the minority criterion into practice’ (Sasse 2005: 13). However, it seems that this criterion has not been consistently or strictly applied, as Latvia had not ratified the Convention by the time it became a member of the EU in 2004, but only acceded to the Convention in 2005.

Furthermore, all ten countries (except Estonia) have adopted programmes for the integration of the Roma minority. While it is somehow surprising for the countries with significant Roma populations that it took until the second half of the 1990s before they embarked on Roma-specific integration programmes, it is testament to the power of the EU to set the political agenda in the accession process, that even countries with very small Roma minorities (Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and Poland) have adopted Roma integration programmes. Despite these numerous initiatives, however, changes on the ground have remained remarkably limited.

Finally, all countries have established governmental bodies dealing with minority questions. This has helped to raise the political profile of minority issues, but these new institutions tended to remain consultative bodies without sufficient authority to implement minority programmes.

Divergence

In contrast to these points of convergence, trends with regard to positive minority rights are far less clear. A major reason for this variety is that the EU was not interested in minority rights per se. It paid particular attention to the socio-economic integration of the Roma minority, but this was an area that fell outside the scope of cultural or linguistic rights. Furthermore, a major weight of EU conditionality fell on the ‘technical’ requirement to adopt the 80,000 pages of the acquis (Grabbe 2003; Hughes et al. 2004: 25). As the European Commission itself noted, ‘incorporation of the acquis by the candidate States in their legislation, and adaptation of their capacity effectively to implement and enforce it, remain the key conditions for progressing in the negotiations’ (European Commission 2000b: 31–32). The acquis, however, has covered different policy areas to very different degrees (Jacoby 2004: 16–17). Although providing a detailed regulation of some policy areas, others, including the area of minority protection, have not been covered in any detail. The ‘thinness’ of the acquis in these areas resulted in a ‘conditionality gap’ (Hughes et al. 2004: 174) where acquis leverage was weak, increasing the scope of action for candidate countries (Hughes et al. 2004: 27). Where the acquis density was low, candidate states were ‘free to pick and choose (or ignore) prevailing Western models’ (Jacoby 2004: 16). In these p...