- 294 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Dubai: Behind an Urban Spectacle

About this book

Yasser Elsheshtawy explores Dubai's history from its beginnings as a small fishing village to its place on the world stage today, using historical narratives, travel descriptions, novels and fictional accounts by local writers to bring colour to his history of the city's urban development.

With the help of case studies and surveys this book explores the economic and political forces driving Dubai's urban growth, its changing urbanity and its place within the global city network. Uniquely, it looks beyond the glamour of Dubai's mega-projects, and provides an in-depth exploration of a select set of spaces which reveal the city's 'inner life'.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Dubai: Behind an Urban Spectacle by Yasser Elsheshtawy in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Urban Planning & Landscaping. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

The Emerging Urbanity of Dubai

‘... In that Empire, the craft of Cartography attained such Perfection that the Map of a Single province covered the space of an entire City, and the Map of the Empire itself an entire Province. In the course of Time, these Extensive maps were found somehow wanting, and so the College of Cartographers evolved a Map of the Empire that was of the same Scale as the Empire and that coincided with it point for point. Less attentive to the Study of Cartography, succeeding Generations came to judge a map of such Magnitude cumbersome, and, not without Irreverence, they abandoned it to the Rigours of sun and Rain. In the western Deserts, tattered Fragments of the Map are still to be found, Sheltering an occasional Beast or beggar; in the whole Nation, no other relic is left of the Discipline of Geography.’

‘Of Exactitude in Science’ from Travels of Praiseworthy Men (1658)

by J.A. Suarez Miranda (Borges, 1975)

by J.A. Suarez Miranda (Borges, 1975)

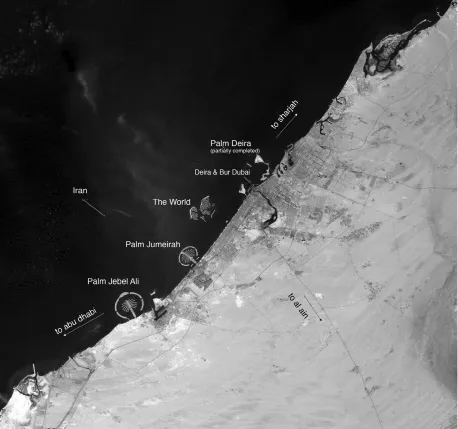

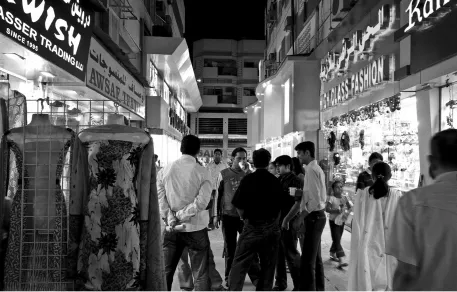

The above fantasy tale is cited when making a case that the representation takes on the dimensions of reality to the point of replacing it. French theorist Jean Baudrillard (1995) uses the story as a metaphor for his notion of the simulacrum; he suggests that it is the map that people live in, the simulation of reality, and it is reality that is crumbling away from disuse. One could argue that the city of Dubai is perhaps the ultimate realization of this vision. Our perception of the city is to a large degree shaped by representations in the media. Opinions are formed based on what is presented to us. Thus, Dubai is a city of islands shaped like palm trees, a sail-like hotel, Pharaonic temples used as shopping malls, and the list goes on (figure 1.1). This representation becomes in the mind of many a Borgesian reality – this is the true Dubai. Actual visits are merely used to confirm such views.1 But if one were to look beyond this seemingly naïve view of the city, a different picture emerges. Dubai is not merely composed of megaprojects; it certainly is not a fake or artificial city – observing its everyday life shows a place full of aspirations, struggles, and encounters taking place in all sorts of settings. It is also a unique, unprecedented urban experiment. No other city houses more than 200 nationalities, nor is there one whose native population represents less than 10 per cent of its residents. Such a situation has created a unique urban condition which cannot be explored by looking only at its spectacular projects and urban developments; one must move into its lesser known spaces, hidden in the alleyways and streets of Deira and Bur Dubai – its ‘traditional’ neighbourhoods from where the city originated and grew (figure 1.2). Here the true Dubai emerges which is not a representation or a fake reality. My aim in this book is to uncover and reveal these spaces, which I believe constitute the essence of the city and where its unique urban experiment is expressed spatially.

1.1. Satellite view of Dubai in 2006. (By courtesy of NASA)

1.2. The teeming alleyways of Meena Bazaar.

Aside from uncovering the real city, why should we be concerned with Dubai in the first place? It is not a great city – not in the sense that London, New York or Paris are great cities. These constitute our urban imaginary, the model that all those seeking global stature must aspire to. Their symbols of urbanity are a source of emulation all over the world – gleaming high-rises, quaint or ethnic neighbourhoods, and fancy restaurants. So, what lessons could possibly be learned from Dubai? To wit, the reasons – usually cited in this context – could be summarized as follows: it is an Arab success story, an example of successful urbanization that has eluded other parts of the region; it is also a good model for transnational urbanism, i.e. the degree to which, seemingly, it has been able to integrate various ethnic groups in a multi-cultural setting (labour camps notwithstanding). And it also has become a source of great influence in the region – to the extent that the so-called Dubai model became an actual term, connoting the exportability of its particular mode of development. I discuss these characteristics throughout the course of the book. They are debatable of course – some may not even be true – but they do constitute the reasons why there is such a fascination with the city.

One particularly potent argument is that there is, among many observers, a strong belief that the centre of power has shifted to the East. Moving away from the crumbling, perhaps even decaying, urban centres of the West, new centres are emerging. These can be found not only in China’s burgeoning urban conglomerates such as Shanghai, Shenzhen or Beijing, but also in Singapore, Hong Kong, Kuala Lumpur, Mumbai and, of course, Dubai.2 A passing visit through any of their newly-built airports shows a dramatic contrast to their European counterparts. Their newly-built city centres are shining examples of societies in transformation. Dubai is positioning itself as a gateway between these newly emerging centres of the East and the West, a ‘crucial staging post in the shift in economic power from the west to emerging Asia’.3 Its mode of urbanism is a response to this positioning. All of this illustrates the importance of examining developments taking place in Dubai, particularly in the light of the recent economic slowdown and the extent to which it has affected the city. This has shown the degree to which Dubai has become integrated in the global economic system – more than anywhere else in the region.

In this introductory chapter, I present the book’s scope and provide a summary of its chapters. I conclude by discussing the global financial crisis and its impact on the city of Dubai – leading some observers in the media, but also in academic circles,4 to proclaim the city’s demise. But, to parody Mark Twain, reports about Dubai’s death have been greatly exaggerated. In fact such views are expressed because the city is exclusively viewed through a Borgesian lens. Thus, this book is not just about the city’s megaprojects. I am going behind them – as implied in the title – digging deeper, uncovering Dubai’s multiple layers, in the process hoping to reveal a real city, whose urbanity has the potential to be a viable model for urbanism in the twenty-first century.

The Scope of the Book

It could be argued that Dubai’s transformation is unprecedented in the history of urban development – perhaps rivalled only by China. Its megaprojects have become a source of debate, argument and, most importantly, an influence throughout the region and the world. Dubai is a city attempting to become a global player, competing with cities in the Southeast Asian region, for example. Here comparisons are made with Hong Kong and Singapore among others. Conventional modes of discourse attempt to understand the ‘Dubai phenomenon’ by critiquing its fragmentation, polarization and quartering of urban space. Analogies are drawn to other world cities where such issues have been widely debated and cited as evidence for the drawbacks of globalization and its impact on urban form. Yet Dubai is quite unique in that it does not have a conventional historical core, or a conventional population make-up. Situated in the desert it is, seemingly, a tabula rasa allowing it to become a laboratory where various urban experiments are being carried out. Moreover its transient population, drawn from all over the world, has created a unique mix where the boundaries between local, Arab, and expatriate have been challenged. Its cultural landscape has seemingly blurred the distinctions of East/West, orient/occident, colonial/post-colonial, etc. Yet a closer examination reveals a movement towards segregation and fragmentation, a ‘post-urban’ centre resulting in a unique mix of urban spaces. All of this is accelerated and heightened by a perceived absence of a historical burden.

As noted, I am arguing that a new form of urbanity is emerging in Dubai. Fuelled by a unique adaptation of neoliberal economic policies, a series of urban spaces are created which cater for a wide range of social groups. In that same vein, its ‘traditional’ centres are transformed to cater for the forces of capital flow. Its urban form is moving away from the old concentric city model and is constituted as a series of decentralized neighbourhoods or fragments. My examination of the city’s urban development, which stretches back to the turn of the last century, is admittedly an ambitious task. I began this investigation with the following preliminary questions:

- What are the economic factors/policies driving this urban growth? To what extent do these policies relate to the globalization of the world economy, and the flow of capital?

- To what extent do these policies relate to the megaprojects and free zones spread throughout the city? How do these projects relate to global developments?

- Where is Dubai situated within the global network of cities?

- What are the various forms of urbanity emerging in the city? Are conventional notions of place, identity, history and heritage challenged and re-constituted to respond to local as well as global conditions?

- Aside from the city’s much cited mega-developments are there are any other settings that may offer lessons for urban growth and development?

In addressing these questions the book is grounded in a historical discourse, exploring the city’s origin from a small fishing village to its current state. Relying on historical narratives, travel writing, and archival media accounts, I attempt to visualize the city’s development, moving it from what is typically a factual and remote depiction. By looking, for example, at the descriptions of travellers, a subjective dimension can be added which will be a closer approximation of the city’s character and the extent to which changes have affected its citizens. In that same vein, I include my own personal experiences and encounters in the city to add another subjective reading – or layer – to the narrative.

Further, I draw on urban theory to understand the extent to which the city is an approximation of, or a deviation from, contemporary theoretical constructs. The global city construct is usually taken for granted as a starting point in assessing the city’s development. Yet it has been subjected to criticism on a historical basis (e.g. Abu-Lughod, 1995); others have argued that the notion of a global city may not be a very useful concept for all cities and that we need to establish differences rather than similarities between cities (e.g. Peter Smith, 2002; Ley, 2004). To understand the parameters of this debate, I provide a critical review of the literature starting with the origination of the global (or world) city concept, the notion of ‘space of flows’ – an abstract space through which global cities supposedly interact – and the outcome of a ‘splintered’ urban form (Friedmann and Wolff, 1982; Friedmann, 1986; Sassen, 2001; Castells, 2000; Graham and Marvin, 2001). The work of Michael Peter Smith, David Ley and others, who have subjected the ‘Global City’ construct to serious criticism, is reviewed and their approach employed as a basis for a critical examination of Dubai. I also use the writings of Guy Debord and his notion of the urban spectacle as being symptomatic of modern life, and Marc Augé’s argument that super-modern cities are characterized by non-places, to see whether these characterizations could be applied to Dubai (Debord, 1967, 1995; Augé, 1995). It is through such an analysis that I hope to overcome both the ‘hype’ of Dubai’s success and the ‘myth’ of its artificiality.

Existing Literature

While there is an overabundance of journalistic accounts, there is a dearth of academic studies dealing with the city’s urban development. Exceptions exist and they range from the mildly ironic – a piece titled ‘Let’s build a palm island’ by Mattias Jumeno (2004), to the descriptive – Roland Marchal’s (2005) examination of Dubai as a global city – and the critical, exemplified by the work of anthropologist Ahmed Kanna (2005), who looked at the utopian image of Dubai. The last is admittedly a rarity. There are some scholarly articles dealing with Dubai in the context of other world cities, for example Benton-Short’s et al. (2005) article on migrant cities. My chapter on Dubai in a book on Middle Eastern cities, provides a general overview of the city’s development, with a particular focus on two projects – the Palm Island and the Burj Al-Arab hotel. I have also written two chapters examining Dubai’s influence in the region (Elsheshtawy, 2006, 2009) and have examined the city’s retail landscape and its hidden spaces in two papers (Elsheshtawy, 2008a, 2008b).

There are no books on the city’s urban development with the exception of an excellent geographical analysis by Erhard Gabriel from the Ahrensburg Institute of Applied Economic Geography. Published in 1987 the book is of ‘historical’ value, given that since that time the city has changed rapidly. Other books on Dubai deal with it from an historical (Wilson, 1999; Kazim, 2000), political (Davidson, 2005, 2008), or economic perspective (Sampler and Eigner, 2003). A recently published book by political scientist Waleed Hazbun (2008) sheds light on the role of tourism in the regio...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Preface

- 1. The Emerging Urbanity of Dubai

- 2. Arab Cities and Globalization

- 3. The Other Dubai: A Photo Essay

- 4. The Illusive History of Dubai

- 5. The Transformation of Dubai or Towards the Age of Megastructures

- 6. Spectacular Architecture and Urbanism

- 7. The Spectacular and the Everyday: Dubai’s Retail Landscape

- 8. Transient City: Dubai’s Forgotten Urban Spaces

- 9. Global Dubai or Dubaization

- Bibliography