1 Tropical climate

1.1 Definition

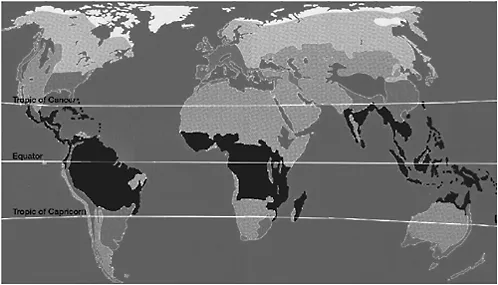

The climate is understood as the weather averaged over a long period of time, typically 30 years (recommended by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO)). The classification of the world climates relies on some climatic parameters, such as temperature and precipitation. As one of the most widely used climate classification systems, the Köppen climate classification divides the world climates into five major types: tropical climate, dry climate, temperate climate, continental climate and polar climate. It is interesting that the different climates are selected with close reference to native vegetation, which is the best reflection of local climate. Tropical climate, as reflected by its name, is the hot climate typical in the tropics. The general understanding is that the area within the Tropics of Cancer and Capricorn belongs to the tropical climatic zone (see Figure 1.1). However, latitude is not the only parameter which can govern the climatic boundary. Typical tropical climate can be found beyond 23°26′. The tropical climate is of very great importance. Occupying approximately 40 per cent of the land surface of the earth, the tropics are the home to almost half of the world’s population. Compared to the climate at mid-latitude, the tropical climate supports more lives and economic activities in the region. The four principal tropical areas include tropical Asia (India, Malaysia, Philippines, Indonesia, Singapore, northern Australia and so on), tropical Africa (the Congo Basin in West Africa, Mozambique, Angola and so on), tropical America (the Amazon Basin in Brazil, Argentina, Costa Rica and so on) and the tropical oceans and oceanic islands. But the climate is not uniform in the tropics. There are two broad climatic categories. One category is the warm and humid regions with excessive rainfall and considerable sunshine. It provides ideal growing conditions for luxuriant tropical plants and tropical rainforests. The other is hot and dry regions with extreme high temperature during daytime, little precipitation, low vapour pressure and low relative humidity. In these regions, deserts, semi-deserts, steppes and dry savannahs exist.

In this book, since we mainly talk about buildings and plants in dense built-up areas, we will concentrate on the hot and humid climate in which abundant tropical plants and large populations live.

Figure 1.1 Boundary of tropical climate (hot and humid) according to the Köppen climate classification. (Picture by Yu Chen)

1.2 Negative climatic impacts

It is believed that a building in the tropics means a confrontation in terms of construction and function with extreme climatic conditions (Lauber, 2005). It is easy to summarize the extreme impacts caused by the tropical climate through its climatic parameters as follows:

1.2.1 Temperature and relative humidity (RH)

The first and most straightforward negative impact of tropical climate is its relatively high temperature and relative humidity which may cause thermal discomfort and make the tempo of life slower in the region. The reason is that the combination of high temperature and high relative humidity will reduce the rate of evaporation of moisture from the human body, especially in the locations where the lack of air movement is experienced. Due to the continuous evaporation run by the sun’s heat and abundant precipitation, temperatures in the hot and humid tropics are seldom above human skin temperature during daytime. Heat loss at night, on the other hand, is limited by the abundant cloud cover. Therefore, night temperatures are maintained at a relatively high level. Such little variation of high temperature can continue throughout the year. To achieve thermal comfort, cooling strategies are always needed in built-up areas.

On the other hand, a humid microclimate condition may easily make condensation occur and lead to fungi/mould growth on building façades. Discolouration and damage of paint and coatings may take place. Health issues are also a concern in this condition.

1.2.2 Solar radiation

In general, solar radiation received in the tropics is very high. Although the region (between 15° to 35° latitude north and south) where the greatest amount of solar radiation is received is partially beyond the tropical climate, the equatorial region between 15° latitude north and 15° latitude south still receives the second highest amount of radiation. Furthermore, the proportion of diffused radiation is very high due to high humidity and the cloud cover in the region.

Excessive solar radiation can affect the thermal conditions of buildings in two principle ways. The direct way is through openings of buildings which may heat up the interior surfaces. Absorption by building façades and eventually transferred into interior space through conduction is the indirect way which can also increase heating effects indoors. Meanwhile, solar heat absorbed by buildings during the daytime and emitted in the form of longwave radiation at night is also a major concern in cities where the urban heat island (UHI) effect can be produced by such heat being emitted from densely placed buildings.

1.2.3 Precipitation

The amount of rainfall can be very high in hot and humid tropical areas although one or two dry seasons may be experienced. The major concern is to deal with surface runoff which may be extremely difficult in a densely built-up area. Adequate drainage from roofs and paved surfaces is of great importance. However, gutters, downpipes and other drainage systems in cities are not an economic solution for increasing water runoff. With rapid urbanization, the increase in paved surfaces becomes a heavy burden for the drainage systems in cities.

Heavy rain may also influence traffic flow and pedestrian movement. The concern when designing the openings of buildings is to avoid the negative impacts of driving rain and strong winds.

1.2.4 Wind

Wind can affect ventilation which is of great importance as a natural cooling strategy in the tropics. Weak or static air movement together with high temperature and relative humidity can easily cause thermal discomfort. It can be experienced during the inter-monsoon period or during the condition when wind-shadow is formed. Another concern is the direction of the prevailing wind and the orientation of buildings. In the tropics, eastern and western façades have been considered ‘unfavorable’ since high solar radiation strikes them during early morning and late evening. To minimize excessive heat gain from these orientations, it is recommended that long façades should avoid facing these directions. On the other hand, to enhance natural ventilation, long façades should be placed towards the direction of the local prevailing wind. Unfortunately, good solar orientation and good ventilation by the local prevailing wind do not always coincide. A compromise should be made to achieve a balance between the two.

1.3 Positive impacts

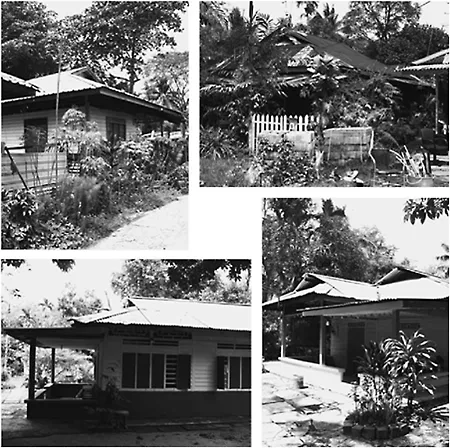

Because of minimal variation of diurnal and annual average air temperatures and relative humidity, architecture design in hot and humid conditions requires employment of cooling strategies to battle against heat. It means that buildings, their roofs, façades, systems and surrounding environment should all serve for the requirements of dissipating excessive heat. No heating consideration is necessary. The straightforward principles of thermal control are clearly reflected in tropical vernacular architectures (see Figure 1.2). It can be observed that the dominant characteristics of tropical buildings are openness and shading. The aim is to provide efficient ventilation and protection from the sun, rain and insects. The external walls are normally lightweight solid material (low heat capacity) with bright colour (low absorption and high reflectivity) yet ornamented beautifully. Roofs steeply sloped with an extensive overhang are also common to protect from heavy rain and hot sunshine. In some areas, the floors are elevated to keep them from the wet ground and to allow air circulation underneath. Overall, the buildings are very open in plan and construction and they are well shaded by surrounding plants.

Solar energy can be utilized in the tropics. Although there is a constant presence of cloud cover in hot and humid areas, a substantial amount of sunshine throughout the year is still experienced. This means that there is vast potential to tap into clean and renewable solar energy in the tropics, because of the following favourable conditions:

- high annual global solar radiation

- constant and uniform provision of sunshine throughout the year (no over- or under-provision occur seasonally)

- high diffused radiation which makes vertical collection possible.

Abundant rainfall, optimum temperature and sufficient sunshine make tropical plants grow extensively (see Figure 1.3). Without distinct seasons, the maintenance of plants is minimal compared to that in other climatic regions. Luxuriant plants can be found in rural areas, cities and the wilds. Greenery in a built environment can ameliorate the hot microclimate and create favourable thermal conditions for urban dwellers.

Figure 1.2 Existing ‘kampong’ houses in Singapore. (Photos by Yu Chen)

1.4 Thermal comfort

1.4.1 General definition

In 1966, the American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE) introduced a definition of thermal comfort for the first time: ‘Thermal comfort is the condition of mind that expresses satisfaction with the thermal environment.’ In order to acquire such a sensation of comfort, human body temperature has to be maintained at a constant level internally (about 98.6 °F/37 °C). The constant temperature is achieved by continuous heat exchange between the human body and its ambient environment. In general, a thermal balance can be reached by releasing excess metabolic heat from the human body to the environment. Occasionally, the

human body can experience a short-term heat gain although it does not last long. The heat exchange is completed through four principle ways: conduction, convection, long-wave radiation exchange and evaporation (see Figure 1.4). Fanger (1970) described the steady-state heat flow per unit area per unit time by the following equation:

where

| H | = | Internal heat production in the human body |

| Ed | ...