![]()

Part I

Exploration and the Production of Travel Pictures

![]()

1

The Framed View of Africa

TOWARDS THE UNKNOWN?

When a native of the temperate north first lands in the tropics, his feelings and emotions resemble in some respects those which the First Man may have had on his entrance into the Garden of Eden. He has set foot in a new world, another state of existence is before him; everything he sees, every sound that falls upon the ear, has all the freshness of novelty. The trees and plants are new, the flowers and the fruits, the beasts, the birds, and the insects are curious and strange; the very sky itself is new, glowing with colours, or sparkling with constellations, never seen in northern climes.1

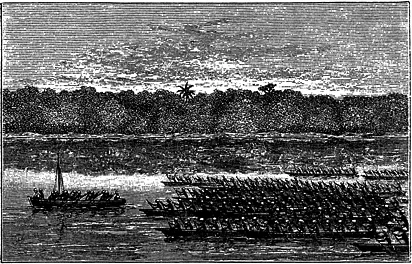

It is fascinating to imagine what it was like to be among the first European explorers in the interior of Africa. Travellers were inclined to emphasize the popular image of exploration, as the quotation from Narrative of an Expedition to the Zambesi (1865) by David and Charles Livingstone illustrates. They portrayed themselves as constantly encountering new countries, crossing nameless mountains and rivers and spending years never knowing what would confront them the next day.2 Printed illustrations also served to strengthen the image of lone, courageous white men endlessly facing new and unexpected situations and places during their journeys.3 An illustration in Henry M. Stanley’s Through the Dark Continent (1878), for example, shows Stanley steering a boat and the rest of the expeditionary crew Towards the Unknown, as the caption states (Figure 1.1).

The idea of exploration as a constant game played with the unknown was certainly alluring to the contemporary European public. Moreover, this notion has been repeated ever since in biographies and histories of travel.4 However, it would be untrue to state that the first travellers were entering a totally unfamiliar world. Even if vast areas of Africa remained unexplored by Europeans prior to Livingstone, Stanley and others, the European exploration of Africa should not be characterized as a constant march towards the unknown. Africa’s vicinity to Europe meant that plenty of information, rumours, legends and tales about Africa had reached Europe over the centuries.5 Much of this information was biased, misleading or completely incorrect; yet it still served to cement pre-existing presumptions about the continent and to prepare future travellers for its challenges.

Even more importantly, Africa was not as mysterious to those outside Europe. Omani Arab traders, allied with Indian merchants, financiers and local Swahili people had already “discovered” central Africa centuries before Europeans. Thus, numerous routes and commercial centres to the interior had been established.6 In spite of the difficulty of obtaining reliable maps, European explorers were able to benefit from earlier experiences of African travel and obtain first-hand knowledge about conditions in the interior. Moreover, local people—naturally the best authorities on the geography and terrain of the areas in which they lived—could be consulted or hired to guide the expeditions.7 Nineteenth-century explorers were also well equipped with compasses, sextants and other devices, which helped them to navigate with greater scientific precision. Thus, explorers had many means to orientate themselves in the unfamiliar interior of Africa and to prepare themselves for things to be encountered. Crucially, the obscurity of Africa was more a mental challenge than a practical problem.

This chapter aims to outline how explorers perceived and experienced Africa according to preconditioned notions acquired at home. Within the multidisciplinary study of travel, a great deal of attention has been paid to the importance of a sense of vision for modern travel experiences.8 Such an emphasis on sight has also justifiably been criticized as being oversimplistic.9 Yet, in aiming to understand and analyse the manner in which an unfamiliar region became visualized, sight is undoubtedly the most critical sense. Today, it is widely accepted that the eye has limitations as an instrument of perception and is highly selective in what it focuses on—there is far more to see than meets the eye. In the words of the art historian John Berger: “We only see what we look at. To look is an act of choice.”10 As a tool for visual perception, the eye focuses on sudden and unexpected elements in the middle of a stabile and predictable environment. Conversely, it seeks familiar and recognisable aspects in strange environments.11 Cultural aspects, such as values and beliefs of the surrounding society, are also widely believed to affect vision and observation. The prevailing idea of the strong connection between seeing and knowing was famously formulated in the first century AD by Pliny the Elder (c. 23–79):

Even within one cultural entity observation is fundamentally polyphonic and is affected by aspects such as age, gender, class, ethnic background, personal experience, expectations, beliefs, hopes and desires. In addition to being conditioned by knowledge, seeing is also affected by prevailing linguistic or visual conventions, which are employed in representing observations. Just as there is no vision without purpose, the literary critic W. J. T. Mitchell reminds us that the “world is already clothed in our systems of

representation”.13 In his classic text, Art and Illusion, the art historian E. H. Gombrich discusses the interplay between expectation and observation. He argues that our ability to observe and represent the world is inseparable from previous knowledge and expectations, on the one hand, and the available arsenal of verbal or visual means that can be used to interpret sights on the other hand.14 This leads to the idea of a hermeneutic circle of image, expectation and experience. It has been frequently demonstrated that in the context of modern tourism, existing pictures have a significant influence on behaviour and experience of travellers. They are crucial in shaping ideas and differentiating between alternative travel destinations. Although individual travellers may have no personal experience of the places they are going to visit, they set off on a trip with concrete and mental images of the destinations, which influence their perception and awareness. On arrival at the destination, they almost automatically start to search for the precise scenes they have seen at home and, once found, want to take a picture of them. Thus, old images become powerful tour guides and a visualizing measure.15 Peter D. Osborne crystallizes this trend by stating that much tourist photography actually reproduces the content of travel brochures, and is a process of confirmation, rather than discovery.16

The nineteenth-century exploration of Africa differed from modern tourism in that there was no great degree of prior knowledge or visual representations of the countries and the people that were being encountered. Nonetheless, each explorer carried with him an extensive intellectual baggage and a visual arsenal that served to direct his attention and filter reality. African explorers did not form a coherent group, despite their shared challenges, as each traveller had his own motives and sources of inspiration. No single theory or explanation is sufficient to encapsulate their role as observers. Whilst it is beyond the scope of this study to undertake an in-depth analysis of how an explorer’s perceptions were affected by his personality and individual preconditions,17 an attempt will now be made to identify some of the elements and aspects important in directing an explorer’s attention in Africa.

Four different approaches to conceptualizing Africa will be presented, each of which was prevalent in nineteenth-century European thinking about Africa and crucial for an explorer’s ability to understand and perceive the new environments and phenomena encountered: ideas of Africa as a continent to be commercially exploited, civilized, scientifically explained and enjoyed.

EXPLORERS AND THE IDEA OF AFRICA

The Concealed Potential

In legends, tropical Africa had long been associated with great riches, especially gold.18 In some regions, such as the Gold Coast in West Africa, gold continued to be the most attractive product for centuries. Another source of bounty also emerged, however, after Europeans established outposts along the coastal region of sub-Saharan Africa from the late fifteenth century onwards—namely, slaves. In the centuries that followed, millions of Africans were transported to the New World. However, in Enlightenment Europe, and in Britain in particular, criticism of slavery and the slave trade emerged. The abolition of the slave trade in British territories in 1807 and the emancipation of all slaves throughout the British Empire in 1833 were great victories for the anti-slavery movements both in Britain and elsewhere.19 It has been pointed out, however, that abolitionism accelerated the pace of empire-building by bringing about deeper involvement in African affairs. Initially, the motivation for legislation against slavery was economic to a large extent, resulting from the fear that it would harm domestic economy. Anti-slavery propaganda had painted a very rosy picture of the potential opportunities Africa could offer to compensate for losses caused by abolition. Instead of the need to enslave and transport Africans to American plantations, and then to ship products to European markets, it was planned that similar raw materials and products could be produced and sent straight from Africa.20 This idea became increasingly tempting in Europe, where industrialization had began to transform the traditional structure of societies. To ensure the competitiveness of national industries, new supplies of cheap raw materials and new markets for the flow of industrial products were urgently needed.

The African interior did not immediately appear very tempting to European commercial interests. The first white settlers on the west coasts of Africa had already, after all, tagged the continent as the “white man’s grave”. Tropical diseases, such as malaria and yellow fever, in tandem with intense heat and high humidity made living conditions extremely difficult for the...