1 Setting the stage

In the spring of 1945, with World War II winding down in the Pacific and Europe, the Communists began planning for postwar China. On April 23, 1945, two weeks before the surrender of Germany and more than three months before the surrender of Japan, the Chinese Communist Party convened the 7th Congress in Yan’an. Almost 20 years had passed since the previous Congress had assembled in Moscow in 1928. In the two intervening decades, the CCP not only had survived its darkest hour in its struggle against the GMD and Japan, but had emerged stronger. On the eve of the 7th National Congress, the CCP claimed a membership of 1.21 million.

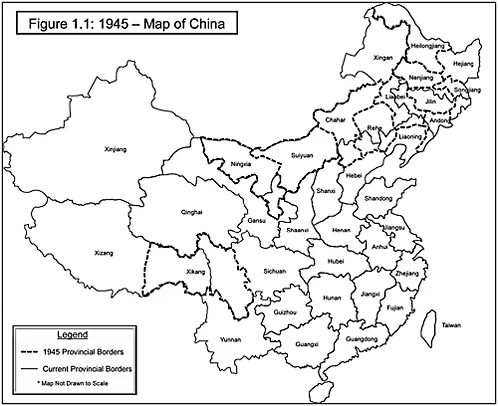

Figure 1.1 1945: Map of China.

Of this 547 regular and 208 non-voting delegates attended the Congress in Yan’an. The party had also created a standing, regular army of 910,000 men and a militia 2,200,000 strong. Although not yet tested in large-scale conventional operations, this so-called 18th Group Army consisted of experienced combat veterans well acquainted with accomplishing missions under great odds and with little modern equipment.

The 18th Group Army derived its name from the forced alliance between the GMD and the CCP, the Second United Front that formed to fight the Japanese. It consisted of the 8th Route Army and the New 4th Army.1 At its head was Zhu De, the most senior military commander in the Communist ranks. Zhu, in turn, reported to the CCP’s Central Military Committee (CMC), of which he was a part. The CMC was technically supposed to report to the GMD high command.2 However, it did not normally do so because of the remoteness of Yan’an and the poor relationship between Mao Zedong, chairman of the CCP and the CMC, and Chiang Kaishek, president of the GMD. Additionally, in the early days of 18th Group Army, its subordinate armies largely operated independently of each other. For instance, the 8th Route Army had the same commander and staff as the 18th Group Army, whereas a completely different set of personnel commanded the New 4th Army, which was located in another region altogether.

The reason for distinction was mainly due to the fact that the New 4th Army consisted of the collected remains of guerrilla units that had remained behind during the Long March and had continued to fight the GMD in south China.3 Following Yan’an’s guidance in 1937, these units formed the New 4th Army, entered into the Second United Front and turned their guns on the Japanese. Although their commander and political commissar were Communists, unlike the 8th Route Army the New 4th Army was directly under GMD command. This relationship turned sour in late 1941 during the so-called New 4th Army Incident, when Chiang’s forces destroyed the headquarters of the army. Most of the army escaped to north Jiangsu, falling back on its bases there and linking up with 8th Route Army units that had expanded east into Hebei and Shandong at the expense of the Japanese. In this way, the New 4th Army Incident proved a blessing in disguise. It allowed the New 4th Army to improve its strategic position and receive reinforcements and supplies from Yan’an.

The movements and development of the 8th Route and New 4th Armies went hand in hand with the creation of so-called Liberated Areas. Pockets of these Communist-administered regions were located in north China4 and encompassed a total population of 95,500,000 people.5 As a proto-state, the Liberated Areas represented more successful versions of the Jiangxi Soviet of the previous generation. Many of these had grown and prospered due to the lack of GMD and Japanese presence. As a result, most areas were located outside of the large cities and away from main railroads. These Liberated Areas demonstrated the CCP’s growing legitimacy and strength. They also added to the CCP’s military capability in terms of industry, logistics, intelligence, and easy access to labor. Territorial control also allowed the Communists to conduct social and political reform, winning them a great deal of support from the general populace.6

As CCP strength grew, the strategic situation by the spring of 1945 also looked promising for Yan’an. With solid bases in north China, the Communists were in a superior position to move into strategic areas occupied by the Japanese such as Manchuria and Shandong. History and tradition also favored the CCP; as “conquerors” from the north they were poised to join the ranks of Cao Cao and the Ming emperor Yongle. Only two men had ever unified China from the south. Unfortunately for the Communists, one of those was Chiang and he was prepared to do it all over again as soon as the war ended. The GMD army also had emerged from World War II larger and stronger. It was also well-trained and equipped, thanks to American assistance. Chiang could also call on his wartime alliances with the United States and Great Britain to provide air and naval transport. The international community recognized him as the only legitimate head of the Chinese state, which gave him the sole right to disarm and deal with the defeated Japanese armies and their allies. All these advantages would prove crucial in the postwar struggle. As for the CCP, only the Soviet Union recognized the Communists, although they had won a few supporters in the US thanks to the Dixie Mission. Unfortunately, Moscow also had a vested interested in keeping China divided and weak.

In light of these future challenges, the 7th Congress focused on improving their position vis-à-vis the GMD, not Japan, for the long run. Although they realized the war would soon be over, there was no call to begin mobilization for civil war nor were the Communists interested in speeding up Japan’s defeat. In one of his first speeches at the Congress, Mao laid out a broad outline for the defeat of Japan by “mobilizing the masses,” “expanding the people’s forces, and uniting all the forces of the nation under the CCP.”7 He envisioned seizing Japanese-occupied territory through coordinated armed uprisings from within while the 18th Army Group attacked from without. He also ordered the army to prepare for the defense of the existing Liberated Areas while continuing to expand and modernize. As for GMD-controlled areas, Mao determined the CCP would only conduct political work and, for the time being, permitted no military actions.8

Zhu De built on Mao’s speeches and went a step further. He declared “mobile” warfare should replace guerrilla warfare.9 “Mobile” warfare generally referred to using standing, conventional units to fight battles to destroy enemy units, not to capture, hold or defend territory. This pronouncement meant that the 7th Congress was one of the most significant events in the history of the PLA because it was marked the beginning of the end of guerrilla warfare. Zhu’s vision for defending the north China Liberated Areas was to conduct an interior line or “mobile” defense with large, professional units. This was a significant change from Mao’s earlier policy, which advocated guerrilla warfare as the primary option and “mobile” warfare as a secondary one. However, this did not necessary reflect an independent action on Zhu’s part because Mao would have had to approve such a significant change in strategy beforehand. Instead, the shift reflected the new political and military reality of having large amounts of territory and people to protect as well as now having an army capable of defending it. The party also would suffer a significant loss of prestige and public support if the Liberated Areas fell. Yet their strategy of choice illustrated the fact that the Communists anticipated having to give some ground due to the incomplete state of their military reforms and GMD strength. In the end, the survival of the army and the party was still paramount.

To prepare for the new mission, Zhu set a series of goals to modernize and professionalize the army that set the stage for the rest of the Third Chinese Civil War. The first task was a new training regime for the summer of 1945 that focused on improving tactics, leadership and maneuver.10 At the same time, Zhu oversaw a rapid increase of the army by reorganizing guerrilla elements into regular units. Zhu also tackled tough logistical issues such as the standardization of weapons and creating a domestic production base rather than relying on captured supplies.11 Driven by his past experience, one of the production items he most emphasized was artillery:12

In battles against enemy and puppet troops and troops of the diehard clique of the [GMD], our fighters often encounter pillboxes and temporary earthworks common in mobile warfare, which keep them from gaining victory.13

To this end, Zhu created an Artillery School in Yan’an to train new units. He also decreed that each full-strength regiment was to raise a mortar battery while understrength regiments were to form a mortar platoon.14

While Zhu prepared the 8th Route Army to defend the north China Liberated Areas, Mao had a different vision for south and central China. He dispatched some of his best regular units south to establish guerrilla bases behind enemy lines—the method by which the Communists had secured most of their existing territory. Earlier in October 1944, he had dispatched Wang Zhen’s Southern Detachment, a brigade-sized element from the 8th Route Army, along with Li Xiannian’s 5th Division from the New 4th Army to create guerrilla bases south of the Yangtze River.15 A month later, Mao ordered Su Yu’s New 4th Army 1st Division also to cross the Yangtze and create a base in Jiangsu and Zhejiang.16 They were able to do so because Japan was preoccupied with its Kohima and Ichigo campaigns in southeast Asia and in the GMD-occupied areas of south China, respectively. By March 1945, the Southern Detachment was across the Yangtze River establishing a base in north Hunan. In May 1945, after the 7th Congress, Li joined Wang to begin probing Hubei and Jiangxi.17 Communist guerrilla forces in Guangdong also began expanding northward to link up with these new bases.18

Carried out under the guise of continuing the war against Japan by “expanding Communist territory, reducing the occupied zones,” the true intent of Mao’s policy was to capture strategic areas before the GMD returned. As a directive from the Central Committee of the CCP stated, Communist forces in Henan were to occupy strategic points from which to prepare for a “GMD counterattack within a year or a year and a half.”19 In the 7th Congress, the Communists surmised that even if Chiang decided to counterattack, it would be another year before he could return to Guangzhou, much less north China—more than enough time for them to prepare defenses.20 The CCP also assumed that Japan would be unable to interfere. In fact, the Communists ordered their new guerrilla forces in south China to “mass its forces and seek battle with the Japanese no matter what the situation.”21 At the same time, the party high command believed the GMD would refrain from attacking out of fear of repeating the New 4th Army Incident and turning the war-weary populace against them.

In late July 1945, with the Pacific war in its final stages, Japanese forces began shortening their lines in China. This included abandoning hinterland possessions like Nanning and strengthening coastal areas, specifically the ports of Shandong. Instead of immediately moving into areas evacuated by the Japanese, Mao continued to stress the need for bases in the countryside, specifically where the four provinces of Hunan, Guangdong, Guangxi, and Jiangxi met.22 In August, only days before the Japanese surrender, Mao ordered Communist forces in the Central Plains23 to expand their rural bases into new areas such as the key mountainous regions of the Tongbai and Dabie Mountains.24 By fortifying these critical locations, the Communists believed they could prevent Chiang from controlling south China. In the event of civil war, he would first have to subdue these regions and would not be able to exert his full strength against the north China Liberated Area.25

The strategic developments in the spring and summer of 1945 thus illustrate a two-headed strategy. In north China, where the Communists had already established a mini-state in the midst of a skeletal Japanese occupation, the 8th and New 4th Armies prepared for conventional, defensive operations against the GMD. In south and central China, the CCP sought to create guerrilla bases which would divert GMD troops to the region and hinder, slow, and block Chiang’s process of unification. If the plan succeeded, the GMD would have to fight two wars simultaneously—a conventional one in the north and a counterinsurgency in the south. The Communists, however, made a serious miscalculation by assuming that the war against Japan would continue into 1946. The CCP was not the only party guilty of this mistake. The United States, for example, had made the same faulty assessment. Tokyo’s abrupt surrender inadvertently destroyed Yan’an’s carefully crafted plan to create these two separate fronts. In September 1945, the guerrilla bases in the south were not complete and neither the 8th Route nor New 4th Armies were ready for large-scale fighting. Events took on a frantic pace as Chiang began moving his legions forward. It was indeed a most inopportune moment to have to draft an entirely new strategy.

Cast of characters

As events and strategic plans unfolded from the 7th Congress to the end of World War II, it is important to note that the CCP and the 18th Group Army also underwent a series of organizational changes that significantly affected how the Communists would fight during the Third Chinese Civil War. In terms of personnel, the politicalmilitary elite who would go on to win the war and found the PRC emerged during the 7th Congress. Although the de facto party hierarchy had already mostly been settled, by electing a new Secretariat and CMC, the 7th Congress made it official. At the same time, the 18th Group Army also began to transform by dropping generic numeric designations and instead formed military districts which had jurisdiction over certain geographical regions. However, while there were no drastic additions or subtractions to the chain of command, the reorganization of the army did entail new promotions and responsibilities. The following section will thus discuss the Communist chain of command and the personalities therein.

Secretariat

The new Central Committee that emerged from the 7th Congress consisted of 44 members and 33 alternates. Approximately 50 percent of these men had military backgrounds. Day-to-day military and political decision-making for the CCP fell to the Secretariat, an elite group drawn from the upper echelon of the Central Committee. On June 19, during the 1st Plenary Session of the 7th National Congress, Mao was reaffirmed as both the Chairman of the CCP and the Secretariat. The other members of this key decision-making organ were vice chairmen Liu Shaoqi, Zhou Enlai, Zhu De, and Secretary Ren Bishi.

While Mao was the paramount leader of the party, he was not the most senior member of the Secretariat. Both Zhu De and Zhou Enlai arguably had more military experience and more impressive revolutionary pedigrees. However, neither had weathered the political infighting as well as Mao, nor they had been as prescient or opportunistic. Zhu’s lack of political power may be attributed to his desire to remain a professional soldier, a sentiment seen in his preference for conventional warfare even back to the days of the Jinggang Mountains. For instance, instead of attributing previous failures to “incorrect” political thought, he blamed them on the lack of a proper army and equipment. This proclivity was likely a result of his training as a youth, which included schooling at the Yunnan Military Academy and a stint with Cai Ao’s anti-Qing army in southwest China during the 1911 Revolution. After a decade of service with Cai, Zhu attempted to join the CCP but was rejected on the grounds that he was a warlord general. Zhu subsequently traveled to Germany to study military science at the University of Göttingen in 1922.

Zhu finally gained entrance into the CCP after meeting Zhou in Germany. He was expelled from Germany in 1925 after participating in protests, and he spent the next year in the Soviet Union receiving more formal military training. Upon his return, he became an officer in the GMD army and participated in the Northern Expedition. After Chiang’s betrayal of the CCP during the April 12 Incident in 1927, he participated in the Nanchang Uprising and co-founded the CCP’s first armed force, the predecessor of the PLA. After the GMD counterattack and the failure of the Communist operations in 1927, he eventually commanded the 4th Army with Mao in the Jinggang Mountains.

Despite the myths that arose around this particular partnership, the two rarely agreed on military strategy. While Zhu did recognize guerrilla warfare was the only real option, because of the weakness of the CCP vis-à-vis its enemies,26 Zhu still wante...