![]()

1

The national samples

Background and methods

Characteristics of the national samples

‘I am’: in love with the Hindi language, respectful to the national flag, respectful to the national anthem, respectful to my elders

(male, high school student, Delhi)

This chapter outlines the main elements of the research design: the survey methods used for securing samples, the questionnaire and its translation, and the gender vocabularies used to classify respondents’ comments. In the process, some characteristics of the national samples are introduced, thus setting the stage for a comparative examination of national feminisms in Chapters 2 and 3, illustrated with comments from my research samples. I say ‘illustrate’ because the national samples in all but two countries (Australia and Japan) are very small and my own deficient monolingualism meant relying on local researchers to translate the questionnaire, originally designed for a western study, and the comments made by respondents. My linguistic limitations are, to a small extent, compensated by a period of living in Beijing and Tokyo, where colleagues and students have acted as both friends and informants. With the exception of Indonesia, I have spent at least two research weeks in every other country in my sample, consulting with academic colleagues and presenting seminars on my findings. Furthermore, I know of no other comparative study exploring young people’s attitudes to feminism and gender issues in such a range of countries in Asia and North America. So, while the samples are neither representative of middle class youth in each nation nor comparable in terms of numerical results, the qualitative results explore the very different ways, as well as unexpected convergences, in how some urban middle class youth in each nation frame and consider issues of sexuality and feminism.

The ten countries chosen for analysis are a purposive sample: they represent the major nations in the world and the cultural and religious diversity of Asia, while also reflecting my own research interests and knowledge. Data for these ten countries are shown in Table A1.1 in Appendix 1, covering population, income, religious affiliation and some gender equity measures. The world’s four most populous countries are represented: China is still just ahead of India, with the USA and then Indonesia well behind (Troutner and Smith 2004:13; Lindsley 2004:223). The two largest economies are represented: the USA followed by Japan (with China rapidly gaining ground). Australia, Canada and the United States represent capitalist economies and western democracies, with Japan the major example of a mature capitalist democracy in Asia. India is the largest democracy in the world, while the Republic of Korea (hereafter South Korea) and Indonesia are more recent democracies. China, the largest communist country in the world, is represented along with a neighbouring communist country, Vietnam: both countries are well along the path to capitalist, if not democratic, reform.

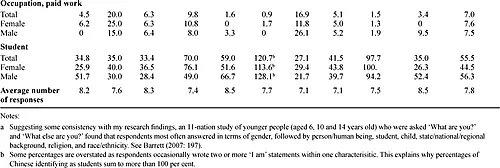

Some details of the sample are shown in Table A3.1 in Appendix 3. Because of funding constraints, only two samples are robust, the Australian and Japanese samples. While I collected many Australian samples myself, elsewhere I asked local researchers to locate a co-operative high school and university, surveying about an equal number of respondents in each, aiming for 50 to 60 respondents in total, and ensuring that at least half the respondents were female. I asked the local researchers to replicate the procedure I used—to survey students in a class specifically set aside for this purpose, with a researcher on hand to answer questions. Few of the local researchers achieved the exact sampling parameters I requested, although the Chinese, Canadian, Thai and South Korea samples are almost impeccable in this regard. By contrast, because of the ethics clearances required to gain access to almost any high school, the US sample is overweighted towards university students (90 per cent of the sample). At the other end of the scale, 84 per cent of the Australian sample are high school students. In two locations, local researchers recommended diversifying the sample beyond my two sources, to add a vocational college group in Thailand and a Hindi language college in Delhi. Given that my personal contacts were usually mandatory in securing entry into an Australian school, I allowed local researchers to choose the school, college or university which they surveyed. As a result, the Australian, US and Korean samples include some women’s studies students in the university classes. This is reflected in warm and knowledgeable comments concerning feminism from the female students and some highly charged emotional responses, pro and con, in the Korean male sample.

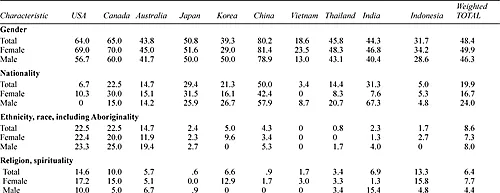

The questionnaire can be found in Appendix 2. The opening section asked respondents to complete the statement ‘I am…’ up to ten times; one such statement from the Indian sample is reproduced above. Although resistance or inability to think often statements did not vary much, ranging from an average of around 7 to 8.5 (see Table 1.1), there were significant national variations in the way young people met this task. The statement ‘I am’ has different resonances in different languages. For example, in Mandarin Wo shi calls for a noun rather than an adjective, the latter not requiring shi (‘am’). My local translator negotiated this situation by placing shi in brackets so that the statement read ‘Wo (shi)…’ Nevertheless, the linguistic difference might have contributed to the high percentage of categorical affiliations, so that the Chinese were the most likely of any sample to identify by nationality, their student status or gender (see Table 1.1): one Shanghai university respondent wrote ‘I am a boy’ ten times. Respondents in most of the samples were generally more likely to define themselves in terms of personality characteristics (for example ‘kind’ or ‘dumb’) or their skills and interests (‘a footballer’, ‘piano player’, ‘fan’ of Hindi film stars, wanting to travel overseas) rather than categorical affiliations (these are not shown in Table 1.1).

Religion

As will be seen in succeeding chapters, religion is a significant basis for respondents’ conservative attitudes to gender issues, particularly given the late twentieth century expansion of Christian, Muslim and Jewish fundamentalism, Hindu and Buddhist nationalism, and post-communist re-affirmations of religion such as the Falun Gong (Therborn 2004:73). The major world religions are represented in my sample: Islam, Christianity, Buddhism and Hinduism (see Table A1.1 in Appendix 1).

Thailand is ‘the world centre of Buddhism’ (Whittaker 2001:432), in fact, Theravada Buddhism (Limanonda 2000:249). Although women can become monks, Buddhism has been criticized for treating the female as an inferior life form: ‘It has been commonly believed that because of bad karma, especially if a man committed adultery, a man would be reborn a woman. And, if a monk committed adultery, he would have to relive 500 lives as women’ (Pongsapich 1997:14). Buddhism slightly outranks Shintoism in popularity in Japan (see Table A1.1 in Appendix 1). Indonesia is the world’s largest Muslim country, although Islam has never been declared the official state religion. President Suharto wished to deny religious leaders overmuch power (Suzanne Brenner 1996:676) and an ‘overwhelming majority’ of Indonesians desire their state to be secular (Bennett 2005:10). Islamization of the Indonesian region began in the fifteenth century BPE (Before the Present Era and equivalent to BC), advancing from west to east, so that there are more Hindus in Bali and Christians in Flores and West Timor. Localized forms of animism, Hinduism and Buddhism were hybridized with customary law (adat) to produce a ‘highly syncretic’ religious expression (Bennett 2005:9).

Out of its three centuries of colonial history, and a bloody dismemberment of the Indian sub-continent, the secular state of India emerged in 1947 as a predominantly Hindu state flanked by Pakistan on the east and west (predominantly Muslim, and which later became Pakistan and Bangladesh). In recent years, religious tension has again ratcheted up, possibly a response to the anxieties of growing income inequality consequent upon India’s entry into the global economy. Like the respondent quoted above, a number of Indians in my sample expressed their national pride in a religious register: ‘An Indian, A religious student, A defender of my country, An appreciator of the Hindi language’. This was particularly characteristic of the sample at the Hindu College in Delhi. By contrast, respondents in English language medium institutions in Mumbai cited their English language skills almost as frequently as their Hindi language skills.

Under communism in China and Vietnam, religion was regarded as a sign of

Table 1.1 Categories of affiliation in ‘I am’ statements, by gender and national samplea (responses as percentage of respondentsb)

backwardness (as it also was in India under prime ministers Jawaharlal Nehru and his daughter Indira Gandhi) (Vervoorn 2002:46). A survey of young people hanging out in shopping malls found that religion was important to 76 per cent of the US sample but only 21 per cent of the Chinese sample, although the Chinese youth did not know ‘what they believe in’ (Lindstrom and Seybold 2004:74, 87). China is the most secular of the nations in this study. However, in Vietnam only a third of the population declare no religion, and Buddhism is the major religion. Although Confucianism influences gender issues in China, its impact is more pronounced in Korea, where half the population declare they have no religion, and half each of the remainder are Buddhist and Christian.

Among Christian nations, the USA is often cited as peculiarly religious whereas Australia is described as a largely secular nation: ‘By and large… Australians regard religious passion as something that other people have’ (Maddox 2001:70). A survey conducted by the University of Minnesota found that US people distrusted atheists ‘more than any other minority group, including homosexuals, recent immigrants or Muslims’ (MacAskill 2007:8). Surveys conducted in the 1990s confirm US people as more religious in terms of belief in God, belief in the devil and weekly church attendance.1 Helen Hardacre (2005:242) notes that ‘The Shinto world appears small from one perspective: there are about 80,000 shrines in Japan, but only one in 10 of them has a full-time priest’. However, Jinja Honch (Association of Shinto Shrines) has strong connections with the Liberal Democratic Party, the dominant political party in Japan, and is a key player in the contemporary backlash against gender-equal legislative machinery and women’s changing work and family roles (Hardacre 2005:241). In Australia, similarly, a Christian faction has close alliances with members of the Liberal-National Party coalition, exercising disproportionate influence (in relation to the number of practising Christians in the community) on ‘family values’ and policies promoting the ideal ‘single-breadwinner, nuclear family model of domestic life’ (Maddox 2001:287). One mechanism by which this is achieved is to disguise ‘Christian values’ as Australian ‘tradition’ which is then ‘related to nationalism, civic order and public safety’ (Maddox 2005:2). This elision of patriotism and religion is not dissimilar to the way Hinduism in India is aligned with nationalism. Reflecting the comparative degree of religiosity, the USA and Indonesian samples are the most religious of my samples (see Table 1.1:14.6 per cent and 13.3 per cent of respondents, respectively, use this category of affiliation in their ‘I am’ statements, by contrast with 6.4 per cent of the weighted total). Religion is a marker of internal difference in the USA, respondents generally identifying as ‘Christian’ or ‘Jewish’ (although one was ‘Jewish and Christian’ and another was a ‘New Age’ adherent). In Muslim Indonesia, by contrast, respondents merely asserted that they were ‘religious’.

National identity and patriotism

Whereas females were more likely to claim religious adherence (7.7 per cent compared with 4.4 per cent of the weighted sample), the males on average were more likely to identify by nationality or express patriotic affiliation (19.9 per cent com-pared with 16.7 per cent of the weighted sample but a pattern of my Asian samples more so than the Anglophone samples), a characteristic also of Melanie Bush’s (2004:112) New York university sample and a cross-national survey of school children (Barrett 2007:102). The conservative religious cast given to patriotism pos...