1 Editors’ introduction

Patterns and dynamics of Asia’s growing share of FDI

Philippe Gugler and Julien Chaisse

Introduction

Capital throughout the world has become increasingly mobile in recent decades and international trade has been exploding. Advances in information communications technology and the accelerated pace of international distribution in recent years have promoted the growth of foreign investment which divides the various processes of research and development (R&D), procurement, production, manufacturing and sales, among others, between a number of countries. Until the recent past, foreign direct investment (FDI) and trade mainly flowed from the developed countries into the developed countries: in particular, the ‘triad’ (the European Union, the United States, and Japan). Until the mid-1980s, the role of developing and transitional Asian economies as sources of investment was negligible.

A regional pattern of FDI flows has emerged, with investors’ attention shifting away from traditionally important locations in developed countries in favour of emerging markets (Sauvant, 2005), especially Asia and South-eastern Europe. A survey by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) found prospects for Asia and the Pacific to be most positive, with over 85 per cent of experts, multinational corporations and investment promotion agencies expecting significantly increased FDI flows to the region (UNCTAD Investment Brief 2007).

As a result, more bilateral investment treaties (BITs) and double taxation treaties (DTTs) are now in force between developing countries than between developed and developing countries. Asia has, in fact, been the most active developing region in terms of concluding preferential trade and investment agreements (PTIAs). Asia concluded 38 per cent of a total of 14 PTIAs in 2005, followed by Latin America with a quarter of that percentage share.

FDI flows have increased dramatically in recent decades and continue to be a driving factor of economic globalization. As a centre for growth in the world economy, large parts of Asia have become a particularly attractive place for market-seeking FDI. It is in Asia that many of the recent and most innovative agreements have been signed and for which a detailed analysis of preferential commitments is available (Fink and Molinuevo 2008). In numerous Asian countries FDI restrictions have been reduced, leading to accelerated technological exchange and globally integrated production and marketing networks. Overall, this has benefited the emerging countries that have opened their doors to FDI.

According to the World Investment Report 2007, global FDI inflows rose in 2006 for the third consecutive year (UNCTAD 2007). This growth was shared by countries in various stages of development. FDI inflows to South, East and Southeast Asia maintained their upward trend last year, rising by 19 per cent to reach a new high of US$200 billion, according to UNCTAD’s annual report on global investment trends. South and Southeast Asia saw a sustainable increase in FDI flows, while growth in East Asia was slower. However, FDI in East Asia is shifting towards more knowledge-intensive and high value-added activities.

China and Hong Kong currently top the list of recipients of the largest amounts of FDI, absorbing approximately half of the total FDI inflow into Asia in recent years. China and Hong Kong are followed by Singapore and India, according to the World Investment Report 2007. Inflows to China fell by 4 per cent to US$69 billion last year, dropping for the first time in seven years due mainly to declining investments in financial services. Hong Kong attracted FDI worth US$43 billion, Singapore US$24 billion and India US$17 billion, which was equivalent to India’s inflows for the preceding three years added together. Meanwhile, FDI inflows to Thailand rose by 9 per cent in 2006, reaching a record of US$10 billion and consolidating the country’s position as the second-largest FDI recipient in Southeast Asia.

FDI in the service sector in the region was considerably increased but FDI related to mergers and acquisitions in manufacturing dropped. The report predicts that rapid economic growth in this region should continue to attract FDI to its countries in the coming year. In the first half of 2008, the value of cross-border merger and acquisition deals in the region rose nearly 20 per cent compared to 2007. FDI outflows from the region are also expected to increase. The report also showed that rising demand for oil and gas and metals, particularly from Asia, has spurred a boom in FDI in mineral exploration and extraction industries. These industries largely account for the recent increases in FDI in many mineral-rich developing countries, notably in Africa.

A large share of the FDI inflows into Asia originated from other Asian countries. Of the US$138 billion of FDI inflows into South, East and Southeast Asia in 2004, approximately 40 per cent is estimated to have originated from other Asian countries. China, Hong Kong, Indonesia, the Philippines and Thailand stand out as having inward FDI that is dominated by Asian investors.

Numerous factors have driven the increasing levels of intra-Asian FDI. Examples include:

- Competitiveness: A large component of international competitiveness for Asian firms is achieved through intra-regional sales within the home region (Rugman and Hoon Oh, 2008). International competitiveness should not be confused with globalization. Asian firms do not compete globally; instead, they mainly operate regionally.

- Need for global presence: Multinational enterprises (MNEs) are undergoing an attitudinal change, realizing that they operate in a global economy in which Asia is a rising force. In addition, developing country MNEs are investing in other countries to reduce the risk of overdependence on the home market. Offshore centres of excellence, such as India’s data recovery centres in Singapore, are examples of this trend.

- Costs of production: Labour costs are of concern to most MNEs, especially those from more developed nations. Production has increasingly been relocated to developing economies where costs are lower. This practice is commonplace in industries such as electrical and electronics, and garments and textiles – FDI in the electrical and electronics industry is strongly regionally focused while FDI in the garments industry is more geographically dispersed.

- Market access: Production and distribution centres are in due course set up close to consumer markets. This reduces the problems of transportation of perishable goods such as agricultural food products and processed food. The Indonesian-owned Indofood Corporation, for instance, has located production in China where a large part of its market resides.

- Favourable FDI regulatory trends in Asian host countries: Changes in government policy have facilitated FDI through creating greater openness to foreign investors, reducing taxes, simplifying procedures and enhancing incentives. In host economies, liberalization policies have created many investment opportunities, such as the privatization of state-owned enterprises and assets. As competition for FDI intensifies, countries are becoming more proactive in their investment promotion efforts. Dedicated bodies such as the investment promotion agencies are being established to attract FDI. The investment promotion agencies now consider developing Asia as a key FDI source region.

This volume focuses on the theme of the Annual Conference of the National Centre of Competence in Research (NCCR) Trade Regulation, which took place at the National Institute of Development Administration (NIDA) in Bangkok in January 2008. The theme of the conference was Expansion of FDI in Asia: Strategic and policy challenges. All contributions to this book (with one exception) are based on the papers and keynote addresses presented during the conference. The multidisciplinary approach provides an opportunity to explore the trends of recent FDI in Asia and their effects on multilateral regulation of FDI. The aim is to offer a review of the increasing attraction of FDI and the rise of Asian multinational enterprises from an economic perspective. A second objective is to add a political and legal analysis of these developments, in particular the changes in regulation of bilateral and regional FDI and the lessons that can be learned for international investment agreements (IIAs) and the constitution of trading blocs.

The book comprises three parts to investigate the current scenario in Asia. The first part addresses the internationalization strategy of emerging Asian firms with examples from China and India. The second part relates to the national and regional initiatives affecting trade and investment in Asia. The third part focuses on the Asian interest in multilateral rules on trade and investment. It raises the question of a potential new paradigm. We outline below the background against which the different chapters are set.

Table 1.1 Outward FDI stocks as percentage of GDP

Internationalization strategy of emerging Asian firms: examples from China and India

The share in the total stock of FDI deriving from developing and transition economies stood at 23 per cent in 1980. It had increased to 46 per cent by 1990 and to 62 percent in 2005 (UNCTAD 2007). Focusing primarily on the outbound side of Asian FDI, the book analyses the geographical and sectoral trends involved. Further, it looks at the key players in these FDI activities that have become the Asian MNEs. In understanding why their number has multiplied during the past decade, a number of salient characteristics should be explored to answer the question: What are the location and types of investments from Asian MNEs (financial services, high-tech industries, geographical interests and so on)?

Traditionally, the main Asian source countries for FDI have been Japan, Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong and Singapore. However, in recent years, the developing countries of Asia have begun to pull their weight (Tables 1.1 and 1.2).

China and India, for instance, are two giants on the move towards securing a greater share of energy assets overseas. Their strategy for controlling oil and natural gas reserves has led to rising FDI outflows. The China National Oil Company, for instance, has made major investments in the offshore oil and gas industry in Indonesia. The rapid development of China and India, the most populous countries in the world, has attracted the attention of international policymakers and industry leaders and should be given a particular place in this book.

China and India together account for about 37.5 per cent of the world population and 6.4 per cent of the value of world output and income at current prices and exchange rates.1 As the two countries play an increasingly weighty role in the world economy, their expansion is having a noticeable impact on global growth, through a number of channels, with trade, arguably, being the strongest and most direct (World Bank Development Indicators 2007).

Table 1.2 Outward FDI flows as percentage of GDP

China’s and India’s foreign trade patterns are largely dissimilar and have always been so (Winters and Yusuf 2007). In the case of China, using its vast resources of cheap labour and domestic savings to initiate building of infrastructure and inviting large amounts of FDI to spur the development of the manufacturing industry in the coastal areas has been seen as one of the initial and leading drivers for the country’s economic success. India’s strength, on the other hand, is based on its knowledge-based sectors such as IT and pharmaceuticals, its more developed financial markets and a more robust private sector.

FDI is an area in which India appears to lag behind China. In 2006, China attracted ten times more FDI than India. This is because China’s policies for foreign investors are more liberalized than those of India. Moreover, the Chinese economy is growing faster and the infrastructure is better. FDI in China has been increasing and this is not surprising bearing in mind the sheer size of the market and the opportunities for resource exploitation. In addition, the open-market policies pursued by China over the last two decades and the concerted efforts made to attract FDI have spurred FDI growth and a consequent interest in scientific analysis. The further economic development of China depends to a large extent on continuous FDI and policy-making that will facilitate inward investment. Moreover, foreign investment and development of specific industrial sectors are essential for establishing the infrastructure and superstructure of a modern market economy. The manufacturing and technology sectors form a core for production and productivity. In addition, there must be facilitation of trade and transport of manufactured goods and information processing. China’s entry into the World Trade Organization (WTO) suggests that trade will play an important role in the country’s economic development.

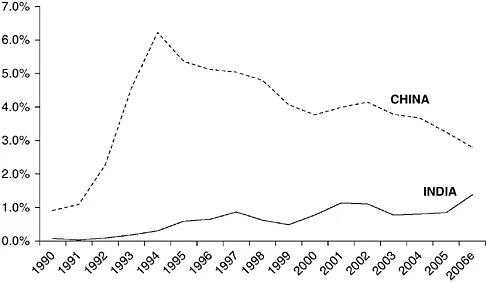

Figure 1.1 FDI in China and India, as a percentage of GDP

Source: UNCTAD FDI database.

Although strict protection policies remain in place in China in selected sectors such as the motor industry, India’s restrictive labour laws and limits affecting foreign shares in ownership restrain foreign investment in general. In particular, India’s inadequate infrastructure development makes it very difficult for multinational companies to ship products in and out of the country, and even within the country.

China is certainly a star performer in attracting FDI, but India did not perform as badly as expected in comparison to China. China accounts for 5 per cent of world GDP and India about 2 per cent, at current exchange rates (World Bank 2007). Development Indicators as bigger economies normally attract more investment, China currently tends to be the preferred destination of the foreign investors. But in terms of FDI’s percentage in GDP, China’s figure is less remarkable – little more than twice that of India (Figure 1.1).

Within South Asia, India is by far the leading host country for FDI. It received around US$19.4 billion in the fiscal year 2006, or about 80 per cent of total regional FDI (Table 1.3). India’s dominance in FDI in South Asia is largely due to the size of its economy, the largest in the region. However, India’s policy reforms geared towards liberalization also played an important part in India’s dominance of FDI. After its independence in 1947, India adopted a socialist planned economy. Inefficiency was a problem in all sectors, making it a high-cost economy. Regulations on imports and FDI were strict, and the domestic market was virtually closed for the next 40 years.

In the late l980s, however, the Indian Government gradually liberalized the economy and lifted restrictions on FDI. Consequently, India achieved high economic growth in 1988 and 1989. In July 1991, the New Industrial Policy was announced. Under this policy, foreign investment was approved without conditions, formalities for granting import licences were simplified, and private companies were permitted to enter fields that had previously been dominated by government-owned companies. India changed itself from a closed economy to an open economy. Movement towards liberalization in terms of FDI promotion is now common to all countries in South Asia.

Table 1.3 Net FDI inflows for South Asian countries (2005–2006)

In terms of business environment, the World Bank ranks China in the top 100 while India is not listed. But in some areas such as starting a business, obtaining credit, protecting investors and paying taxes, India still leads China.

The World Bank reported that South Asia is the second-least business-friendly region in the world, after Sub-Saharan Africa, based on its ‘Doing Business’ 2007 survey of the perceptions of foreign investors of 178 countries (World Bank Group 2007). India, the largest economy in South Asia, ranked relatively low, at 120, but this was an improvement over its 2007 ranking of 132. Only India and Bhutan could boast of slight improvements in their global rankings in 2008, suggesting an improving business climate in those countries. Conversely, the global rankings of the remaining South Asian countries deteriorated in 2008, indicating a worsening business environment in those countries. These deteriorating rankings are considered to result from foreign investor perceptions of poor infrastructure, restrictive labour policy and labour unrest, political uncertainties and civil conflicts, weak regulatory systems, and rampant corruption. Political instability and civil conflicts have been found to be a major factor in reducing the attractiveness of South Asia as a host for foreign capital. Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka continue to face political uncertainties and security challenges that are likely to hinder FDI. Empirical evidence demonstrates that FDI inflows into Sri Lanka are vulnerable to the ongoing civil conflict there. Likewise, in Afghanistan, the pace of foreign investment may be slow because of the sporadic suicide bombings, kidnappings and attacks. Political instability is also a major drawback for foreign investment in Nepal, while the worsening political situation in Pakistan (particularly in late 2007) may hamper FDI inflows into that country.

It may have been assumed that OECD countries took the lead in investing in China, but actually OECD countries only started to look at China from 2002 onwards. A large proportion of FDI into China comes from its diasporas abroad, from Hong Kong and Taiwan and f...