Introduction

Barely a mile away from the runway of Shanghai’s Hongqiao Airport in the Minhang District, a huge tract of suburban housing estate dominates what was formerly an 800 mu (over 50 hectares) plot of paddy-field. Comprising a mix of high-rise apartments, townhouses and villas, the privately developed and owned housing estate known locally as ‘Vanke Garden City’ is arguably Shanghai’s first large-scale ‘middle-class’ housing enclave built by Vanke Property Development, one of China’s most prestigious housing developers.1 Notwithstanding its location near a noisy airport, Vanke Garden City has, over the years, proven to be immensely popular with ‘new middle-class’ home-buyers and is widely regarded as an icon representing the dawn of Shanghai’s modern commercial housing development in the 1990s. Surrounded by 2-metre-high wrought-iron gates and concrete walls around its perimeter, the suburban private housing enclave comes equipped with high-tech surveillance technologies and is guarded round-theclock and patrolled by more than 280 privately employed security guards on site. A prominent sign erected outside the main entrance announces in bold Chinese characters that the premises belong to a private community and non-residents are not allowed to enter. Another sign at the front gate further proclaims that the gated commodity housing enclave belongs to a select group of ‘Model Civilized Residential Quarters’ (shifan wenming xiaoqu) that have been hand-picked by local district officials as exemplary of a ‘civilized’ modern living environment. Within the enclave, all housing clusters have electronic gated access and residents pay a monthly maintenance fee to enjoy condominium facilities such as swimming pool, club house, tennis courts, spas, landscape gardens and, all in all, a ‘new lifestyle’ (xinshenghuo fangshi) for those who can afford the escalating prices of commercial housing in Shanghai. In Vanke Garden City, commercial house prices have more than doubled over the past years, with prices now ranging from 800,000 yuan to over 3 million yuan.2

As one enters the gated neighbourhood, security personnel wearing crisp military uniforms can be seen prominently standing guard at street corners and road intersections, directing traffic while eagerly keeping on eye out for trespassers. The interior of the estate is further adorned with well-manicured garden landscaping, brightly lit pavements and meticulously clean pavements that are a far cry from the congested and dirty streets outside. Trash bins and manhole covers within the gated estate are all emblazoned with the conspicuous corporate logo of Vanke’s developer. Along the pavements, sounds of birds chirping and children laughing are emitted from tape recorders hidden under shrubs and tress. Overall, every minute detail and sensory pleasure in the neighbourhood has been meticulously planned and orchestrated to create a picturesque and pristine living environment —the hallmarks of what Vanke Corporation calls a ‘new concept housing’ (xinzhuzai linian) and ‘new housing movement’ (xinzhuzai yundong) that are aimed at promoting a new elegant and modern lifestyle (youya xiandai shenghuo fangshi) tailored to the desires and aspirations of the 16,000 ‘new middle-class’ residents and some expatriates residing within.

On first impression, these newly constructed residential estates (xinjian zhuzai xiaoqu) in Shanghai seem to resemble the California-style ‘gated communities’ found throughout North American cities and elsewhere (see Blakely and Snyder, 1997; Webster et al. 2002; Low, 2003; Glasze et al., 2006). Like many of the middleclass gated enclaves in Asia and Southeast Asian cities (see Connell, 1999; Leisch, 2002; Dick and Rimmer, 2003; Waibel, 2006), these affluent residential enclaves in Shanghai are planned as self-contained ‘mini-cities’ that display a distinct form of class territoriality with clearly marked out spatial boundaries and zones that are zealously guarded and fortified by high walls, fences, surveillance technologies and private guards. The houses in these gated communities are further designed in a bewildering and eclectic mix of styles combining European classical traditions, baroque, Spanish revival and a pastiche of modernist and post-modernist architectural motifs that are often out of synch with the surrounding environment.

Intrigued by the development of these private housing estates, I approached several local scholars and friends to find out more about these fengbi xiaoqu (literally meaning enclosed or sealed residential estate). Then, a well-meaning colleague with extensive fieldwork experiences in Shanghai cautioned that the ‘gated community phenomenon’ is more a ‘Western academic preoccupation’ that may not resonate well with the pressing housing concerns of local residents and even academic researchers in China. Although I too was wary of uncritically importing ‘Western’ urban theories and debates without paying adequate attention to the particular conditions and local realities in China, a quick internet search on the term fengbi xiaoqu revealed hundreds of entries related to the topic posted by Chinese netizens and the media. For example, one posting detailed an ongoing legal feud in an up-market residential community (gaodang xiaoqu) in the Pudong area, where residents were unhappy that the property developer had reneged on a promise to fully enclose the private neighbourhood and had rented out office spaces within the premises.3 Reportedly, the residents were concerned that the presence of offices would compromise the safety and exclusive character of their neighbourhood even though gates and fences had been erected around the premises. In scores of other postings, some urban residents complained that they had found themselves being ‘locked out’ of their own neighbourhood when up-market gated enclaves began to appear in the surrounding areas from the mid1990s. More significantly, a news posting by the state-run Xinhua news agency announced that from 2003 it would be mandatory for all newly built residential estates in Shanghai to be secured with surveillance cameras, infra-red detection systems and police warning devices at the neighbourhood boundaries. Although it is not required for walls and fences to be put up in all new residential estates, the guideline implicitly endorsed the building of gated residences in an attempt to promote neighbourhood safety and ‘modern’ housing management practices throughout the municipality. (Some of the local people I spoke to, however, criticized this policy as an attempt by the local government to ‘subcontract’ security to citizen groups and private companies in order to relieve itself of the financial burden of having to employ more police personnel on the ground.4

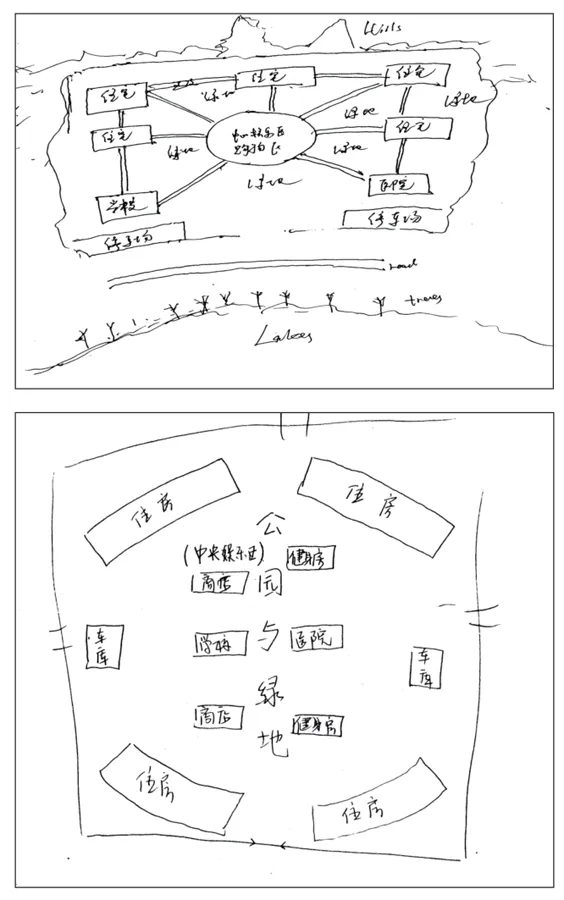

In my subsequent interviews and interactions with residents in Shanghai, I noticed that most people seem to take the presence of walls and gates in their neighbourhoods for granted. When I asked my respondents to draw what they would consider to be an ideal neighbourhood layout, many of their sketches depicted enclosed housing compounds with onsite facilities, parks and green spaces (Figure 1.1). Further discussion with the local residents on the different motivations for ‘gating up’ invariably led to the issue of culture and tradition in China. When it was suggested that gated residences are popular in Shanghai because of the public perception of a rising crime rate, a respondent5 who lives in an up-market suburban gated neighbourhood promptly corrected me:

If the above view is correct, then it would be reasonable to assume that the development of gated communities in China has been shaped by the ‘inner workings’ of culture and tradition more than by the ‘discourse of fear’ or any other factors commonly alluded to in the gated communities literature. In other related discussions, some scholars have suggested that the cultural and socialist legacies of China’s ‘collectivist-oriented culture’ and strong political control may be some of the underlying reasons contributing to the present phenomenon of gating in Chinese cities (Y. Huang, 2006), although the meaning and constitution of the ‘collectivist culture’ have been dramatically altered from one based on lineage, clans and work-unit affiliations to contemporary social divisions marked by emerging class distinction, consumption and lifestyle patterns (D. Davis, 2000). Webster et al. (2006:168) further observe: ‘Gates are unremarkable in China. As one developer put it, “walls are the tradition here” ’.

To be sure, Chinese architectural canons and urban history are replete with examples of enclosed housing forms ranging from the ancient walled cities in the Shang and Chou dynasties, through the residential wards (fangli) found in the Tang dynasty, to the enclosed courtyard houses (siheyuan) of the gentries and walled villages in the countryside, and later the walled ‘work-unit compounds’ constructed in the post-1949 socialist era (see Wheatley, 1971, Heng, 1999; Knapp 2000). As John Friedmann (2007) further points out, walls and gates have always been important symbolic markers of place in China. Quoting the work of Xu (2000), Friedmann notes that walls in China are used to define human relationships and serve as a symbol of the spatial ordering of life. Similarly, William Jenner in his book The Tyranny of History (1992:83–102) devotes an entire chapter to consider the pervasiveness of walls (both literal and symbolic), boundaries and enclosed spaces throughout Chinese history. In Shanghai during the Republican era in the 1920s and 1930s, as the historian Lu Han Chao (2000: 20) describes, ‘a typical residential neighbourhood in the city was a walled and gated compound consisting of several rows of identical attached houses’.

Given the long historical trajectory of walled housing traditions in China, it is perhaps not surprising that ‘culture’ and ‘tradition’ have so frequently been invoked as justifications for gating up in modern Chinese cities. Such ‘culturalist’ explanations are, however, problematic when one begins to probe deeper into the meanings of ‘culture’ and what kinds of ‘work’ culture performs. More pointedly, whose culture and tradition do present-day gated communities represent? Both walls and gates may reflect historical Chinese legacies and cultural practices of maintaining hierarchical human relationships, separating the sacred from the profane, the civilized from the barbaric, but, as Laura Ruggeri (2007:103) points out, whereas the residents of traditional walled villages belonged to a clan and shared common ancestors, the inhabitants of the new gated communities share only the dream of living in a safe and socially homogeneous environment. To explain away the modern gating phenomenon in contemporary Chinese cities as the product of an immutable cultural tradition or social norm is clearly to ignore the complexities of urban change and its underlying social–cultural processes.

Indeed, what is further incongruous about these strong culturalist claims and explanations for gating is that in modern China, where historical buildings and architecture including old city walls and gates have been wantonly destroyed, first in the socialist period (especially during the Cultural Revolution in the 1960s and 1970s) and later to make way for modern skyscrapers in the 1990s, it seems odd to suggest that the age-old cultural practice of building walled residential compounds is preserved intact and perpetuated ‘for the sake of cultural continuity’. By focusing only on the apparent cultural and physical form of gatedness in Chinese architectural styles, culturalist explanations fail to recognize how the underlying functions, meanings and symbolism of gates and walls have changed dramatically over time. Indeed, the ancient city gates (lao chengmen) and city walls (lao chengqiang) of old Shanghai that were first erected during the feudal times for protection against external threats (such as the marauding Japanese pirates off the coast) later marked the physical and symbolic boundaries between the ‘Chinese part’ of the city and the encroaching foreign concessions following the Opium War in the mid-nineteenth century. Interestingly, at the dawn of the Republican era in 1911, most of the city walls and gates in Shanghai were torn down by the new Nationalist government, who considered the ancient city walls an archaic sign of feudal backwardness that was incompatible with the modernizing visions of post-dynastic China.6 Gamble (2003:118–124) further observes that, although schools, offices, factories and housing projects in Shanghai are often gated and organized according to work-unit or danwei system, since economic reform many schools and local government offices have begun ‘tearing down walls and setting up shops’ (poqiang kaidian) by incorporating commercial functions within their compounds in order to raise revenue. Evidently, urban forms such as gates and walled compounds as well as their underlying meanings and symbolism do not fall into a fixed form of cultural stasis that is bounded in time and space.

Furthermore, such culturalist arguments seem to posit urban forms as the product of an ineluctable cultural logic and the dictates of a static cultural tradition. In many ways, such overtly culturalist explanations echo Duncan’s (1980) earlier objections on the ‘superorganic’ cultural explanation that seems to reify the notion of culture by assigning it independent ontological status and causative power. In his widely debated paper, Duncan makes a trenchant critique on the so-called ‘traditional’ American cultural geography during the 1960s and 1970s that he claimed had sought primarily to understand and explain human spatial variations by recourse to the notion of culture as a process sui generis —that is, as a thing irreducible to the actions of individuals (Duncan, 1980:185). Explanations of geographical phenomena using the superorganic argument are framed wholly at the abstract cultural level, giving short shrift to the role of individuals as active and meaningful social actors. Whereas Duncan’s critiques are levelled at what he sees as the methodological flaws of traditional cultural geography, the concern of this study here, without revisiting the debates (see D. Mitchell, 1995; Duncan, 1998; Mathewson, 1998; Shurmer-Smith, 1998), is to take his critique as a starting point to examine the cultural politics of gated communities in contemporary Shanghai.

In this book, I argue that gated communities in Shanghai cannot be adequately understood as a taken-for-granted urban cultural form as alluded to in the above discussions or the inevitable diffusion of an ‘American-style’ urbanism throughout the w...