- 549 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Fish accomplish most of their basic behaviors by swimming. Swimming is fundamental in a vast majority of fish species for avoiding predation, feeding, finding food, mating, migrating and finding optimal physical environments. Fish exhibit a wide variety of swimming patterns and behaviors. This treatise looks at fish swimming from the behavioral and

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Fish Locomotion by Paolo Domenici,B.G. Kapoor in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Biology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Waves and Eddies: Effects on Fish Behavior and Habitat Distribution

Paul W. Webb,1,* Aline Cotel2 and Lorelle A. Meadows3

Authors’ addresses: 1Paul W. Webb University of Michigan, School of Natural Resources and Environment, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-1041. E-mail: [email protected]

2Aline Cotel, University of Michigan, Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-2125. E-mail: [email protected]

3Lorelle A. Meadows, University of Michigan, College of Engineering, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-2102. E-mail: [email protected]

*Corresponding author: E-mail: [email protected]

INTRODUCTION

The natural habitats of fishes are characterized by water movements driven by gravity, wind, and other animals, including human activities such as shipping. The velocities of these water movements typically fluctuate, and the resultant unsteadiness is exacerbated when the flow interacts with protruding objects, such as corals, boulders, and woody debris, as well as with surfaces, such as the bottom and banks. The importance of these ubiquitous unsteady water movements is reflected in increasing annual numbers of papers considering their impacts on performance and behavior of fishes swimming in “turbulent flows” (Tritico, 2009) or “altered flows” (Liao, 2007). The ability of fishes to stabilize body postures and their swimming trajectories when these are perturbed by turbulent flows affects species distributions and densities, and hence fish assemblages in various habitats (Pavlov et al., 2000; Fulton et al., 2001, 2005; Cotel et al., 2004; Depczynski and Bellwood, 2005; Fulton and Bellwood, 2005). Understanding impacts of turbulence on fishes is also important as human practices modify water movements, and as turbulence-generating structures become increasingly common, such as propeller wash, boat-created waves, shoreline hardening to control erosion, fish deterrents, and fish passageways (see Chapter 3 by Castro-Santos and Haro, this book; Wolter and Arlinghaus, 2003; Castro-Santos et al., 2008).

Unsteady water movements have many effects on fishes but the mechanical basis for understanding the nature of responses is poorly known (Liao, 2007). At high levels, turbulence can result in mechanical injuries that injure and kill fishes. Here, we concentrate on a framework to explore interactions between fishes and turbulent flows relevant to sub-lethal effects. We argue that the distribution and strength of structures (orbits and eddies) in turbulent flow that would encompass a fish-like body are essential for the evaluation and prediction of locations chosen by fishes and their paths through turbulent flows. Thus, we first consider how fish-flow interactions may be approached as a physical phenomenon. Second, we discuss methods that have been used to quantify levels of turbulence. These discussions set the stage to revisit studies on swimming performance, behavior, habitat choices, and hence fish assemblages.

Turbulent Flow Structure and Frames of Reference

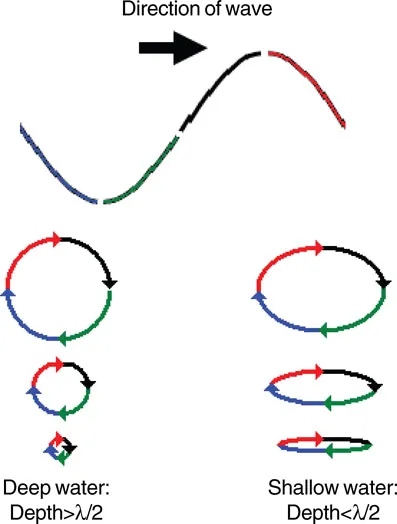

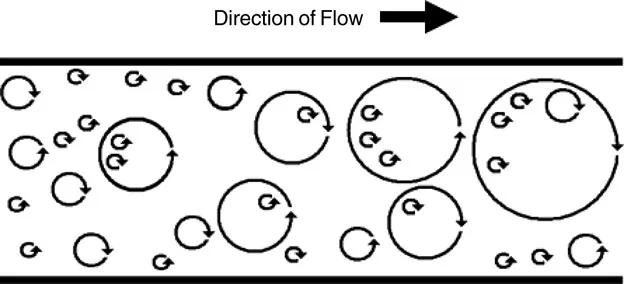

An important generalization in evaluating fish interactions with turbulent flows is recognizing that there are recurring probabilistic structures within unsteady water movements. We define these as “orbits” for periodic trajectories of water particles driven by non-breaking waves, and use vortices or eddies for structures in turbulent flowing water and breaking waves (Table 1.1, Figs. 1.1 and 1.2). It has been postulated that positive, negative and neutral impacts of unsteady water movements on fish performance and behavior reflect scale effects whereby only orbits and eddies of certain sizes present stability challenges and cause disturbances (Pavlov et al., 2000; Odeh et al., 2002; Nikora et al., 2003; Webb, 2006a; Liao, 2007). However, specific data are lacking, and much of the evidence is correlative or anecdotal.

Orbits and eddies vary widely in their distribution and in their sizes in natural habitats. Fish occupy much smaller domains than the entire water body, and hence will experience some subset of available structures. It is, of course, to be expected that fish choose habitat locations, or choose trajectories when swimming through the general flow, that minimize potential negative effects or maximize potential benefits. Thus consideration of fish interactions with unsteady water movements involves two linked systems with very different properties. The first is water movements in the environment. These are independent of the fish, and are determined by the factors creating waves and currents, and interactions of waves and currents with other habitat structures. The result is incident water movements that characterize aquatic habitats. Second, a fish (or other organism) responds as an embedded body within the incident water movements, experiencing a sub-set of these incident water movements.

Wave-induced water movements | Flow-induced water movements |

|---|---|

Groups of waves occurring at density discontinuities (mainly the air/water interface) travel across the surface formed by the discontinuity. | Water flows within a lake or stream bathymetry. |

In unbounded situations (lacking physical structures), a particle of water follows a circular path (here called orbits). | |

In bounded situations, the circular path becomes elliptical parallel to the bottom. | At high current speeds and/or large systems (high Reynolds numbers, high Froude numbers), the flow changes from laminar to turbulent. The turbulent flow is made up of eddies of many sizes. Surfaces and physical objects are sources of eddies due to the viscous nature of the fluid. |

A water particle returns very close to its starting position as each wave passes. | Water particles can follow various circular trajectories in eddies with a superimposed net downstream displacement, and hence do not return to their starting positions. |

Wavelength decreases as waves move into shallow water, eventually breaking creating turbulent water flows, i.e. flows containing vortices or eddies. | Turbulent eddies engulf surrounding water over time (as they age) and increase in size to eventually span the physical limits determined by the bathymetry of a system. |

Eddies calve smaller eddies as they age creating a range of eddy sizes and an energy cascade. The smallest eddies are defined as the Kolmogorov eddy size in flows typically encountered in fish habitats. These small eddies dissipate the energy of the turbulent flow as heat through viscous processes. | |

Common drivers: wind, density gradients of thermoclines and haloclines, boats. | Common drivers for vorticity (leading to the creation of eddies/vortices) are gravity (flow-water systems), wind and shear, viscosity (associated with flow effects and variations with temperature and density), baroclinic effects, breaking waves, and vortices shed by organisms during locomotion and feeding. |

The Reynolds number represents the ratio of inertial to viscous forces in flow. At small values, disturbances tend to be damped, and the flow is laminar. At high values. inertial effects tend to amplify disturbances and flow tends to be turbulent. The Reynolds number also provides the ratio of eddy sizes for a particular flow situation. | |

Detailed discussion of Froude number is beyond the scope of this review (see Denny, 1988). The Froude number is a ratio of inertial to gravitational forces, providing information of free-surface dynamics; cf. the Reynolds number, which is representative of the flow within the interior of the water column. As described in the text, fishes tend to be found in the lower part of the water column, when the Froude number will be less important than Reynolds number in determining the relevant flow. | |

The presence of an embedded body will modify the details of the incident water movements in the vicinity of that body. In many situations, the presence of a fish body will not have a large impact on those incident water movements, although vorticity shed during swimming may have a large effect when it meets downstream propulsors within the length of the body of a fish, or those of nearby fishes. Given the need for a conceptual framework towards understanding fish-turbulence interactions, especially given apparently contradictory results, and the likely small impacts where flow overtakes a fish, we chose to simplify the problem of fish-turbulence interactions, considering incident water movements independently of the fish presence.

Flow in Fish Habitat—The Incident Flow

Water movements in fish habitat are complex. Two major factors underlie this complexity, with different types of contribution from waves and from flow (Table 1.1; Figs. 1.1 and 1.2). The relative importance of the wave induced orbits within the water, and flow-induced eddies varies among habitats, although real-world flows in fish habitats are some combination of both.

Non-Breaking Wave-Induced Water Movements

In the realm of interest to this discussion, surface (and less often subsurface) gravity waves are created on the water surface by the action of wind as well as human-induced disturbances, such as boats. In unbounded water, a traveling wave is a progressive wave form emanating from a source. Waves are described in terms of: (a) wavelength, λ, the distance between crests or between troughs, (b) period, τ, the time taken for a recurring displacement of the wave to pass a location in an environmental frame of reference, and (c) amplitude, A the vertical displacement above and below mean water level. Height, H, is also used in describing waves, where H = 2A. The wave form travels with speed, or celerity, λ/τ. Shorter wavelengths travel more slowly than longer waves. The energy in waves also is gradually dissipated over time, this occurring more rapidly for shorter waves than for longer waves. Hence longer waves propagate farther than shorter waves (Denny, 1988).

Wave trains induce the periodic, essentially closed motions in water particles in the water column that constitute the orbits. A water particle in an unbounded aquatic system affected by a simple linear wave traces out a circular trajectory as a full wavelength passes by. The circular orbit attenuates exponentially with depth from the water surface, until it essentially vanishes at a depth of λ/2 (Fig. 1.1). In a real system, the circular orbits are not quite closed and there is some net translocation of the water particle in the direction of wave travel.

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Preface

- Table of Contents

- List of Contributors

- 1. Waves and Eddies: Effects on Fish Behavior and Habitat Distribution

- 2. Biomechanics of Rheotactic Behaviour in Fishes

- 3. Fish Guidance and Passage at Barriers

- 4. Swimming Strategies for Energy Economy

- 5. Escape Responses in Fish: Kinematics, Performance and Behavior

- 6. Roles of Locomotion in Feeding

- 7. Ecology and Evolution of Swimming Performance in Fishes: Predicting Evolution with Biomechanics

- 8. Sexual Selection, Male Quality and Swimming Performance

- 9. Environmental Influences on Unsteady Swimming Behaviour: Consequences for Predator-prey and Mating Encounters in Teleosts

- 10. The Effects of Environmental Factors on the Physiology of Aerobic Exercise

- 11. Swimming Speeds in Larval Fishes: from Escaping Predators to the Potential for Long Distance Migration

- 12. The Role of Swimming in Reef Fish Ecology

- 13. Swimming Behaviour and Energetics of Free-ranging Sharks: New Directions in Movement Analysis

- 14. The Eco-physiology of Swimming and Movement Patterns of Tunas, Billfishes, and Large Pelagic Sharks

- 15. Swimming Capacity of Marine Fishes and its Role in Capture by Fishing Gears

- Index

- Color Plate Section