1 Introduction

It is well known that productivity improvements fueled by technological change have contributed to a level of economic well-being that is higher today than at any time in our nation’s history. Further, sector-level increases in productivity growth coupled with consumer preferences have substantially changed the economic landscape of the United States over the last century. In 1900, for example, farming (agriculture) was the largest sector of the US economy. During the twentieth century, the number of farm workers decreased dramatically, while farm output grew fast enough to feed a growing population and have a surplus remaining for exports. In the second half of the twentieth century, manufacturing has followed a similar course—output grew continually while employment decreased. In both of these sectors, R&D led to innovations that significantly increased productivity and freed up labor for alternative uses (services).

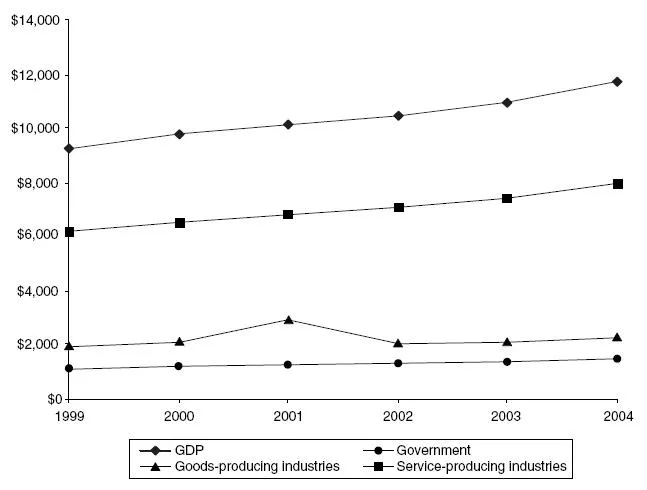

Today, the US private service-producing industries, hereafter referred to as the US service sector, is the largest sector in the US economy and accounts for an increasingly significant share of US gross domestic product (GDP).1 Figure 1.1 shows US GDP in billions of current dollars for the years 1999 through 2004, and it shows value added by industry for the government (federal, state, and local), the private-goods producing industries, and the private service-producing industries. In 2004, the service sector accounted for about 68 percent of GDP. If government services are included with serviceproducing industries, this contribution by the more broadly defined service sector exceeds 80 percent. Clearly, the service sector makes the greatest contribution to the US economy.2

Despite the contribution the service sector makes to the economy, people cannot agree on its definition.3 From a national data collection perspective, the Bureau of Economic Analysis within the US Department of Commerce defines service-producing industries to be the nonagriculture, forestry, fishing, and hunting; nonmining; nonconstruction; and nonmanufacturing industries. Table 1.1 provides the industrial and institutional composition of US sectors. From the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) data classification perspective, the definition of services is still evolving and the industries included change, albeit only a small amount, with each revision (Mohr, 1999).

Figure 1.1 US GDP and value added by industry, 1999–2004 ($ billions).

Table 1.1 Industrial and institutional composition of US sectors

Table 1.2 Traditional comparison of manufacturing and services sectors’ innovation-related characteristics

In addition to being the largest, the service sector is also the fastestgrowing sector. In 2004, according to Bureau of Economic Analysis data, the percentage change in value added by the service sector was 4.9 percent, compared to 4.2 percent for GDP in total, 3.9 percent for the private goods-producing sector, and 1.0 percent for the government.

Ironically, however, the service sector has historically been viewed as having little or no productivity growth and as void of an ability to innovate (Tether et al., 2001; Miles and Dachs, 2005). The sector has also been characterized as having low-paying jobs, low levels of technological dependence, and a relatively undeveloped level of institutional organization. In contrast, the manufacturing sector, which collectively dominates all other private goods-producing industries, was seen as the source of most innovations and thus the engine of economic growth.

Table 1.2 provides a partial comparison of innovation-related characteristics between the service sector and the manufacturing sector. The contrast between these two sectors is dramatic:

- Intellectual property rights are weak in services and strong in manufacturing.

- Service-sector firms pull new technologies in-house, whereas manufacturingsector firms develop new technologies and push them into the market.

- Traditionally defined R&D occurs in-house in manufacturing firms. Service-sector firms outsource their research and innovation activity.

- Innovation cycles are short in manufacturing and long in services.

- Products produced by service-sector firms are relatively intangible compared to the tangible nature of manufacturing products.

- Many manufacturing-sector firms operate on a national or global scale, whereas service-sector firms are more regional, or perhaps national, in spatial scale.

These innovation-characteristic differences are due in large part to the nature of R&D that occurs in services, more so than to the level of R&D conducted in services. In fact, service-sector firms are, on average, active in all aspects of R&D, contrary to the stereotypical description of that sector’s innovative activities. In 2001, according to National Science Foundation (NSF) data, nearly 45 percent of all industrial basic research was performed in the service sector, just over 36 percent of all applied research, and nearly 41 percent of all development research.

In recent years, the service sector has come to be viewed, both in the United States as well as in other industrialized nations, as a dynamic component of economic activity and growth. The observable growth in Internet and Web-based services and high-technology environmental services has brought attention to the service sector—knowledge-intensive services, in particular— as a significant contributor to economic growth (Howells, 2001). As pervasive and economically important as the service sector is, innovative activity in service-sector firms remains somewhat of an enigma; it is not well understood and not well defined because it differs dramatically from the traditional model of innovation in manufacturing.4 This book attempts to begin to fill this void.

The purpose of this book is to contribute toward a better theoretical understanding of innovation in the service sector by focusing specifically on the disparate nature and role of R&D in the service sector compared to the manufacturing sector. Based on this understanding of the nature and scope of R&D in the service sector—and taking as given that R&D is a critical input to the innovation process and innovation drives economic growth—we illustrate a theoretical model of service-sector innovation and compare and contrast it to the traditional theoretical model of manufacturing innovation.

Our model is capable of offering new insights into the innovation process, including not only an understanding of the role of R&D as an input into innovation but also the general knowledge flows that influence the level and scope of innovation within service-sector firms. In addition we investigate the role of entrepreneurial activity as it specifically relates to the service sector. In this way our model has the potential to provide a broad framework on which innovation and technology policies, as well as future empirical research, could be based.

As an overview, we set forth in Chapter 2 our model of service-sector innovation, and we contrast it with a traditional model of innovation in the manufacturing sector. Our model evolved from four extensive case studies of service-producing industries: the telecommunications industry, discussed in Chapter 3; the financial services industry, discussed in Chapter 4; the systems integration services industry, discussed in Chapter 5; and the research, development, and testing service industry, discussed in Chapter 6. Our model of innovation in Chapter 2 is not derived specifically from any specific industry; rather it is a composite of aspects of the innovation process gleaned from these four industry studies.5

In Chapter 7, we quantify firm-specific aspects of innovative activity in the service sector and compare them to the manufacturing sector using a representative sample of US public R&D-active firms. Finally, Chapter 8 concludes the book with a discussion of policy prescriptions related to the public sector enhancing innovation in the service sector.

2 Innovation in the service sector

Introduction

Much of the service sector’s growth since the early 1980s has been based on new services with significant knowledge content. A large share of the knowledge content in services is built on advances in hardware and software that were imported or purchased from the manufacturing sector. However, the service sector adds value in a different way than the manufacturing sector—by integrating purchased physical technology into systems. To add this value, service-sector firms have made considerable investments in capabilities such as systems-level integration. The impact of these investments has been substantial. R&D investments in service-sector information technology (IT) have generated an estimated rate of return of 196 percent, while noninformation technology investments in general have only created an 11 percent return (TASC, 1998).

For the US economy to continue to experience historical rates of productivity growth, the future performance of the service sector will be critical. Productivity growth is associated with applying resources to inventive and innovative initiatives as measured by spending on R&D. These expenditures, which currently represent only a few percentage points of GDP, support both basic research and applied research, which includes research into new specialized products for sale to industries and into the development of processes and process improvements internal to the innovating organization.

Traditionally, analysis of productivity growth in the service sector and the development of more accurate R&D estimates for that sector have suffered relative to other sectors of the economy. This is because economic output and productivity measures were originally developed in an era when services were a smaller share of the economy and the absence of more accurate information was not critical to policy making. In addition, because improvements to service outputs tend to be related to changes in quality rather than in quantity, productivity improvements are very difficult to measure.

Today that view has changed. Services are a large part of the economy and information technologies have, in many service industries, revolutionized the way business is conducted. However, use of the manufacturing R&D model to measure service-sector innovation activities is not completely appropriate and is likely to lead to biased estimates of innovative investments by the service sector.

Because the service-sector innovation process is a relatively new phenomenon and less structured compared to the manufacturing sector’s process, the nature and magnitude of service-sector innovative investments are less understood. Different taxonomies, objectives, and research processes create confusion over classification and data collection. This confusion makes NSF’s job of determining how to quantify total investments in service-sector R&D and describing innovation outputs difficult. The lack of an adequate R&D taxonomy and a consensus framework for analyzing service-sector R&D and innovative activity hampers the development and evaluation of public policy.

Taxonomies of service-sector innovations

Innovation and technological change in the service sector are increasingly dependent on internal service-sector R&D, in addition to technology acquired from the manufacturing sector (Pilat, 2001). However, there is concern that current NSF R&D statistics do not fully capture the level of innovative activity being performed within the service sector or, indirectly, the rate of change of innovative activity. NSF’s industrial R&D survey reports that manufacturing performed 62 percent and nonmanufacturing performed 38 percent of total industrial R&D in 2001. This distribution could be interpreted to imply that manufacturing may be performing a disproportionate share of national R&D relative to the sector’s contribution to economic growth and may be doing a preponderance of the innovative activity in the economy.

Recent studies have found that innovations in high-technology equipment have been increasingly the product of end-user R&D activities and less from vendor R&D. These end users, which are frequently service-sector firms, have firsthand understanding of what the technology needs are within an industry and how to innovate the existing technology to ultimately improve competitive advantage (von Hippel, 1988). For example, systems integration is an integral component of most service sectors’ innovative activities. As shown in Table 2.1, this process involves customizing components for specific applications. The service-sector firms (or specialized consultants) are essential in the integration process because of their detailed knowledge of the specific applications.

Table 2.1 Systems integration in selected US service firms

The term “innovation” has historically been used to encompass a wide range of processes that include both R&D- and non-R&D-related activities. In a broad sense, innovation may be new products, new processes, or new organizational methods that are novel and add value to economic activity. These developments or changes are shaped by interactions between a firm and various other organizations, including suppliers, collaborators, competitors, customers, technological infrastructures, and professional networks and environments. A firm’s innovation pattern depends on changes in the behavior of these organizations and the expectations of other organizations’ behaviors (Gallouj and Weinstein, 1997; Hauknes, 1998).

In general, innovation has also been described as any change in the characteristics of new products in terms of service, competence, and/or technical knowledge, brought about by evolution, variation, disappearance, appearance, association, or disassociation (Gallouj and Weinstein, 1997). In this light, innovation captures product and service modifications that may or may not be derived from R&D.

To date, most researchers believe that an accurate model of service innovation is still absent from the literature (Howells, 2000b). With a few notable exceptions, such as, for example, Barras’s reverse product cycle (Barras, 1986), the extant literature related to service-sector innovation focuses on differentiating service activities from manufacturing innovation paradigms, as opposed to building on the specific nature of service-sector products and process.

This state of the literatures suggests a need to integrate the unique traits of service-sector innovation into the existing taxonomies and innovation paradigms. The goal is to capture more diverse types of innovation in conceptual models of innovation, including what was once two distinct segments of the economy but has over time become increasingly less disparate (Gallouj and Weinstein, 1997; Amable and Palombarini, 1998). Although existing taxonomies have begun to address how innovation occurs in service firms, much more work remains to be done in terms of modeling an innovation system that incorporates services. The model we posit in this chapter is only one step toward that end.

Recent efforts to incorporate the service sector into models of innovation include, for example, Pavitt’s (1984) taxonomies for classifying sectoral patterns of technological change. By dividing a national economy into three sectors—supplier-dominated, production-intensive, and science-based, Pavitt outlined a dynamic relationship between technology and service industries. Professional, financial, and commercial services are captured in the supplier-dominated category. However, the firms associated with this sector were primarily described as firms that expend few resources developing processes and products, usually having weak in-house R&D capabilities where most innovations come from the supplier of equipment and materials.1

Soete and Miozzo (1989) have taken the Pavitt model a step further by expanding on the supplier-dominated sector, offering two new classifications: a production-oriented category and an innovative-specialty category. The production category includes those service firms performing large-scale processing and administrative activities and developing physical or information networks. The specialized technology suppliers’ category includes firms performing science-based activities to develop proprietary technology through innovation.

In addition to understanding the distinctions between manufacturing and service-sector innovative activities, a second line of research has focused on the differences between products (e.g. new services) and process (e.g. new organizational and delivery processes) within the service industry. Gallouj and Weinstein (1997) make this distinction by dividing innovation for the service firm into two classifications: technical characteristics (front-office t...