![]()

1 Post-reform urban conditions

Introduction

With China's transition from a planned to a more market-oriented economy, Chinese cities have been undergoing significant transformation. The cities are at the centre of this transition, and now play a very important role in overall economic development. In the Eleventh Five-Year Plan, raising the level of urbanization is adopted as a major policy instrument to promote economic growth. By 2015, the country anticipates having half of its population in cities and towns (Pannell 2002: 1578). It is estimated that China's urbanization level will increase to 75 per cent by 2050, and that the urban sector will contribute over 95 per cent of the national economy. Accordingly, more than 600 million people will move from rural areas to the cities (People's Daily 20 July 2002). There will be fifty ultra-large cities with a population of more than two million, over 150 large cities, 500 medium-sized cities, and 1,500 small cities (ibid. 20 July 2002). Membership of the World Trade Organization (WTO) is greatly stimulating the integration of the Chinese economy into the global economy. Chinese cities are now becoming one of the major bases for global commodity production. China's endeavours to organize international affairs such as the Olympic Games in 2008 in Beijing and the World Expo 2010 in Shanghai are providing additional momentum for urban restructuring. Large-scale urban redevelopment schemes have been carried out to rebuild China's globalizing cities. Stimulated by the inflow of foreign investment and the expansion of import and export trade, Chinese cities are building themselves towards becoming ‘global cities’.

Visitors to China's large cities, such as Beijing and Shanghai, never fail to notice how dynamic they are. John Friedmann (2005: x), in his book China's Urban Transition, comments on how writings about China become ‘snapshots’ taken at a single point in time, which will soon acquire the feel of a distant, bygone era: ‘the portraits of Shanghai, Dalian, Hangzhou, Wuhan, and Beijing toward the end of the Maoist era strike a more contemporary traveller as coming from another century. And yet, the time that has elapsed is less than thirty years!’. Joshua Ramo, a senior editor of Time magazine, provided a vivid personal observation of the changing urban scene in Shanghai:

If you are lucky enough to fly into Shanghai in the late afternoon, up along the coast from Hong Kong, you will be treated to a remarkable sight. As the sun fades to twilight, the pink and then purple light reflects back up at you, first off the East China Sea, then off the Huangpu River, and finally off the 1,000 dappled mirrors of Shanghai's exploding commercial district. After you land, and as you make your way out to a taxi at Hongqiao airport, you will be greeted by another sight – hundreds of twinkling lights atop the city's skyscrapers and construction cranes.

(Ramo 1998: 64)

However, even this observation soon became that of the last century, because before the turn of the century you would land in Shanghai's new Pudong International Airport, where the private jets of the CEOs of the world's largest 500 multinationals lined up for the ‘99 Fortune Global Forum’. Pamela Yatsko (1996: 69), a journalist from Far Eastern Economic Review, made the following report:

throughout the city, whole blocks are being flattened, turning parts of the former ‘Paris of the East’ into huge construction sites – a chorus of cranes, jack-hammers and bulldozers chiselling out the foundations of skyscrapers, elevated expressways and subway tunnels. Architects are having their fling with modernism – designing huge glass-faced office complexes and luxury apartment blocks.

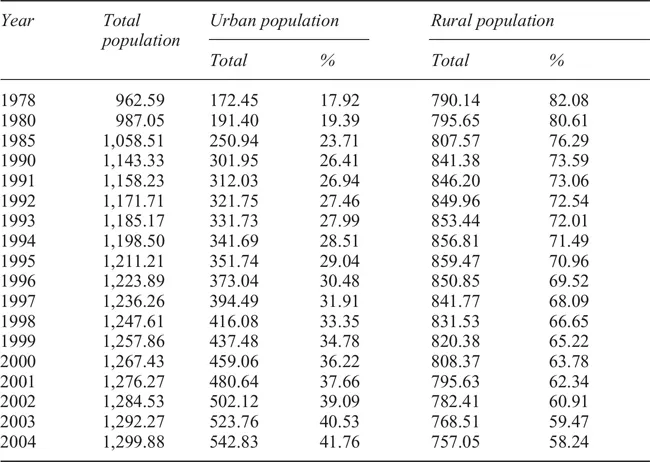

Indeed, China has seen fast urbanization. According to the State Statistics Bureau (2005a), the urbanization level in China had grown from 17.9 per cent in 1978, when the reform began, to 40.5 per cent by the end of 2004 (Table 1.1). Although the definitions of the ‘urban population’ and the level of urbanization continue to bother China scholars because of the complex relations between geographic boundaries and the household registration system,1 the statistics do reflect the pace of urbanization. China's fifth population census, held in 2000, reveals a total population of 1,265.83 million, of which 455.94 million were urban population (Zhou and Ma 2003). This figure gives an urbanization level of 36.09 per cent. The Ministry of Construction (2005) reported that at the end of 2004, there were in total 661 cities, with an urban population of 340.88 million and an administrative area of 394,200 square kilometres. China's urban landscapes are being forcefully transformed: in cities such as Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou, skyscrapers mushroom in city centres; elevated and multilevel fast roads extend to suburbs where gated housing estates and development zones are scattered; and infrastructure is being built at an unbelievable pace.

Table 1.1 Growth of urban population and increasing urbanization level in post-reform China, 1978–2004 (millions)

Source: State Statistical Bureau (2005a, 2005b).

Notes

1 Pre-1982 figures are population with urban household registration permits; figures from 1982 to 1989 are adjusted based on the 1990 census; figures from 1990 to 2000 are adjusted based on the 2000 census; figures from 2001 to 2004 are calculated based on sample calculation of population changes.

2 Pre-1982 urban population is the total population in all urban jurisdictions, while rural population is the population in counties but excluding towns. Urban population from 1982 to 1999 includes the population in cities that have districts, the population in streets in cities that have no district designation, the population of the residential committees in the towns of the cities that have no district designation, and the population of residential committees in the towns under the jurisdiction of counties. Rural population during the same period includes those who are not classified as urban population. Classification of urban and rural population after 2000 is calculated based on ‘On Statistical Classification of Urban and Rural Population’, enacted by the State Statistics Bureau in 1999.

The question is, how has China entered into an urban age so fast? Current studies on China tend to focus more on the political, social and economic aspects. There is a growing body of literature on Chinese cities and regions (e.g. Chung 1999; Li and Tang 2000; Marton 2000; Smith 2000; Wei 2000; Cartier 2001; Logan 2002; Ma and Wu 2005; Wu 2006; Wu and Ma 2006; see also the Routledge Studies on China in Transition series; for a review of recent literature on urban China see Ma 2002). Zhang W.W. (2000) observed that research on China's economic reform mainly focuses on rural, urban (enterprise and labour), macroeconomic (price, fiscal, monetary), and foreign trade aspects, and usually neglects land and housing reforms within the cities. However, land and housing reforms are crucial for the shift in the strategy of economic development. Chan (1994) examined urban growth from the strategy of economic development in Mao's period, but there has been a lack of systematic analysis of how urban growth is now not only the outcome but also part of overall economic strategies. There is a need to interpret overall post-reform urban development in a more systematic manner. In addition, the interpretation should be situated in the wider context of market formation, state intervention, and spatial restructuring in the world. This book will examine the three key elements in this coming urban age in China: market, state, and space.

Post-reform urban conditions

What are the conditions under which such a restless urban landscape is produced? The key theme of the post-reform urban scene is ‘commodification’. Such a relentless change occurs in virtually every aspect of Chinese urban life, ranging from commodification of labour (e.g. migrants being attracted into the city to provide cheaper forces in the city) to privatization of productive resources (e.g. converting the ownership of state-owned enterprises, SOEs, to share-holding companies), and finally to commodification of the built environment itself (e.g. establishing a leasehold land system and commodity housing markets).

However, it is not a simple task to establish a market economy within a primarily non-market society. Before the introduction of market mechanisms Chinese society was governed by a totalitarian state, in the sense that the state and society were so tightly entangled and embedded in each other that it was hard to distinguish the boundary between them (hence the term ‘totalitarian'). The transformation of the economy towards a market-oriented one therefore had to be accompanied by the reorientation of the society towards a market one.2

There is now a wide consensus that economic reform in China has been gradual, different from the Eastern European style of ‘shock therapy’. However, this understanding does not contradict the notion that reform is pervasive and in fact generates rather radical solutions. Zhang W.W. (2000: 4) made the following assessment:

China's economic reform has largely destroyed the economic and institutional basis of totalitarianism that had once prevailed in the country, and has transformed significantly the nature of China's economy, state and society: a transformation from a rigidly planned economy into an increasingly market-oriented one; from an anti-market totalitarian state into a largely pro-business authoritarian one; and from a rigid and administratively ‘mechanic’ society into a fast-changing, informally liberalized and increasingly ‘organic’ society.

Yao (2004: 255) also assessed the extent of privatization since the new constitutional amendment enacted in early 1999, which elicited a new round of privatization: ‘it was estimated that 70 percent of the SOEs had been privatized by the end of 2002’ and ‘by international standards, gaizhi [changing the system] thus qualifies as a property-rights revolution, although this revolution has been largely silent’.

Hui Qin (2003: 110), a renowned Chinese scholar, argues that ‘[Western economists] are under the illusion that the Chinese transition is more ‘gradual’ and ‘socialist’ than the East European. In reality, the process of ‘dividing up the big family's assets’ has been proceeding as ‘relentlessly in China as in Eastern Europe’. And such a trend began as early as in the 1990s: ‘We already sensed that a Stolypin-style combination of political control and economic ‘freedom’ was brewing. With Deng's southern tour of 1992, it duly arrived’ (Qin 2003: 94).

Economic liberalization in fact helped the state to overcome the crisis of revenue deficit in the late 1970s and early 1980s, and enhanced its governance capacity. Paradoxically, resource mobility does not lessen state power; rather, competition originating from mobility legitimizes the role of the state, which is in the process of transition from defending a ‘proletariat ideology’ to promoting ‘economic rationality’. The study of the function of the state in economic development has paid due attention to ‘industrial policies’ (e.g. Johnson 1982; Wade 1990) but not enough to urban policies in defending and enhancing the state's capacity in the face of globalization.3

The central theme of this book is to enquire how the market institution of urban development is constructed, what the state's role is in this process, and what the implication is for urban space both as the outcome and as a means through which such a goal is achieved. The enquiry therefore is built upon three components: state, market, and space in post-reform urban development.

Applying the perspective of regulation theory about the regime of accumulation,4 the transition of China's urban condition can be summarized as moving from state-led extensive industrialization to urban-based intensive urbanization. The former is built upon state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and the related government branches in each industrial sector built into a hierarchical structure.5 An accompanying mode of regulation is the redistributive state.6 The new regime is characterized by urban-based agglomerative economies. Such a change involves reconceptualization of the city as the means to overcome constraints on accumulation through: (1) prioritizing this scale for intensive accumulation, e.g. by increasing the level of urbanization and allowing rural to urban migration, and subjecting the rural counties to the leadership of the central city, thus extracting resources for the city; (2) commodifying urban space through land-leasing and commodity housing; and (3) adopting global-oriented production through foreign investment and joint ventures.

The commodification of urban development has begun to show its powerful effect on economic growth. Since the mid-1980s, the Chinese economy has struggled to find an engine of growth. With the mushrooming of township and village enterprises (TVEs) and later foreign-funded joint ventures, state-owned enterprises as the core of the state-centred accumulation regime came under severe challenge. Large-scale restructuring thus began in the 1990s and generated millions of laid-off workers. The system of SOEs has since then been subject to transition. The objective of transition is then to change the organization of production to commodity production. To achieve this objective, property rights are being re-bundled, including but not limited to the creation of share-holding companies. Privatization is sweeping, separating the state as the ultimate owner from the leaseholder or shareholder who can draw legitimate benefits. This often leads to the transfer of state resource to private hands. So-called gradual reform in China is thus politically tardy but economically radical. The result is that the Chinese economy has grown out of the plan (Naughton 1995) and become more market-oriented.

The real-estate sector has been picked as a new growth engine. The decline in the state manufacturing sector is in sharp contrast to profitability in real-estate projects. Selling factory sites to real-estate projects has become a common practice. Accompanying the closing-down of traditional manufacturing industries, and the developing real-estate business, is the shift of capital from the production circle to the circle of the built environment.7 During the building boom in the early 1990s urban development absorbed substantial capital, until the macro-economic adjustment after the Asian Financial Crisis. However, with sluggish domestic demand, not so much because there is a lack of need as because of consumer confidence, the real-estate sector has again been pushed to stimulate domestic demand by abolishing in-kind housing allocation in 1998 and creating an imaginative vision of ‘home’ to capture the demand of the upwardly mobile social stratum. Stimulated by recent entrance to the WTO, places such as Shanghai have suddenly seen two-digit property price inflation since 2002.

To sum up post-reform urban conditions, there is a tendency towards increasing resource mobility (in particular capital mobility) and social complexity, which on the one hand has weakened the governing capacity of the state, although on the other hand economic decentralization has granted the local state more autonomy to regulate the economy. The capacity for capturing mobile resources is thus dependent upon the strength of local agglomeration. Therefore, the cities struggle to build larger and larger urban areas. Intercity competition might be rhetoric – an excuse for city beautification and prioritizing economic policy over social policy in China – but the intensity of resource competition is substantial and real. The construction of a new city square provides not only an attractive image8 but also a platform to launch a series of real-estate projects and bring in new investment opportunities in the surrounding area.

Now we begin to examine market, state, and space respectively.

Market: establish an institution

After two decades of housing and land reforms the question is now, to what extent has China developed ‘genuine’ housing and land markets? In other words, what is the current level of commodification in urban development, and how pervasive is the market mechanism? To answer these questions, we need to go beyond the housing and land market and understand the overall marketization of urban ‘space production’.

The land market in China is a highly fragmented one. Yeh and Wu (1996) reveal that the dual urban land market is characterized by the co-existence of administratively allocated land and leased land. For China's land market in general, there are in fact two ‘segmented primary markets, one used by the state to allocate urban land and the other by rural collectives to allocate collectively owned land, and both are dual-track markets’ (Ho and Lin 2003: 705). They further comment:

The new land system permits use rights obtained on the primary market to circulate in segmented secondary markets. Four such markets have developed: use rights to state land obtained through conveyance are permitted to circulate in the secondary market in the commercial sector; user rights to state land obtained through allocation may circulate among state users within the urban-state sector; use rights to contracted agricultural land may circulate as long as the land is used for agriculture purposes; and finally, use rights to collectively owned rural construction land may circulate within the rural collective sector.

(Ho and Lin 2003: 705)

Besides the complex segmentation, Ho and Lin (2003: 705) observe that:

In 1998, the most recent year for which data are available, urban land allocated administratively was nearly four times that assigned through conveyance. And of the land assigned through conveyance, nearly 90 per cent was by negotiation, the method that is least transparent, least competitive and most easily manipulated. Negotiations behind closed doors have created opportunities for manipulation and corruption.

This observation leads to an impression of a very immature and underdeveloped land market. But why was the approach of negotiation always preferred, by the city government, to public auction or bidding? There could be several explanations, which are not mutua...