1 INTRODUCTION

The majestic presence of the river in the midst of uncultivated lands, which, with the help of its waters, would need so little labour to make them productive, takes a singular hold on the imagination. I do not believe that the east bank has always been so thinly peopled . . . it is probable that there was once a continuous belt of villages, their site being still marked by mounds.

(Gertrude Bell, 1910: 518)

We have had no rain since we came to Carchemish, but generally sun, with often after midday a gale from the North that drives the workmen off the top of the mound, and tosses up the dust of our diggings . . . If one can struggle up to the top of the mound and hold on one can look over all the plain of the river valley up to Biredjik and down to Tell Ahmar, and over it all the only things to show out of the dust clouds are the hills and tops of the tells.M

(T.E. Lawrence, quoted in Garnett 1938: 98–9)1

The striking landscape and rich archaeological potential of the northern Euphrates Valley could not fail to affect even Gertrude Bell and T.E. Lawrence, two individuals who were to figure prominently in the shaping of the modern Middle East.

In the recent past, many more than a few travellers and casual archaeologists have turned their attention to the antiquity of the land of Syria, including the Euphrates River Valley. Especially in recent decades, Syria has become the major focus of many investigations, when archaeologists, no longer able to access the antiquity of countries such as Iraq and Iran, shifted their focus to the heritage of Syria and its rich array of ancient architectural remains and artifacts. Their investigations have proven tremendously significant. They have demonstrated that we can no longer regard the ancient land of Mesopotamia, defined by the alluvial valley of the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers of southern Iraq, as the sole source of the great cultural transformations taking place at the dawn of history. Now we must realize that Syria too partook in many of these radical major changes.

Especially important were developments taking place in ancient Syria during the third millennium bc. This time period, often referred to as the Early Bronze Age, was witness to a dynamic growth of complex societies and the rise of urbanism. These new advancements had a major impact on human populations, bringing about dramatic changes to their political systems, and radically reorganizing their social and economic structures. Many of these pivotal developments are now well attested in the archaeological record. Investigations have shown, for example, that in the northeastern corner of Syria, along the banks and tributaries of the Khabur River, large and densely populated cities, supported by the agricultural produce of vast tracts of fertile fields, began to spring up all over the landscape. Settlements such as Tell Leilan, grew as large as 100 ha by 2600 bc, truly attesting to the early success of urban growth in this region. The discovery of an administrative archive of cuneiform tablets at the site of Tell Beydar, confirming that people of the Khabur region were literate, lends further support to this picture of urban progress. Cities also emerged in western Syria, in the agriculturally rich Orontes River Valley and the dry farming plains to the south of Aleppo. Here, the most well-known of ancient Syrian cities, Ebla, is renowned not only for its immense and rambling palace but for its archive rooms, found full of thousands of inscribed cuneiform tablets describing all the political activities and economic accounts of the powerful Eblaite king and his numerous officials.

In light of such discoveries in Syrian archaeology, the land of southern Mesopotamia must now be seen as but one of many regions in the Near East where early civilizations arose. More importantly still, ancient Syria’s urban transformation should not be regarded as having derived solely from its contact with Mesopotamia, its cultural achievements being but pale imitations of the truly monumental advances engendered in the south. As the archaeological evidence has proven, many aspects of Syrian cities are original and distinctive, and they attest to the vibrant, independent character of their people and culture.

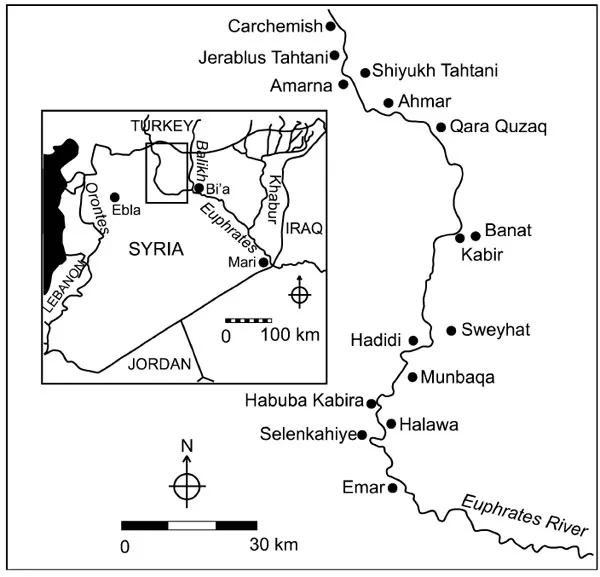

The northern Euphrates River Valley perhaps stands out as one of the most remarkable areas in which early urbanism evolved in Syria (Figure 1.1). This riverine region, stretching for about 100 km from the modern border of Turkey and Syria down to the area around the ancient site of Emar, supported several flourishing settlements during the third millennium bc. Settlements were established near the banks of the river and on the higher terraces. Here they were able to take advantage of the agricultural potential of the alluvial valley and commercial traffic of the river itself, as well as the pastoral and hunting opportunities provided by the vast upland steppe plateau that rises up on either side of the river valley. For several centuries populations increased and flourished, and settlements grew into substantial centres featuring many urban trappings.

Figure 1.1 Locator map of Syria (left), and map of Euphrates River, with principal EB sites (right).

Such settlements were well defended by monumental defensive systems. They had communal places of worship, usually in the form of large temple structures surrounded by sacred enclosures. Some settlements featured lavish, multi-roomed buildings, which probably functioned as the residences and administrative headquarters of wealthy or prominent elites. An array of fine copper and bronze metalwork and other manufactured goods such as pottery demonstrates that craft specialists with well-developed skills were present. Extensive sectors of housing, well spaced out and accessible by straight, interconnecting streets, grew up in these third millennium towns. Associated with these living communities were large cemeteries for the dead, containing impressive rock-cut graves and grand stone-built tombs, many filled with rich assemblages of precious or rare grave offerings. Finally, monumental funerary tumuli, towering high above the river valley, provided an important focus of community identity. Together, this evidence demonstrates that the northern Euphrates River Valley was not merely a backwater of simple farming and pastoral villages. It also had a sophisticated, thriving culture, characterized by many of the same urban attributes as its Mesopotamian and Syrian neighbours.

On the other hand, several notable differences serve to distinguish settlements that grew in the northern Euphrates Valley from those found elsewhere. Although some settlements grew considerably in size, supporting fairly large populations, their scale was modest compared to that of the cities of southern Mesopotamia or even the Khabur Plains of northeastern Syria. The largest northern Euphrates city in Syria expanded to no more 56 ha during the third millennium bc, only half the size of some of the cities of the Khabur Plains, and only a small fraction of the grand urban centres of the south. Other northern Euphrates settlements were even smaller, most being less than 10 ha in area.

Another striking difference from the south was the absence of rigid settlement hierarchies and the associated presence of city-states in the northern Euphrates Valley, a development that marks many urban societies elsewhere in Greater Mesopotamia. While it is possible to identify clusters of settlements of varying sizes in some parts of the region, these site aggregations do not appear to exhibit rigid hierarchical structures. They are not defined by central or core cities that possessed all the administrative and organizational apparatus to govern and control the political, economic and religious affairs of the smaller, simpler, agro-pastoral communities that surrounded them. On the contrary, what we see in the Euphrates region is a more evenly dispersed arrangement of political, economic and religious authority, such that even the smallest settlements exhibited significant displays of complexity. These smaller riverine communities were characterized, for example, by impressively rich tombs and monumental temples. Because of these unexpected features and the unusual settlement configurations they reflect, it is not appropriate to use the term ‘city-state’ to refer to any settlement cluster within the northern Euphrates region. This designation suggests too many notions of a central-place political ascendancy and economic domination that are simply not well attested.

As the evidence will show, however, it is impossible to deny the existence of local elites and some degree of social stratification in the northern Euphrates Valley. Yet, we submit that there existed at the same time a contrasting or opposing dynamic that appears strongly to have constrained the degree to which elite power and authority could take hold and grow. Few powerful individuals or families appear to have risen to such a level of authority that they could control the entire economic base and administrative systems of the community in which they lived. This situation is reflected by the rarity of palatial complexes or public buildings from which such pre-eminent authority would have emanated. Such architectural complexes have only been found at a few sites and appear to have existed only towards the very end of the third millennium bc. In contrast to these complexes, most of the evidence from the northern Euphrates River Valley appears to reflect a more heterarchically structured society, in which there existed several coexisting and overlapping sources of power and political-economic control.

Although archaeological manifestations of such heterarchical organization are more difficult to identify than the physical markers of social stratification and elite control, they are nonetheless apparent in some contexts. We find, for example, a kind of group-centred ideology existing at the remarkable mortuary centre of Tell Banat. At this site, monuments in the form of towering tumuli and their accompanying burial rites reflect corporate notions of inclusion in which all markers of individual social status and personal wealth were extinguished (Porter 2002b: 166). But nonetheless, in contrast, these ideals of corporate belonging do not stand alone at Tell Banat. The presence of well-built, lavishly furnished tombs at this site and elsewhere undoubtedly mark the burial places of wealthy, elite members of society. Our evidence suggests, therefore, that the society of the northern Euphrates was varied. It seems inappropriate to characterize it as either a ‘corporate’ or a hierarchically structured society. Rather, we must acknowledge the presence of both systems, sometimes existing in tension and opposition to one another, while at other times coexisting in a state of mutual interdependence and complementarity (Porter 2002b: 169).

All the differences we have outlined suggest that we should regard the Syrian Euphrates Valley as a unique place. On the one hand, it is defined by many of the same urban attributes that may be observed in other regions of the Near East. On the other hand, it developed distinctive social, political and economic structures differing significantly from examples of ancient urbanism observed elsewhere. In the chapters that follow, we will discuss a variety of factors that, in our view, contribute to this region’s unique character. We will suggest how these factors contributed not only to long settlement life and cultural continuity but how they enabled the region to withstand socio-political and environmental stresses at the end of the third millennium.

The archaeological heritage of the Euphrates Valley of Syria has been known for well over a hundred years. Early twentieth-century investigations at the site of Carchemish by British archaeologists, and at Tell Ahmar by the French, confirmed that the third millennium was an important period of settlement in this region (Thureau-Dangin and Dunand 1936; Woolley and Barnett 1952). Not until the last few decades of the twentieth century, however, were serious, systematic attempts made to explore this region’s antiquity. The greatest strides came with the archaeological salvage work initiated prior to the construction of two large dams across the Euphrates. These dams led to the formation of massive lakes that submerged the majority of ancient sites located in the river valley. Before completion of the first dam at Tabqa in 1973, surveys and archaeological salvage work were conducted in the southern section of the region, from el-Qitar in the north, extending well below the site of Meskene/Emar in the south (Van Loon 1967; Freedman 1979). The more recent Tishreen hydroelectric dam prompted investigations of the northern-most stretch of the Euphrates in Syria, from just below the site of Jerablus and the ancient site of Carchemish in the north, to the site of el-Qitar in the south (McClellan and Porter in press). The bulk of information presented in this book derives from the archaeological reports produced by the archaeological teams carrying out salvage operations in these Tishreen and Tabqa Dam regions.

CHRONOLOGY

The time period that we present in this book covers over 1,000 years of human settlement in Syria. It not only spans all of the third millennium bc but it also includes the last centuries of the fourth millennium and the first 100 years of the second millennium (c.3200–1900 bc). For absolute dates in this book we have followed the so-called ‘middle’ chronology, which reckons all developments backward in time from the fall of Babylon in 1595 bc (Akkermans and Schwartz 2003: 13). It is possible that the ‘low’ chronology advocated by several scholars in the recent past may eventually prove to be more accurate (Gasche et al. 1998). Nevertheless, since the majority of archaeologists working in the northern Euphrates Valley up to this point have used the ‘middle’ chronology, we do not wish to cause confusion by deviating from this conventional practice.

One of the biggest dilemmas facing scholars investigating the material remains of the northern Euphrates region of Syria is the terminology used to describe the passage of time during the third millennium bc. The general designation ‘Early Bronze Age’ is almost universally applied to this region, but given that this age covers over 1,000 years, a periodization that divides this time into smaller phases is needed to chronicle the more precise sociopolitical changes and cultural transformations taking place.

Several chronological terminologies exist, but few are appropriate. The third millennium bc of southern Mesopotamia is divided according to historical developments that chronicle the establishment of the Sumerian Early Dynastic city-states and the subsequent rise and fall of the Old Akkadian and Ur III empires (ED I, II, III, Akkadian and Ur III periods). Although the Syrian Euphrates is contemporary with these developments and shares some cultural features with southern Mesopotamia, its abundant differences cannot justify the adoption of this southern chronological sequence. The lack of perfect synchronisms between the two regions, gleaned primarily from inscriptional evidence, further urges against the use of the southern Mesopotamian chronology.

The sequence devised for the Amuq plain of southern Turkey (phases G–K) (Braidwood and Braidwood 1960), the Levantine sequence, which applies principally to Palestine and Jordan (EBI–IV), and even the recently devi...