1

LANGUAGE AND REPRESENTATION

The guidelines

What constitutes discriminatory language, or indeed whether language can even be said to be discriminatory or not, was widely debated in the late twentieth century and remains far from settled today. Each year the media report continuing skirmishes over language, as the following examples show:

- In the United States in 2001, the Cartoon Network, which had planned a Bugs Bunny festival showing every Bugs cartoon made since 1938, withdrew certain of the series made in the 1940s which depicted Bugs ‘being offensive to blacks, Indians, Eskimos, Germans and Japanese’. The original plan had been to show the cartoons late at night with the disclaimer: ‘These vintage cartoons are presented as representative of the time in which they were created and are presented for their historical value’. Fearing a backlash, however, the network executives banned their showing altogether (Courier Mail 2001a).

- In the United Kingdom a few months later, the British Advertising Standards Authority dismissed a complaint against the use of the word ‘kraut’ – used as a term of abuse meaning ‘German’ since World War I – in an advertisement, on the grounds that the word is ‘a light-hearted reference to a national stereotype unlikely to cause serious or widespread offence’. The German Embassy disagreed (Courier Mail 2001b).

- In Melbourne, a large advertising billboard greeted travellers leaving the main airport with an invitation: ‘Sexist. Insulting. Demeaning. Vote for your favourite billboard’. That same month a top-rating Australian TV medical drama had a nurse describe a patient as ‘mentally challenged’.

- In Japan, academics caused a fuss by proposing to rename birds, animals and fish because elements of their popular names, specifically the words ‘dwarf’, ‘blind’ and ‘stupid’, were deemed discriminatory. The scientific names of the creatures were to remain unchanged. ‘Mekura kamemushi’ (blind bugs, the popular name for insects of the Miridae genus) and ‘mekura unagi’ (blind eels) have both had their names changed to avoid the use of the contested word ‘mekura’. Penguins once referred to as ‘kobito’ (dwarf penguin) are now called by the English name ‘fairy penguin’ to avoid reference to dwarfs. A national survey found that 37 of 354 wildlife facilities across Japan have removed a creature from display because its name might offend sensibilities (Mainichi Shimbun 2001a).

More recently, in November 2004, the New South Wales Administrative Decisions Tribunal deemed two well-known broadcasters and their Sydney radio station guilty under the Anti-Discrimination Act of homosexual vilification in on-air comments about two gay contestants in reality TV show The Block (Sexton and Leys 2004).

Clearly, interest in linguistic stereotyping remains keen. But the interest does not always relate only to tightening controls on language: in October 2004 the West Australian government passed an amendment to proposed racial vilification laws in that state, permitting the terms ‘pom’ (British migrant), ‘wog’ (person of Semitic or Mediterranean background) and ‘ding’ (person of Italian descent) to be used without fear of prosecution because they are ‘light-hearted’ references to another person’s race (Mayes 2004). In other Australian states such as New South Wales and Victoria, the use of these words can lead to civil proceedings. It is unclear whether any ‘wogs’, ‘dings’ or ‘poms’ were consulted in arriving at this decision.

Language and power in any given society, as has long been recognized, are closely linked. ‘Disputes about the proper names for people and things are ultimately power struggles. Who has the right to decide how a person shall be called decides how that person shall be classified and defined’ (Romaine 1999: 298). The most immediately visible examples of the power plays implicated in language use – leaving aside the wider issues of minority languages within a society and concentrating on language use within the major language – are sexist and racist language, along with other kinds of language which stigmatizes or excludes certain sections of the community.

Many books have been written in Japan on derogatory language, both academic and non-academic, ranging from descriptive collections of incidents where offensive language has been used and challenged (Takagi 1999) to sociological dissections (Yagi 1994). Most of them have appeared from the mid-1980s to the present, with the majority being published in the early 1990s (although some were much earlier). Yagi (1994: 1–2) speaks of three waves of debate over discriminatory language occurring roughly ten years apart, in the mid-1970s, mid-1980s and mid-1990s. Whereas the first two were driven by activist groups or those closely involved with them, the third centred around writers; the first two took place in relatively closed contexts, but the third made headlines in the press, on TV and in popular magazines. We shall see as this book proceeds how each stage unfolded, and will add a fourth stage of our own.

The terminology of the debate includes ‘sabetsu yōgo’ (discriminatory language), ‘sabetsugo’ (discriminatory language) and ‘sabetsu hyōgen’ (linguistic stereotyping, not necessarily involving any use of contested terms but presenting a particular group of people in an unfavourable light). None of these now common terms is defined in either the 1955 or 1976 editions of Japan’s premier monolingual dictionary, the Kōjien. They came to prominence with the rise of minority group language protests of various kinds in the 1970s and 1980s. The BLL, who will be discussed in detail in Chapter 3, had been active in protesting the use of ‘sabetsugo’ since the 1920s and were the prime movers of the postwar campaigns against linguistic stereotyping through a strategy of vocal denunciation of offenders. Influenced by their evident successes and in many cases actively supported by the BLL, others found their voices during the postwar period, in particular the 1970s and 1980s, as we shall see. But first, a look at the issues involved.

Linguistic stereotyping and social identity

We construct identities in large part by assigning to ourselves and to others labels which shape our concepts of who and what we or they are. When we label ourselves (or others), the agency is ours and the results (usually) satisfy us. When the agency rests with someone else, the experience may be different. The label might be one with which we are happy to concur; on the other hand, it could be a label we consider demeans and diminishes us. When labels of this latter kind are assigned, the name often focuses on some variation from what is considered the social norm: sexual orientation, perhaps, or race/ethnicity or physical appearance. The intent is to hurt or to dismiss, either actively by hurling an epithet or a stereotype at the intended mark or by perpetuating a casual unthinking slur long ingrained through habit. Not even the youngest child in a playground believes the old saw about ‘sticks and stones may break my bones, but names will never hurt me’.

Assigning labels to others plays a significant contrapuntal role in building our own concepts of self. By defining others as what we are not, we emphasize what it is that we think we are, at both personal and social level, often without actually spelling it out. When a society apportions particular names to certain of its members, it reinforces its own belief in what kind of society it is through highlighting in language what it sees as the roles of those members in relation to the whole. This usually serves to label minority groups in such a way as to mark them out as undesirably different from the mainstream:

Labeling traditions imprison users of language in conventional categories that tend to disallow racial and cultural mixing, to nourish obsessions with purity, and otherwise to help condition visceral ambivalencies about belonging to a disparaged group. Traditional ethnic labels thus discourage the formation of attitudes free of the need to resolve real or fictitious multiple identities into one favored identity.

(Wetherall 1981: 290)

Using negative terms is one way to constitute an undesirable Other. Closely related is defining by exclusion: mainstream society decides the names for ‘outsiders within’ (Valentine 1998: 3.3), thereby defining by exclusion what is included. In Japan, the nature of mainstream identity is very clearly spelled out in the essentialist Nihonjinron literature (theories of what it means to be Japanese) which has been an influential publishing genre since at least the 1960s. Succinctly put, a ‘real’ Japanese belongs to the group – i.e. is the same as everybody else in race, language, ethnicity, physical characteristics and cultural heritage. Japan is claimed to be a homogeneous and harmonious society, a construct which leaves very little room for toleration of difference and in effect often denies the existence of marginalized groups. In 2004, acceptance of the idea of multiculturalism appears to be slowly growing in some quarters as a result of the social activism of marginalized groups since the 1980s around the world and of the 1990s’ influx of foreign workers. While ethnic diversity is recognized among immigrants, however, the host society is still very much seen as homogeneous. The ‘uchi’ (insider)/ ‘soto’ (outsider) dichotomy remains alive and well; public discourse about ‘insiders’ – i.e. in this instance the Japanese people themselves – gives little or no recognition of internal diversity.

If we look at Japan’s ‘outsiders within’, we see that by that process of exclusion the mainstream Japanese is not Burakumin, not Ainu, not of non-Japanese ethnicity, not female, not physically or mentally disabled in any way, and not gay. In other words, he is Japanese of a recognized status and occupation, male, heterosexual, and in good mental and physical health. No marginality here to challenge or cause unease through difference. The reality, however, is quite different. Sugimoto (2003: 1), analysing relevant statistics, concluded that a ‘typical’ Japanese (i.e. most representative of trends in today’s Japan) would be ‘a female, non-unionized and non-permanent employee in a small business without university education’. Mainstream identity itself is in reality as diverse as minority identity. ‘Identities of minorities are never unified and can exist only in unstable, debatable form within its vaguely determined boundaries vis-à-vis the majority. By the same token, identity of the so-called majority is never stable or single: the constitution of majority-ness is often as contested as that of minority-ness’ (Ryang 1997: 245).

Sugimoto’s findings are certainly not reflected in the language, where the structures of historical inequality, patriarchy and racism can clearly be seen. The stereotyped representations of members of minority groups and the language used to indicate their exclusion are intimately involved with the maintenance of the carefully constructed national identity. Narramore (1997: 42) notes that in Japan’s handling of key regional issues, ‘the state shows a persistent concern to preserve an homogeneous construction of Japanese identity . . . at a domestic political level this is likely to predominate over a politics of rights’. Where a politics of rights is operational within Japan, he suggests, ‘it reinforces an homogeneous construction of Japanese identity’.

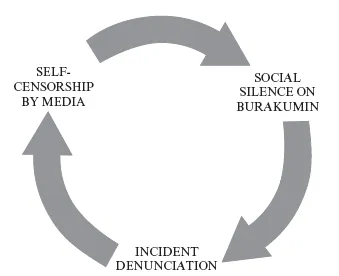

We can see this in action in a roundabout way in the effect of the BLL’s language protest activities. So effective has been the self-censorship practised by mainstream print and visual media in referring to Burakumin as a result of public denunciations that there is now virtual silence on the topic rather than the wider but more fairly nuanced discussion on discrimination the BLL had hoped to stimulate. The model runs thus: tacitly agreed social silence surrounds Burakumin; someone makes a derogatory reference (not necessarily always referring to Burakumin directly, but involving perhaps a metaphorical comparison); the group carries out a denunciation resulting (most times) in retraction; the silence is then reinforced by media self-censorship for fear of further embarrassment (see Figure 1.1). Result: the homogeneous model of state identity remains untroubled by public reference to uncomfortable realities and acknowledgement of difference. In this respect, then, the confrontational tactics have been counterproductive.

Figure 1.1 The circular model of Burakumin protest and its effects.

Language and discrimination: the nexus

Who decides, and on what grounds, whether a term is discriminatory? The answer is clearly those at whom the slur is aimed. To those who have not been the butt of linguistic slurs such decisions may at times seem arbitrary, absurd or rooted in historical events since laundered by time. Letters to newspaper editors often voice reactions of this kind: those who complain about derogatory terms ‘can’t take a joke’, ‘have no sense of humour’ or need to ‘get a life’. Decisions on whether certain language can be regarded as discriminatory are of course made at personal as well as political or corporate levels, with as many views on the subject as there are activists. Power is always a significant factor in the equation. On the one hand, those who use the disputed terms about others wield power – or think they do – over the sense of self and public image of the others through a politics of exclusion and/or denigration. On the other, those who decide that certain words, phrases or stereotypical depictions are discriminatory and therefore should not be used in public discourse exercise power over the language of public life to a certain extent. Agency remains the key.

Arguments about language often hinge on the twin pillars of intent and humour. For every person who argues that a word or phrase is discriminatory, another will retort that it depends on what the person using it intended – perhaps they were unaware that it was a contested term – or that it was ‘only a joke’. The humour argument is often heard in Australia and the United Kingdom and, to a lesser extent, the United States. In Australia, normal social discourse in some sections of the community involves making offensive comments to someone in a sardonic way not intended to be taken literally, with ‘can’t you take a joke?’ a common response to a recipient who protests. A recent instance which illustrates this use of ‘pejorative endearments’ occurred in 2003 over the name of the E.S. ‘Nigger’ Brown football stand at the Toowoomba Sports Ground in Queensland. It may seem impossible to argue for circumstances in which the word ‘nigger’ is used by white people without intent to demean. The stance taken by the TSG Trust members, however, was that the particular 1920s sportsman and later civic leader after whom the stand is named was nicknamed ‘nigger’ because of his fair colouring, with the same ironic sense of humour seen in Virgin Blue’s decision to fly red planes on Australian routes (‘blue’ being a nickname often given to red-haired men). The term dated from that period, they argued, and involves no disrespect to indigenous people. Certain indigenous people living in the area, however, disagreed. Aboriginal activist Stephen Hagan took a complaint to the UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (UNCERD). The Australian government’s stance on the matter was that the context in which the nickname was given and is now used on the stand’s signage rendered the word ‘nigger’ inoffensive. UNCERD disagreed and backed Hagan’s view, to no avail.

This is not a factor in Japan. The BLL has decided that in the case of their own equivalent to ‘nigger’, the word ‘eta’ (sneeringly used to describe their ancestors in the pre-modern period and later, and written with two characters meaning ‘great filth’), there are no circumstances which would render the use of this word permissible. Kaneko, taking issue with the use of out of date discriminatory terms in western scholarship on Japan, reflects that a western scholar’s use of the word ‘eta’ to describe people in modern Japan is akin to using ‘nigger’ as a ‘scholarly term’ to refer to the Afro-American population in the United States today (1981: 117). Not only that particular term, but all words reflecting in any way poorly on members of Burakumin communities come under the same umbrella.

The language of discrimination cannot, of course, be considered in isolation from its social context. We cannot disaggregate it from the structures of discrimination, neglect and ostracism which it both reflects and constitutes. Doyle (1998: 150–1), speaking of sexist language but in an argument that can equally well be applied to any kind of derogatory language, sums up the two views on this aspect of language:

Many people believe that discrimination in society will not change simply by ridding our language of sexism. In this view, using non-sexist language is only paying lip-service to reform rather than addressing the very real problems of sexism in society, including discrimination, harassment, violence against women, and economic inequality. Furthermore, in this view, efforts to adopt non-sexist language can be harmful because they can provide a superficially progressive veneer for an organisation while masking its systemic sexism. Others believe that using non-sexist language is an essential part of tackling societal sexism. In this view, language influences our attitudes and behaviour; watching our language goes hand in hand with being careful how we treat others.

‘Watching our language’ extends in some countries to legislature that makes racial vilification a punishable offence (e.g. Australia’s Racial Hatred Act of 1995). Other countries have no such legislation, although redress for personal slander is possible through their defamation laws. Does the lack of a specific law relating to racial vilification send a message that individual freedom of speech takes precedence over an individual’s right not to be vilified? Japan has no laws of this kind, despite the urging of UNCERD. Freedom of expression, as provided for in Article 21 of the Constitution, is the major sticking point to Japan’s acting on Article 4 of the UNCERD convention (1969, acceded to by Japan in 1996), which stipulates the enactment of legislation outlawing dissemination of racially discriminatory ideas and racially discriminatory acts. The government’s position is that Japan will ‘fulfil obligations stipulated in article 4 of the Convention so long as they do not contradict the guarantees of the Constitution of Japan’; ‘to control all such practices with criminal laws and regulations beyond the current legal system is likely to be contrary to the freedom of expression and other freedoms guaranteed by the Constitution’ (CERD 2000a: paragraph 74).

Article 4 of UNCERD states that:

States Parties condemn all propaganda and all organizations which are based on ideas or theories of superiority of one race or group of persons of one colour or ethnic origin, or which attempt to justify or promote racial hatred and discrimination in any form, and undertake to adopt immediate and positive measures designed to eradicate all incitement to, or acts of, such discrimination and, to this end, with due regard to the principles embodied in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the rights expressly set forth in article 5 of this Convention, inter alia:

- Shall declare an offence punishable by law [my italics] all dissemination of ideas based on racial superiority or hatred, incitement to racial discrimination, as well as all acts of violence or incitement to such acts against any race or group of persons of another colour or ethnic origin, and also the provision of any assistance to racist activities, including the financing thereof;

- Shall declare illegal and prohibit organizations, and also organized and all other propaganda activities, which promote and incite racial discrimination, and shall recognize participation in such organizations or activities as an offence punishable by law;

- Shall not permit public authorities or public institutions, national or local, to promote or incite racial discrimination.

(Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights 1969)

Japan’s periodic reports to CERD, the Convention’s monitoring body, have been criticized for the failure to enact the law required by Article 4. Japan’s first and second periodic reports, for example, submitted together in 1999, argued that Article 14 of its Constitution (‘all of the people are equal under the law and there shall be no discrimination in political, economic or social relations because of race, creed, sex, social status or family origin’) is sufficient to guarantee equality before the law without enacting a racial discrimination law which would conflict with freedom of expression. Pointing out that other avenues existed under the Penal Code for punishing various consequences of discriminatory conduct, the report summed up the Japanese position thus:

The Government believes that respect of human rights by the general public should be essentially enhanced through free speech guaranteed by the right to freedom of expression, and that it is most appropriate that a society itself eliminate any existing discrimination and prejudice of its own will by respecting the constitutional provision prohibiting the abuse of freedom and rights. It is hoped that public relations activities conducted by the Government will facilitate such a self-cleansing action in the society.

(CERD 2000a: paragraph 75)

Then follows a long description of the sorts of ‘educational’ activities instituted by officers of the Civil Liberties Bureau of the Ministry of Justice following a rash of incidents of harassment of Korean students in 1998; a description of the organizational structure for protecting human rights through investigation and education (but only if the offender agrees to participate); and a couple of examples involving...