1 International organizations and implementation

Pieces of the puzzle

Jutta Joachim, Bob Reinalda and Bertjan Verbeek

1 International organizations and policy implementation

International organizations (IOs) nowadays seem ubiquitous. It is hard to imagine any policy domain at the international level in which IOs are not involved in some way or other. The growing importance of IOs in global governance, which is related to the rise of globalization and the end of the Cold War, has prompted students of international relations to reflect once again on their status. Rather than perceiving IOs merely as extensions of states or arenas in which to build winning coalitions, scholars increasingly view them as actors in their own right which play an ever more salient role in global politics than previously envisioned (e.g. Barnett and Finnemore 1999, 2004; Dijkzeul and Beigbeder 2003). As recent studies have aptly demonstrated, IOs can be agenda setters (e.g. Pollack 1997; Reinalda and Verbeek 1998), adjudicators (Alter 2001) and teachers (Finnemore 1996) and can affect decision-making processes (Reinalda and Verbeek 2004).

This edited volume builds on the growing body of literature which works on the assumption that rather than merely being the instruments of states, IOs can influence the course of international events. It seeks to determine the role of IOs in implementation processes and explores the following questions:

- What resources do IOs have at their disposal to ensure that states follow through on their international commitments, and how effective are these?

- How do domestic institutions, actors and political processes impede or facilitate the efforts of IOs?

Why study the role of IOs in implementation? First, states are increasingly delegating the implementation of international agreements and policies to IOs (Hawkins et al. 2006). The World Trade Organization (WTO), for example, has become a major player in interpreting and ensuring compliance with its rules. IOs, such as the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) or the World Health Organization (WHO), are engaged in missions throughout the world, delivering food to those in need, preventing the spread of diseases or providing shelter. The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and the United Nations (UN) are monitoring and administering peace agreements in Kosovo and the Democratic Republic of Congo. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD, also known as World Bank), meanwhile, has launched an anti-corruption campaign and closely monitors both the preparation and the implementation of development-aid projects in recipient countries.

Second, despite the growing involvement of IOs in implementation, we still know very little about how they do their job, what instruments they have at their disposal and which of them they use to ensure that states take action to meet their global commitments. Most of our insights stem from studies on the European Union (EU) (e.g. Knill and Lenschow 2000; Börzel 2001; Falkner et al. 2005) which examine the likelihood of member states to comply with Community directives or regulations (see Mastenbroek 2005 for an overview). While these enquiries provide a valuable starting point for generating hypotheses and a baseline for comparison, they are of limited applicability. Given that the EU is the most institutionalized organization to date and equipped with exceptionally strong enforcement powers (Zürn and Joerges 2005), including legal and financial penalties, findings regarding its role in implementation cannot easily be generalized to include other more conventional IOs, which do not possess such tools. In addition to research on the EU, implementation has also figured in the literature on environmental regimes (e.g. Victor et al. 1998; Young et al. 1999). However, scholars have been much more interested in the effectiveness and problem-solving capacity of such regimes (Zürn and Joerges 2005), as opposed to examining how international agreements are translated into domestic-level policies and what specific role IOs play in this process.

Third, partly owing to the paucity of empirical research, there is an ongoing debate among scholars as to how to ensure compliance with international agreements. While some suggest that enforcement is the only way to prevent states from reneging on internationally agreed commitments (Downs et al. 1996), others, by contrast, argue that a managerial approach consisting of knowledge transfer and financial assistance will yield more satisfactory results (Chayes and Chayes 1993, 1995). These two approaches have hitherto been viewed as mutually exclusive, so that it was either the iron fist – enforcement – or the velvet glove – management – that were assumed to prompt states to take certain actions. Recently, a third perspective has been developed which stresses IOs’ less tangible resources, such as their authority and legitimacy (e.g. Barnett and Finnemore 1999, 2004). Yet, similarly to the previous two, we still know little about its scope conditions, that is, how and when these resources matter.

This volume aims at a better understanding of the role IOs play in implementation by comparing a broad range of organizations in a variety of policy areas. It is the third in a series of books about IOs in a changing global environment. The first investigated the autonomy of IOs (Reinalda and Verbeek 1998); the second examined decision making within them (Reinalda and Verbeek 2004). The findings of the current volume are revealing in several respects. The case studies show that IOs not only use the resources at their disposal in a more flexible way than the literature suggests, but that IOs which lack strong enforcement tools are not necessarily any less effective than those which have these at their disposal. Furthermore, the case studies also suggest that the normative power of IOs plays a far more important role than previously assumed. Regarding domestic-level factors, we find that while deeply entrenched domestic institutions and the opposition of powerful societal or state actors can frustrate the work of IOs, they do not necessarily paralyse them.

In this introduction, we will ‘set the table’ for the subsequent chapters. Section 2 discusses the concept of implementation, distinguishing it from effectiveness and compliance. Drawing on different international relations approaches, in Section 3, we will identify and discuss two major factors in the literature which may empower or restrict IOs in implementation:

- the resources of IOs

- domestic-level factors.

While the former include both enforcement measures, such as monitoring and sanctioning, and softer instruments, such as managerial skills or authority, the latter include the nature of political systems (especially mature versus new democratic states), domestic institutions and the power of societal groups, bureaucracies or civil services. Finally, Section 4 offers an overview of this volume.

2 Defining implementation

Traditionally, implementation has been the subject of policy and legal studies as well as public administration. Research on this subject flourished during the 1970s and 1980s but came to a halt during the last decade. Reflecting on the very latest research on implementation, Saetren (2005) lists a number of reasons for the declining interest in implementation, including:

- a protracted debate about the top-down and bottom-up approaches – that is, whether to examine the agency or bureaucracy in charge of it or whether to pay closer attention to the political process and/or societal effects which it brings about;

- an alleged selection bias towards cases involving implementation failure;

- growing doubts among scholars about the extent to which the policy process could be neatly segmented into discrete stages that progressed sequentially from agenda setting, through adoption, implementation and subsequent policy phases.

While many policy scholars already began to characterize implementation as ‘yesterday’s issue’ (Hill 1997), ‘out-of-fashion’ or even ‘dead’ (Saetren 2005), there has been a renewed interest in the subject in recent years. One change has been, however, that students of international relations and comparative politics have joined the debate (e.g. Falkner et al. 2005; Zürn and Joerges 2005). This trend may be explained, on the one hand, by the growing number of international agreements and, on the other hand, by the debate about whether, when and how these agreements matter.

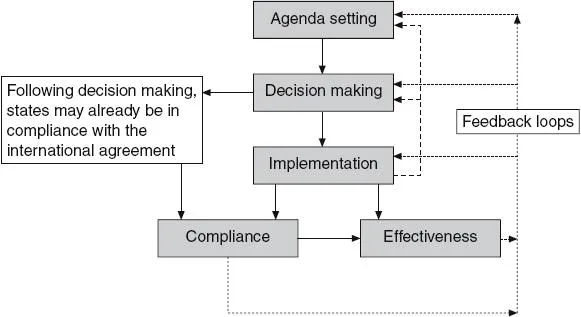

Broadly defined, implementation refers to the translation of agreed-upon international agreements into concrete policies and manifests itself in the adoption of rules or regulations, the passage of legislation or the creation of institutions (both domestic and international) (Victor et al. 1998: 4). Although often used interchangeably, implementation differs from compliance and effectiveness (see Figure 1.1). Unlike compliance, which asks whether ‘the actual behaviour of a given subject conforms to prescribed behaviour’ (Young 1979: 3; Simmons 1998: 78; Victor 1998; Victor et al. 1998), implementation pays close attention to the concrete actions which state officials take (or fail to take) to meet international agreements. Effectiveness, by contrast, is concerned with the impact of internationally agreed-upon policies and varyingly defined as the degree to which a rule induces changes in behaviour that promote the underlying objectives of the rule, the degree to which it improves the state of the underlying problem or the degree to which it achieves its policy objectives (Keohane et al. 1993: 7; Young 1994: 140–62; Young et al. 1999). Although they are distinct concepts, compliance, effectiveness and implementation are not entirely unrelated. For states to be either in line with international agreements or for these agreements to be consequential, passing a law or establishing new institutions may be a critical and necessary step (Raustiala and Slaughter 2001: 539). By the same token, a lack of effectiveness or compliance may require responsible actors to do more in terms of implementation.

Whereas compliance and effectiveness are static notions that refer to the nature of policies at a specific moment, implementation is a much more dynamic phenomenon, because it presupposes the mobilization of resources on the part of the various actors involved. These actors include IOs, to which states may have delegated elements of implementation. For example, IOs may have been tasked with monitoring and reporting on the actions that the responsible national actors are supposed to take, or they may have been asked to assist governments actively in meeting their international commitments by delivering certain resources. Less frequently, IOs themselves are entirely in charge of implementation, but even in these cases, governments still remain crucial actors, because implementation ‘on the ground’ depends on facilities that only national (or even local) authorities can provide (see e.g. Caplan 2005).

Figure 1.1 Implementation as part of the policy cycle.

In addition to IOs, other actors may play a role in the implementation process. Other international actors may become engaged, such as nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), other intergovernmental organizations or their specialized bodies that are also active in the specific field. Nationally, governmental agencies, political parties, NGOs, interest groups or the media may have a stake in specific policy outcomes or have special resources at their disposal, and therefore they too may become part of implementation. As the subsequent chapters illustrate, these actors may impede, or facilitate, the work of IOs.

For analytical reasons, in this volume, we treat implementation as a distinct phase of the policy cycle, which requires the mobilization of resources. We assume that implementation follows the adoption of an international agreement and may or may not bring a state into compliance with that agreement. Implementation may have both intended and unintended effects depending on what measures are taken, or resisted, by responsible parties at the domestic level. Nevertheless, we are aware that, empirically, policy making is more complex and recursive, so that implementation as a phase cannot be clearly separated from other phases of the policy cycle. Two observations help to illustrate this point. First, apart from national efforts to meet international commitments, implementation may also evolve into what Puchala (1975: 496) once referred to as ‘post-decisional politics’ – that is, an opportunity for actors to revive political battles already fought in earlier phases of the policy cycle (see also Hill and Hupe 2002: 8). In particular, implementation may be used by individual actors who had been dissatisfied with the internationally adopted policy to alter its content and therefore pose a challenge for satisfied actors to ensure that the agreed-upon policies are carried out as agreed (Hill 1997: 381; see Falkner et al. 2004 for a more sceptical assessment of whether ‘post-decisional politics’ in fact takes place). Second, implementation may also set in motion feedback loops. For example, an international agreement which has been adopted may subsequently be revised and altered due to uncertainties as to how individual articles are to be understood. This may occur as a result of difficulties that were encountered during national implementation, because of new information that has become available or because of changes in the broader context. In short, and as Figure 1.1 illustrates, the lines between implementation, decision making and agenda setting, on the one hand, and implementation, compliance and effectiveness, on the other hand, may in practice be much more blurred and interconnected than can be accounted for in this volume. A lack of effectiveness or insufficient compliance may require actors to take additional action at the domestic level (implementation) and prompt them to propose a new agreement (agenda setting) or to make amendments to the existing one (decision making). Kingdon’s (1984) notion of various simultaneously operating policy ‘streams’ may, therefore, be more appropriate than ...