1 An introduction to tourism and global environmental change

Stefan Gössling and C. Michael Hall

Introduction

Tourism is largely dependent on natural resources. For example, the provision of fresh water for drinking, taking showers, swimming pools or the irrigation of hotel gardens seem self-evident preconditions for tourism all around the world. Beaches and coastlines, mountains, forests, lakes, oceans and the scenery provided by landscapes containing these elements are central to the attraction potential of most destinations. Similarly, biodiversity is a tourist magnet in many regions, including a wide variety of bird and fish species, as well as charismatic mammals such as moose or deer, whales, dolphins or the ‘big five’ (leopard, lion, rhino, elephant, hippopotamus) in national parks in eastern and southern Africa. In mountainous areas, snow cover is a conditio sine qua non for winter sports, including skiing, snowboarding, snowmobiling and dog sledding, and many areas would lose their tourist appeal without snow – for instance, what would impressive mountain ranges like the Alps or tropical Mount Kilimanjaro be without their white-covered tops? Clearly, most tourism is based on stable and, for tourism, favourable environmental conditions.

Global environmental change (GEC) threatens these very foundations of tourism through climate change, modifications of global biogeochemical cycles, land alteration, the loss of non-renewable resources, unsustainable use of renewable resources and gross reductions in biodiversity. Elements of the global environment are always changing although change is never uniform across time and space. Nevertheless, ‘all changes are ultimately connected with one another through physical and social processes alike’ (Meyer and Turner 1995: 304). The scale and rate of change has increased dramatically because of human actions within which tourism is deeply embedded.

Human impacts on the environment can have a global character in two ways. First, ‘global refers to the spatial scale or functioning of a system’ (Turner et al. 1990: 15). Here, the climate and the oceans have the characteristic of a global system and both influence and are influenced by tourism production and consumption. A second kind of GEC occurs if a change ‘occurs on a worldwide scale, or represents a significant fraction of the total environmental phenomenon or global resource’ (Turner et al. 1990: 15–16). Tourism is significant for both types of change.

This volume takes a systematic approach to understanding the environmental, social, economic and political interrelationships of tourism and GEC. In the first section, environmental change in each of the environments of importance for tourism is analysed, including the polar regions, mountains, lakes and streams, forests, coastal zones, islands and reefs, deserts and savannah regions, as well as urban environments. The volume’s second section focuses on four aspects of GEC that might become particularly important for tourism: availability of fresh water, existence of diseases, biodiversity, and frequency and intensity of extreme weather events. In the final section, the book discusses issues of adaptation to GEC. Although this is a relatively unexplored research field of great uncertainty, the contributors present options for tourism adaptation in those environments that are likely to face the most rapid environmental changes – mountains – and presents a number of new avenues to the discussion of the consequences of GEC for tourism from sociology and business perspectives.

Tourism development

Any adequate conceptualisation of tourism demands a comprehensive approach that involves the relationships between tourism, leisure and other social practices and behaviours related to human movement (Coles et al. 2004; 2005). Such an assessment is necessary in the analysis of contemporary human mobility given the extent to which time-space convergence has made it easier for those with sufficient time and economic budgets to move over time and space. Travel which once took two or three days to accomplish may now be completed as a daytrip. Convergence through physical travel is also complemented by convergence in communications (Janelle and Hodge 2000). Clearly, such shifts in mobility have implications for a wide range of human activities both within and outside of tourism. They can be seen alongside ideas of accessibility, extensibility, distance and proximity, significant elements of global socio-cultural change (Johnston et al. 1995), as well as underlying social contributions to tourism related consumption of the environment (Hall 2005a).

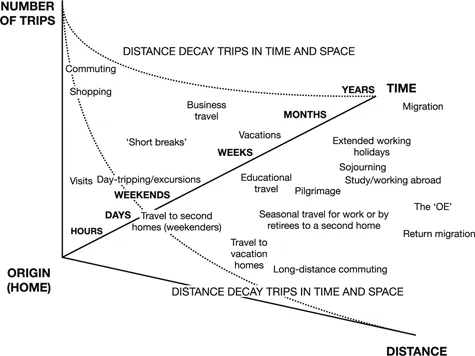

The relative lack of interplay and cross-fertilisation between the fields that study human mobility is remarkable (Williams and Hall 2002). This is especially evidenced by the difficulties to be encountered in finding overlap between national and international surveys of tourism and migration, and studies of short- and long-term travel undertaken in transport studies, a factor that also has considerable impact on the understanding of the contribution of tourism to GEC. Nevertheless, as Coles et al. (2004) argued, the conceptualisation and development of theoretical approaches to tourism should consider the relationships of tourism to other forms of mobility, including the creation of extended transnational networks that also promote human movement. Figure 1.1 presents a model for describing different forms of temporary mobility in terms of three dimensions of space, time and number of trips. The fact that the number of movements declines the further one travels in time and space away from the point of origin is well recognised in the study of spatial interaction. However, it has not been used as a means to illustrate the totality of trips that are undertaken by individuals.

Figure 1.1 Extent of mobility in time and space

Source: after Hall 2003

The relationship represented in Figure 1.1 holds whether one is describing the totality of movements of an individual over their life span from a central point (home), or whether one is describing the total characteristics of a population (Hall 2005a; 2005b). The figure illustrates the relationship between tourism and other forms of temporary mobility including various forms of what is often regarded as migration or temporary migration (Bell and Ward 2000). Such activities, which have increasingly come to be discussed in the tourism literature, include travel for work and international or ‘overseas’ experiences (e.g. Rosenkopf and Almeida 2003), education (e.g. Field 1999), health (e.g. Goodrich 1994), as well as travel to second homes (e.g. Hall and Müller 2004), return migration (e.g. Duval 2003) and diaspora (e.g. Coles and Timothy 2004). Arguably, some of these categories could be described as ‘partial tourists’ (Cohen 1974), or even as ‘partial migrants’, although the amenity or leisure dimension remains important as a motivating factor in their voluntary mobility (Frändberg 1998; Coles et al. 2004; Hall 2005a).

Focusing on the range of mobilities also provides an important dimension with respect to the examination of tourism’s impacts. Mobilities need to be examined over the duration of the lifecourse, so that the linkages and relationships between different forms of ‘temporary’ and ‘permanent’ mobilities, particularly tourism and amenity migration, are better understood. Such a lifecourse approach may also have extremely practical applications in terms of studying how people switch modes of consumption between locations and activities. For example, while people may attempt to be green consumers in one aspect of their life, their consumption may actually increase in others, thereby leading to no net improvement in their overall rate of consumption.

Most research on tourism impacts has also tended to occur at the destination (Lew et al. 2004). This has meant that research has often examined local factors rather than the totality of the impact of tourism in time and space by also considering effects at the tourism-generating region, and travel to and from destinations. As significant as destination impacts might be, the study of tourism impacts therefore needs to be undertaken over the totality of the tourism consumption and production system, rather than just at the destination (Bach and Gößling 1996; Frändberg 1998; Høyer 2000; Gössling 2002; Frändberg and Vilhelmson 2003; Hall and Higham 2005).

Consideration of the total movement of humans in time and space is important because the extent of space-time compression that has occurred for many people in the developed world has led to fundamental changes in individual mobility and in assumptions about personal mobility in recent years. Travel time budgets have not changed substantially but the ability to travel further at a lower per unit cost within a given time budget has led to a new series of social interactions and patterns of production and consumption (Schafer 2000). For many people leisure mobility is now routine. Advances in transport and communication technology that have been adopted by a substantial, relatively affluent, proportion of the population enable such people to travel long distances to satisfy demands for amenities – what one would usually describe as tourism. Indeed, Hall (2005a) has argued that one interpretation of this perspective is that the study of tourism is intrinsically the study of the mobile consumption patterns of the wealthier members of society.

The means of transport used in international tourism changed fundamentally with the rise of civil aviation in the 1960s. From being an option only for wealthy tourists in the 1960s and 1970s, aviation soon became one of the most popular means of transport in international travel, with growth rates in the order of 5–6 per cent per year from 1970 to 1993, and 7.1–7.8 per cent per year from 1994 to1996. Some 40 per cent of all international tourist arrivals might now be by air (Gössling 2000). At the end of 2002, airlines were actively operating some 10,789 passenger jets with 100 seats or more, representing a total of 1.9 million installed seats.

Boeing (2003) and Airbus (2003) predict that air travel will continue to grow rapidly, with average annual growth rates of 5.0–5.2 per cent to 2022/23. By 2022, the number of aircraft is predicted to increase by 90 per cent to about 20,500, while the number of installed seats will more than double to reach 4.5 million (Airbus 2003). Boeing (2003) also predicts that competition for markets will be strong, leading to more airline entrants, lower fares and improved networks. Simultaneously, it is anticipated that governments will continue to deregulate air travel markets. Consequently, air travel is one of the key factors in international tourism development, outpacing growth in surface-bound means of transport.

Two other aspects of air travel deserve mention in the context of tourism and GEC. First, flight distances are predicted to increase, with the average distance flown growing from 1,437km in 2002 to 1,516km in 2022 (Airbus 2003). Second, a large proportion of the current fleet of aircraft (60 per cent) will still be in operation 20 years from now (Boeing 2003), indicating long operation times for aircraft and concomitant high fuel use for older models still in use. The estimated scale of international tourism growth, as well as the enthusiasm from the tourism industry that seemingly accompanies such growth, is well illustrated in the World Tourism Organization’s (WTO) 2020 vision:

By the year 2020, tourists will have conquered every part of the globe as well as engaging in low orbit space tours, and maybe moon tours. The Tourism 2020 Vision study forecasts that the number of international arrivals worldwide will increase to almost 1.6 billion in 2020. This is 2.5 times the volume recorded in the late 1990s … Although the pace of growth will slow down to a forecast average 4 per cent a year – which signifies a doubling in 18 years, there are no signs at all of an end to the rapid expansion of tourism … Despite the great volumes of tourism forecast for 2020, it is important to recognise that international tourism still has much potential to exploit … the proportion of the world’s population engaged in international tourism is calculated at just 3.5 per cent.

(WTO 2001: 9, 10)

Whether such rates of growth are possible is debatable given the potential impacts of future increased fuel prices or ‘wildcard’ events such as an economic or political crisis, such as occurred in Asia in 1997/98 (Hall 2005a). However, the broader and probably more important debate, as to whether such rates of growth are sustainable or even desirable given the potential environmental effects of such growth, is not really being fully entered into in the academic field and certainly not by leading tourism bodies such as the WTO and the World Travel and Tourism Council (WTTC). For example, the Blueprint for New Tourism published by the WTTC in 2003 does not even acknowledge the potential relationships between tourism and global climate and environmental change. The WTO has recently described the interaction of tourism and climate change as a ‘two-way relationship’ (WTO 2003), but there is no official document, as yet, dealing with this problematic interaction. Quite the contrary, the WTO’s STEP programme (WTO 2005) fully ignores the environmental consequences of leisure transport.

Global environmental change

There is comprehensive evidence for GEC caused by human activities: land-use changes, altered biogeochemical cycles, climate change, biotic exchange, as well as disturbance regimes (e.g. tropical storms) have been described in a wide range of publications (Klein Goldewijk 2001, Sala et al. 2000, IPCC 2001, Loh and Wackernagel 2004). GEC will have complex consequences for ecosystems, as well as for social and economic systems. Biodiversity will mostly be affected by land-use changes, followed by climate change (increasing temperatures), nitrogen deposition, biotic exchange and atmospheric CO2 concentration increases (Sala et al. 2000). Note, however, that different biomes will be affected to varying degrees by these changes – for example, Arctic environments will mostly suffer from increasing temperatures (ACIA 2004). Global environmental change will also affect human social and economic systems though increasing temperatures, sea-level rise, changing precipitation patterns and weather extremes, which in turn will cause other environmental changes, such as new disease frontiers, coastal erosion and new patterns of urbanization and mobility. We shall now discuss the observed and predicted patterns of some key parameters of GEC.

Temperature increase

Global average surface temperatures, the average of near-surface air temperature over land and sea surface temperature, are changing. As documented by the Intergovernmental Panel of Climate Change (IPCC) – a scientific body created in 1988 by the World Meteorological Organization and the United Nations Environmental Programme – global average surface temperatures have increased by 0.6 ± 0.2°C over the twentieth century (IPCC 2001). Globally, the IPCC anticipates that the 1990s were the warmest decade and 1998 the warmest year since 1861, when temperature measurements were introduced.

There is even more evidence for ongoing climate change. For example, since the late 1950s, when weather balloons were introduced, global temperature increases in the lowest 8km of the atmosphere and in surfa...