- 364 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Stained Glass in England During the Middle Ages

About this book

First published in 1993. The first modern study of the medium, this book considers stained glass in relation to architecture and other arts, and by examining contemporary documents, it throws valuable light on workshop organisation, prices and patronage.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Stained Glass in England During the Middle Ages by Richard Marks in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Donors, Technique, Iconography, Domestic Glass

1

Donors and Patrons

General surveys of medieval stained glass have tended to open with a chapter or section on the technical aspects of the craft.1 As almost every window was executed to the specific commission of those paying for the work, be they monarch, prelate, noble, merchant or churchwarden, it is perhaps more logical to begin by examining the various classes of donors and patrons in medieval England, how their generosity was commemorated and how both patron and craftsman ensured that the commission was carried out to their mutual benefit and satisfaction.

Patrons

Information on stained glass patronage before the fourteenth century is as sparse as the surviving glass. The earliest known specific reference is in 675, when Benedict Biscop, Abbot of Monkwearmouth in Tyne and Wear, sent to Gaul for craftsmen to glaze the monastery windows; at about the same time Bishop Wilfrid of York glazed the windows in his Minster.2 Even in these instances it is by no means certain that the individuals in question actually met the cost of the glazing from their own personal financial resources, as opposed to those of the institution. Likewise, there are no indications as to how the sumptuous glazing of the late Anglo-Saxon churches of the Old and New Minsters at Winchester (Pl IV) was financed.3 There is even a dearth of information on the donors of the first surviving major ensemble of glass in England, the late twelfth- and early thirteenth-century glazing of Canterbury Cathedral4 (Pls VI, VII; Figs 92–6) Completely lacking from its windows are any representations of donors such as those which appear in profusion in the contemporary glass of Chartres Cathedral.5 The absence of donor figures may imply that the Canterbury windows were financed by the priory of Christ Church as a corporate body, rather than from individual benefactions.

Something of the kind certainly happened at Exeter (Pl XIII), where in the late thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries the chapter undertook a major reconstruction of the east end of the cathedral, which included the glazing.6 A Fabric Fund was created from substantial annual contributions from successive bishops of the See, yearly donations of a proportion of their salaries by the various cathedral office-holders, and the canons gave a half-share of the income from their prebends. Further sources of income were obtained by the dean and chapter through assigning a small group of annual rents to the Fund, and clerical subsidies within the diocese were raised by the bishops. In addition the rebuilding attracted alms and posthumous bequests from members of the foundation. Similar methods of financing major building and glazing work were adopted in the same period by the chapter of Wells Cathedral (Pl XIV; Figs 63, 118, 122), including the imposition on its own members of a tax of one-tenth of the annual revenue from all prebends;7 the names of a number of canons and other officials which now occur in the Lady Chapel glazing are probably a record of those clergy who contributed to the work.8

The more fortunate religious establishments were relieved of the burden of fund-raising for windows and/or the fabric by having a patron who met the costs from his or her resources. Often these establishments were royal foundations or churches closely associated with the monarchy. To cite one very important example, the costs of the glazing as well as the structure of Westminster Abbey (Pl IX; Figs 5, 102(c), 106), the coronation church and royal mausoleum, were met entirely by Henry III (1216–72).9 He was a prolific builder and there are frequent references to the ordering of stained glass windows in the royal residences in the Liberate Rolls and other accounts during his reign.10 Later sovereigns also commissioned glazing as part of their building projects, both in their palaces and castles and in their religious foundations. Edward III (1327–77) was responsible for the windows in St Stephen’s Chapel (Fig. 129), Westminster, and in the royal chapel at Windsor.11 The Lancastrian and Yorkist monarchs embellished their residences with glazing, and under Henry VIII (1509–47) two of the most prestigious ecclesiastical glazing schemes of the early sixteenth century were carried out, the windows of his father’s great chapel at the east end of Westminster Abbey (Figs 182, 183) and those of Henry VI’s foundation at King’s College (Pls XXVIII, XXIX; Figs 184, 185), Cambridge.12 It is ironic that the reign of the same monarch witnessed the beginnings of a religious reform movement which had as one of its consequences the ending of glass-painting as a major artistic medium.

Fig. 5 WESTMINSTER ABBEY, St Edmund’s Chapel: arms of Cornwall, c. 1254–9.

From the fourteenth century onwards many foundations were established by magnates and prelates, the primary function of which was to pray for their souls. These ranged in size from great dynastic mausolea such as the Yorkist collegiate church at Fotheringhay (Figs 165, 199) in Northamptonshire or the large college at Tattershall (Pls III(c), XXIII: Figs 15, 48, 61) in Lincolnshire endowed by Ralph Cromwell (d. 1456), Lord Treasurer of England, down to more modest chantry chapels.13 One of the most elaborate chantries is the Beauchamp Chapel (Pl III (d); II,Figs 69, 164) attached to St Mary’s church in Warwick and founded by Richard Beauchamp, Earl of Warwick (d. 1439).14 The windows of Tattershall and Warwick were in fact commissioned (and the subject-matter chosen) by the executors of the two founders, a by no means uncommon situation. Establishments such as these could be sumptuously glazed by the leading craftsmen of the time. Thus the windows in the chapels at New College (Figs 141, 144(b)), Oxford, and Winchester College (Pl XIX; Fig. 31(a)) were executed by Thomas Glazier of Oxford in the 1380s and 90s. Both colleges were founded by William of Wykeham, Bishop of Winchester, who also left 500 marks in his will for the glazing of the nave of his cathedral church.15 Wykeham must be considered one of the most important patrons of stained glass in the late Middle Ages.

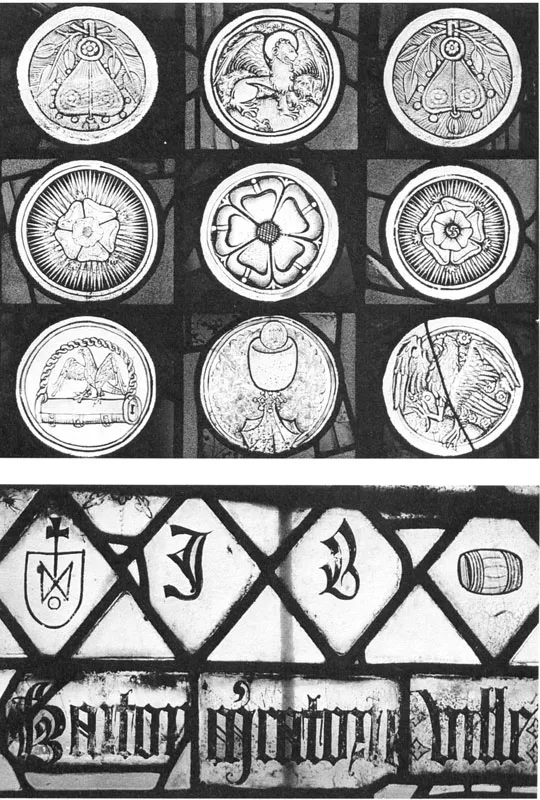

Fig. 15 Badges and devices: (above) TATTERSHALL (Lincs.): roundels with Yorkist and religious devices and the badge of Ralph, Lord Cromwell, c. 1480–2; (below) merchant’s mark, initials and barrel rebus of John Barton (d. 1491) at HOLME-BY-NEWARK (Notts.).

Since the early thirteenth century responsibility for the fabric of parish churches had been divided between the rector (lay or clerical), who looked after the chancel, and the parishioners who had the upkeep of the nave; however, sometimes they were glazed entirely at the expense of a single individual or family, usually the lord of the local manor. In the middle of the fourteenth century the De Fresnes family installed a fine series of windows in the twelfth-century church at Moccas in Hereford & Worcester; 150 years later John Tame and his son Sir Edmund rebuilt and lavishly glazed Fairford (Pls XXVI, XXVII; Figs 178, 179) church, Gloucestershire, using Netherlandish glass-painters.16 On occasions the parochial clergy, who quite frequently appear as donors of windows, paid for the entire reconstruction of their churches; one instance is Thomas Alkham, rector of Southfleet in Kent between 1323 and 1356.17

Institutions which were able to enjoy the support of a royal or other benefactor for an entire scheme were in the minority. In most instances the community looked to donors for individual stained glass windows. By the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, when the evidence becomes more than occasional, patrons , reflected the transformation of English society which was taking place, from the traditional ‘three estates’ (priests, knights and labourers) to a more complex structure which embraced inter alia a rich urban mercantile class. The windows of York Minster nave were glazed between 1291 and c. 1339 by a series of individual donors, including several clerics attached to the Minster, notably Peter de Dene, a canon and vicar-general to Archbishop Greenfield (window nXXIII), and Robert de Riplingham, chancellor of the diocese from 1297 to 1332 (window sXXXI).’18 Most important of all was Archbishop Melton, who in 1338/9 donated 100 marks for the glazing of the great nave west window (wl) (Pl. XVI).19 The lay patrons numbered not only local magnates such as the Percy and Vavasour families (windows N...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Colour Plates

- List of Figures

- Window Notation

- Abbreviations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Part I Donors, Technique, Iconography, Domestic Glass

- Part II Chronological Survey

- Notes

- Select Bibliography

- Index