1 What do people believe about memory and how do they talk about memory?

Svein Magnussen, Tor Endestad, Asher Koriat and Tore Helstrup

Memory is a central part of the brain’s attempt to make sense of experience, and to tell coherent stories about it. These tales are all we have of our past, so they are potent determinants of how we view ourselves and what we do. Yet our stories are built from many ingredients. Snippets of what actually happened, thoughts about what might have happened, and beliefs that guide us as we attempt to remember. Our memories are the powerful but fragile products of what we recall from the past, believe about the present, and imagine about the future.

Schacter, 1996, p. 308

INTRODUCTION

A Norwegian newspaper (Dagbladet, Magasinet, 27 March, 2004) recently told the story of Dodo, a young man of Asian origin who in January 2003 woke up on the freezing ground in a small village in Switzerland with his well-equipped rucksack nearby, stuffed with expensive clothes and a money belt containing $5000, but no identity papers or tickets and with absolutely no personal memory. Dodo wandered around in Europe for some weeks, and somehow managed to travel to Oslo, Norway, for reasons he cannot explain; there he is currently being studied at the University Hospital. His memory loss of the time before he woke up in Switzerland is massive; he has no idea who he is, and he did not recognize his own face in the mirror. He has even lost his native language – he speaks heavily accented English but not any Asian language. All he has is a picture of a young girl, taken in Paris, but he has no idea who she is. Dodo’s memory now goes back roughly a year – the rest is speculation. The only thing he knows about himself is that he smokes Camel and likes pop music. “I was nobody”, Dodo says, “Now I tell myself I was born one year ago”.

The story of Dodo, fanciful as it may seem, illustrates well the central role of memory in human life. This young man has lost not only his personal past – his autobiographical memories – but he has also lost large parts of his general knowledge of the world and even his ability to speak his native language. Thus, the systems or forms of memory that we term episodic and semantic memory are, in Dodo’s case, heavily affected. True, there is more to memory than general knowledge and the recollection of personal episodes, but episodic memory is assigned a special role in human life. Episodic memory is unique in that memories are associated with a place and a time, an association that even if incorrect gives the memories a sense of personal historical truth, and contributes to the person’s self-identity. Episodic memory is, in the words of Tulving (2002), the only known example of a process where the arrow of time is turned back and the past can be re-experienced. While some form of episode-like memory may be demonstrated in non-human primates (Hampton & Schwartz, 2004), genuine episodic memory is probably unique to humans as it may depend upon linguistic capacities. Without episodic memory, the mental representation that psychologists call the self – the organization of personal memories in a historical context – is lost. Apparently this is what has happened to Dodo.

Dodo suffers from the condition of retrograde amnesia. That is, he has lost his memory in the sense people usually use the term memory. When we talk about memory in everyday life we refer to the recollection of private experiences and facts we have learned about the world. But obviously Dodo remembered many things; he remembered what cigarettes were for, the workings of photographic equipment, he understood the value of money, was able to buy food, and mastered the skill of travelling by public transport. So he could make use of many of the things he had learned. This type of selective memory impairment, which has been reported in many patients exhibiting large individual differences in memory profiles, is the main evidence cited by memory researchers in support of the idea that memory, rather than being a single cognitive process or system, is a collective term for a family of neurocognitive systems that store information in different formats (Schacter, Wagner, & Buckner, 2000; Tulving, 2002).

Varieties of human memory

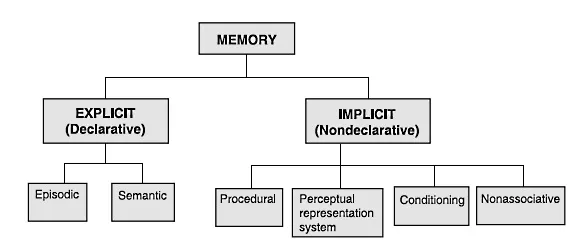

Most current taxonomies of human memory (see Figure 1.1) distinguish between several forms of memory. For example, most memory researchers agree that in addition to episodic-semantic memory, which supports explicit recollection of previous episodes and previously acquired knowledge, there exists another system that allows previous experiences to express themselves directly but implicitly, as for example in skill learning, emotional conditioning and perceptual learning. These distinctions will be further discussed and elaborated in subsequent chapters, and will only briefly be reviewed here.

Motor learning is responsible for all the procedural skills that we have acquired throughout life, from knowing how to eat with a fork and knife (or sticks) to the mastery of swimming, bicycling or driving a car, as well as the advanced skills of playing billiards or playing a saxophone. Memory is implicit in the sense that the effects of previous experiences and exercises manifest themselves directly in behaviour; the individual training sessions may be vaguely remembered or may be completely inaccessible to conscious recollection, but the mastery of the skill is there. In a broad sense, motor skills also include what is referred to as procedures – linguistic as well as academic and social skills.

Figure 1.1 A taxonomy of human memory systems.

Conditioning represents a basic memory system (Squire & Kandel, 1999) that, in humans, is particularly important in tying emotional reactions to external stimuli or situations. For example, in phobic reactions, anxiety is triggered by the phobic stimuli but the person is typically not aware of the learning episodes in which the connection between the emotion and stimulus was established. Similarly, a piece of music, or a specific odour, may evoke romantic feelings without an accompanying experienced memory episode.

Perceptual learning, or the perceptual representation system, enables us to perceive the world as consisting of meaningful entities, because in order to produce a perceptual experience, on-line sensory signals must join stored representations, and this linking is part of the perceptual process itself. To see is to recognize, or to realize that you do not recognize.

We could go on to list a variety of identified memory types or typical memory tasks. One reason why many memory researchers were led to postulate the existence of separate memory systems is that lesions to the brain may impair some forms of memory while leaving other forms intact; such dissociations have been described for several memory systems.

An important feature of the memory-systems concept is the idea that the various systems store information in different formats, and that the information stored in one format is not directly translatable into others. This implies that the information stored in one system is not immediately accessible to other systems. Assuming that the memory systems operate independently and in parallel, this would imply that most experiences are recorded and stored in parallel in different formats, and can be accessed with the assistance of several memory systems working in concert (Tulving, 2002). Memory researchers disagree, however, as to whether the distinction between episodic and semantic memory indeed reflects separate systems or only different manifestations of one and the same system. When memory is tested in the laboratory, it may be difficult to distinguish episodic from semantic memories. Most memories will contain aspects of both. For example, when a particular picture is recognized as having been presented earlier, is it because the participant remembers it or because the participant knows that it was there? In the first case it would be episodic memory, in the second it might be semantic memory that governs the choice – or perhaps it is guessing based on yet another implicit memory system? Tulving and Schacter (1990) identified priming as a separate memory system in implicit memory. In priming, the person’s performance on a specific recognition or production task is facilitated (or inhibited) by the previous presentation of related information.

This idea has also been debated, however. There is little disagreement between memory researchers that human memory covers a vast array of memories of different types, and that some of these can be functionally lost because of failures of systems or processes while others remain intact. There is an ongoing discussion, however, as to whether memory is a set of systems or a set of processes or classes of memory operations (Bowers & Marsolek, 2003; Foster & Jelicic, 1999; Tulving, 2002). The treatment of human memory in everyday contexts in this book is neutral with regard to this debate.

The importance of memory in human life is testified by the widespread public interest in memory-related questions. It is a popular theme in party conversations: Many people wonder about memory either because they notice absentmindedness or forgetfulness in everyday life, or because they have relatives who have become disoriented or have bizarre memory problems. The reliability of memory and eyewitness reports is discussed in the media. Articles on memory-enhancing techniques are frequently published in the press, “therapeutic” groups and techniques for recovering near-birth memories are advertised, and topics such as memory and emotion are among the most popular ones for visits to neuroscience websites (Herculano-Houzel, 2003) – just to mention a few examples. People have various ideas about memory, about how we remember and why we forget, and about ways to improve memory. These ideas are sometimes disclosed in the way we speak about memory – the metaphors of memory. A question of interest is whether the folk psychology of everyday memory constitutes just a set of loose metaphors, or are these metaphors actually based on firm common sense? If the latter is true, then to what extent has modern memory research exchanged old metaphors for new ones, which today are invading everyday memory conceptions? In what follows, we discuss lay beliefs about memory, focusing first on the way people talk about memory, and then looking at the specific ideas people have about memory.

HOW WE TALK ABOUT MEMORY – MEMORY METAPHORS

In attempting to understand memory, scientists as well as laymen are forced to try to describe something that is not directly observable. We are aware of the processes that take place during learning, and of the processes that take place in attempting to search for a piece of information in memory, but we have little access to the processes that mediate between encoding and retrieval. In order to make sense of the phenomena to which we have little access, both laypeople and researchers tend to use metaphors and analogies borrowed from the physical world. The use of metaphors is very widespread in communication: When describing a man’s bravery we might say “he is a lion” or if he is coward, “he is a mouse”. What is physical and known is used to describe what is abstract or unknown. This use of analogies and metaphors is not only characteristic of everyday communication; memory researchers sometimes also resort to metaphors in communicating their ideas. Furthermore, these metaphors also guide them in formulating their questions and designing their experimental paradigms. In his classic article on reaction time research, Saul Sternberg (1969) described a process termed “memory scanning”. In a task used to investigate that process, Sternberg had people study lists of letters or digits and then indicate whether a subsequently presented target letter or digit had been included in the study list. Implicit in the Sternberg paradigm is the notion that a list, represented as a mental image, is processed by something like a beam scanner, a mechanism that searches the image in order to carry out the task of recognition. The scanner metaphor accords with participants’ post-experimental reports of what they did in order to perform the task, and is commonly described by laypeople in terms of the notion of a memory “search”. “Wait a moment; I need to search my memory for that name.”

Metaphors are quite frequent in everyday descriptions of memory. However, as illustrated by the previous example, memory researchers also use metaphors to guide investigations. The metaphor in the Sternberg case is not just an “as if” conceptualization of a phenomenon. By utilizing the metaphor, Sternberg postulated a mechanism that could either operate the scanner or examine the content of memory, but could not do both at the same time. He further assumed that it takes a fixed amount of time to switch from one operation to the other; each step of encoding and matching takes a certain time for each item in the list. If scanning involves searching the list of items one at a time, the pattern of reaction times would be different to that if all items were scanned simultaneously. Thus, the metaphor, when specified, permits scientists to derive testable hypotheses; the metaphor serves as a working model for scientific tests (Fernandez-Duque & Johnson, 1999).

In many cases, the metaphors used by scientists are simply ways to talk about and think about phenomena at a pre-theoretical stage. Many such metaphors have been proposed to guide our understanding of memory. Thus, memory has been compared to a wax tablet, an encyclopaedia, a muscle, a telephone switchboard, a computer and a hologram (Roediger, 1980). Theorists have proposed core-context units, cognitive maps, memory tags, kernels and loops (Underwood, 1972). Common to most memory metaphors, in science and in everyday life, is that they are based on the idea of an organized space; a physical store of some sort. This space might have a structure of networks with nodes or paths or hierarchies with localizations and classifications. The nodes or localizations may represent verbal, perceptual, propositional or other entities of memory. These metaphors affect both the scientific investigation of memory and how we talk about and understand memory in everyday life.

One can talk about “storing” memories, “searching” them and “accessing” them. Memories and thoughts can be “organized”, memories that have been “lost” can be “looked for” and, if we are lucky, they can be “found”. More broadly, ideas in our minds are described as objects in a space, and the mind is a place that keeps “things”. We can “keep” ideas “in mind”, or ideas might be in the “front” or at the “back” or on “top” of our mind, or in the dark corners or “dim recesses” of the mind. They can be difficult to “grasp” or encounter difficulties “penetrating” into our mind. We even speak of people as of being “broad”, “deep” or “open” minded whereas others are “narrow, “shallow” or “closed”. Metaphors like these imply that humans think and talk of memory processes in terms of concrete, physical analogues. The Norwegian word for memory, “hukommelse”, derives from the word “hug”, which has as its etymological origin a name for a small bag in which to keep important things when travelling.

The physical store metaphor implies that anything that has entered the store will remain there until it is removed. One might fail to retrieve a piece of information from memory but it is nevertheless available there; an idea reflected, for example, in Tulving and Pearlstone’s (1966) distinction between availability and accessibility. The metaphor has inspired speculative theories that memories might disturb us and create psychological problems, without conscious awareness, and it implies that the important areas to look at for explanations of poor memory performance are linked to encoding and retrieval, rather than to the memory store...