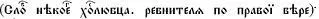

1 Christian idol-worshippers and ‘pagan survivals’

Dvoeverie. The technical term for the intermingling of pagan traditions with a superficial Christianity. In its extreme form, dvoeverie, (literally, ‘double faith’) is what a medieval Russian document (the ‘Sermon of a Lover of Christ’) defines as ‘when people who are baptised in Christ believe at the same time in Perun, Volos and other pagan gods’. More often, however, it is an unwitting practice of primitive folk customs while fulfilling the obligatory rites of the Orthodox Church. . . . [‘The Questions of the Priest Kirik to Archbishop Nifont of Novgorod’ (twelfth century), the decrees of the Stoglav Council of 1551 and the works of St Tikhon, Bishop of Zadonsk (eighteenth century)] as well as the occasional preserved sermon, give us considerable insight into the non-Christian folk religion of Russia in various periods . . . For all the strength of the Church’s denunciations some of these ‘double faith’ practices still persist today in the Russian countryside.1

The Modern Encyclopedia of Russian and Soviet History, 1979

The above citation offers a classic definition of dvoeverie, and is a good example of the sort of scholarship that has promoted the myth of double-belief in academia. Scholars from the nineteenth century onwards have used the term to describe the preservation of pagan elements by Orthodox Christian communities, generally citing or referring to the same medieval and early modern texts, leading to a widespread perception that Russian clerics invented the term dvoeverie to describe ‘in their own words’ the addiction of their flocks to ‘pagan practices’.2

This chapter will explore the key texts offered as evidence of double-belief from the Sermon of the Christlover, which pre-dates the Mongol invasions of the thirteenth century, to the eighteenth-century sermon of Bishop Tikhon Zadonskii on the festival of Iarilo. The Christlover, the most frequently cited sermon in the historiography of double-belief, contains the word dvoeverie within the characteristic framework of idol-worship by Christians, and the first section of this chapter is an attempt to unravel the meaning of the word as used in this context. Secondly, this chapter will compare the language of the Christlover with other sermons and texts in which the Church wrestles with popular unorthodoxy, asking whether this medieval and early modern textual evidence legitimizes modern historiographical usage of the term, and exploring medieval clerical terminology and concepts of unorthodoxy. Finally, it addresses the issue of whether these texts offer real evidence of the witting or unwitting preservation of ‘primitive folk customs’ by medieval Russian Christians.

The Sermon of the Christlover

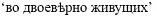

The earliest redaction of the Sermon of a Christlover and Zealot for the Right Faith 3 was discovered in 1847,4 together with a number of other texts discussed below, in a late fourteenth-century manuscript collection known as the Paisievskii sbornik.5 The Christlover sermon was first published in 1861, attracting a great deal of attention, and given that academic use of the term dates from the second half of the nineteenth century, this find doubtless launched the concept of double-belief in modern scholarship.6The Christlover sermon was fairly widely disseminated in the medieval and early modern period in both monastic literature and private reading compilations for the educated laity, and is cited in many other sermons on paganism. The date of this sermon’s composition is by no means certain,7 and authorship is also disputed. Some scholars attribute this sermon to Feodosii Pecherskii, the eleventh-century abbot of the Kievan Caves Monastery,8 and see it as written for the monastic community; others have strongly argued that it was intended for the edification of parish priests.9 What can be said with some degree of certainty is that this is an original Rus composition, rather than a translation from Greek, which dates from the pre-Mongol period.

The key phrase in this sermon, (usually translated as ‘double-believingly living’ or ‘living in double-belief’),10 has served as primary evidence that Christian communities preserved pagan beliefs and rituals in medieval Rus, and that this phenomenon was named double-belief by the medieval churchmen who expended great effort and many words in trying to combat it: Dvoeverie as a concept has a long history. It was already mentioned in one of the earliest monuments of Russian written culture: ‘Slovo nekoego khristoliubtsia’ [the Sermon of the Christlover]. The struggle of the Christian church for dominance in Russian villages is documented in chronicles, in the Stoglav, in numerous decrees and orders of Russian tsars, and so on.11

Even a scholar who does not advocate use of the term dvoeverie in the study of popular culture cites the Christlover as evidence of the medieval origin of the concept, and implies its existence in other pre-modern texts. As will be discussed in Chapter 3, this approach has been reflected in the work of a great many academics.

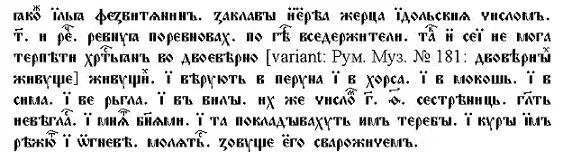

The key passage appears at the very beginning of the sermon, and reads as follows:

As Il’ia Fezvitianin, having slaughtered the priests, the idolatrous sacri-ficers 300 in number, and said ‘zealously I showed zeal for the Lord God Almighty’, thus also he [God?] cannot endure Christians living in double-belief [double-believingly living]. And they believe in Perun and in Khors, and in Mokosh, and in Sim, and in R’gl, and in the vily, of whom number 3.913 [variant 30] sisters. The uneducated say [this], and consider [them] goddesses, and therefore offer them sacrifices and cut cockerels for them and pray to the fire, calling it Svarozhich [son of Svarog?].

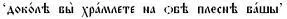

This passage immediately introduces a number of the complexities faced by the researcher who would seek to find in this and other early sermons evidence of Slavic pagan survivals – principally the problem of identifying potential textual sources of the paganism described. The ‘Il’ia’ referred to is the Old Testament prophet Elijah the Tishbite,14 who slew the prophets of Baal because he was ‘jealous for the Lord God of Hosts’.15 The Biblical Elijah asks the children of Israel: ,16 literally ‘how long do you limp on both your feet?’ This is usually translated as ‘how long halt ye between two opinions?’ and refers to their turning away from God to follow the prophets of Baal and ‘the prophets of the groves’ who ‘eat at Jezebel’s table’. The unknown Christlover, or possibly a later editor, has chosen the prophet Elijah and his idol-worshipping enemies apparently as a metaphor for Kievan Christians wavering between the Christian God and their earlier idols. The concept of ‘wavering between two opinions’ implicit in the choice of this Biblical passage suggests that here is used in the sense that it is used in many of the works discussed in the following chapter, meaning ‘in doubt’, ‘hesitatingly’, ‘uncertainly’. The Israelites more than once doubted God’s power, abandoned him for idols, and then returned again when convinced by a miracle.17It has been suggested that early Russian literature is ‘dominated’ by the Biblical model of a two-fold message – a historical message and a spiritual message:

To make sure the reader would not concentrate on the historical message alone and miss the spiritual sense of the written message – which, unfortunately, seems to be the case with most of our current interpretations of Orthodox Slavic texts – particular compositional devices were employed . . . A thematic clue consisted of scriptural references occurring in a compositionally marked place, namely, at the beginning of the exposition or direct narrative.18

Our ‘thematic clue’ to the spiritual message is clear – the wavering Israelites who cannot choose between God and the idol of Baal. The list of pagan deities that replaces Baal is thought by many scholars to be a later insertion into the text, probably based on the Primary Chronicle entry – or perhaps a common source – which tells us that in the year 980,

Vladimir then began to reign alone in Kiev, and he set up idols on the hills outside the castle with the hall: one of Perun made of wood with a head of silver and a mustache of gold, and others of Khors, Dazh’bog, Stribog, Simar’gl, and Mokosh.19

In the Christlover, ‘Simar’gl’ has been corrupted into ‘Sim’ and ‘R’gl’,20 and the mysterious vily have appeared, of whom more will be learned later in this chapter. Under the year 1114, the Primary Chronicle cites an unnamed chronicle on ‘the god Svarog’ of the Egyptians, and his son Dazh’bog, the Sun.21 This is probably the Byzantine Chronicle of John Malalas, the Slavonic translation of which contains glosses naming the deities Hephaestus and Helios as Svarog and Dazh’bog respectively.22

Various scholars have identified Old and New Testament references in the Christlover,23 (the latter generally indicated in the text by the phrase ‘Paul said’), in particular those from I Corinthians, in which Paul addresses the young Christian communi...