![]()

1

Asking agrarian questions: defining the family farm

The total disappearance of the family farm has been confidently predicted for almost a century and a half, and is still predicted today. While a great number have not survived into the twenty-first century, the fact that so many have done so, and in so many different lands, is remarkable. In what is now termed ‘late capitalism’ the continued existence of these non-corporate units of production seems anomalous, even archaic, to many observers. An integrated explanation is offered at the end of the book, but in this first chapter we show why they were expected to become extinct in a much earlier phase of capitalist evolution. Then we define what we mean by ‘family farm’. Some other issues of importance are introduced, to be more fully developed in later chapters.

Capitalism and farms: the classic ‘agrarian question’

The model

In Britain, between the fifteenth and eighteenth centuries, the characteristic farmer became no longer a peasant working strips of land received in return for services or quit-rent to a lordly holder, but a tenant, paying rent on leasehold land and working it himself or with the aid of hired labourers. Meantime, land had become the property of a growing class of persons who included descendants of feudal lords, but were also operators of a range of businesses. Labour was no longer tied to the provision of services to the lords but now dependent on wages and became ‘free’ to move into other fields of activity. This process took a long time, but it advanced faster and further in Britain than in other countries. The dissolution of the old feudal bonds, and the creation of a ‘free’ population of workers, also created a population of capitalists who accumulated that part of the product of labour not necessary to be paid to the workers for their survival needs, called the ‘surplus value’ of labour. They were themselves free to invest the accumulated surplus in new industries, and to compete with one another in the market. Adam Smith (1776:155) had already noted that the ‘surplus produce of the country … over and above the maintenance of the cultivators … constitutes the subsistence of the town’. This necessary relationship, reinterpreted by Marx (1867), provided the basis for explaining and (imperfectly) predicting the future of the world-wide capitalist economy.

From Marx, via Lenin and Kautsky, to the scale of farms

To Marx, who was simultaneously economist, sociologist and historian, the initial basis of capitalism was ‘primitive accumulation’ of capital. Following the English model, as he not altogether accurately interpreted it in the famous Chapter 24 of Capital I (Marx 1867), this was done through enclosures, in the context of a growing market economy, involving the separation of the worker from control of the means of production, whether as owner or renter. This, in turn, required production of commodities traded on the market, using paid labour. On the land, therefore, capitalists acquired the means of production, and labour became proletarian.1 The competitive discipline of ‘market dependence’ led to the growth of productivity of both labour and land, by means of improvements and innovations. This same growth in productivity lowered the costs of providing food and other raw materials for the growing urban and other non-agricultural population created by capitalist transformation. The ‘agrarian question’ of the nineteenth century concerned how surpluses earned from agriculture are transferred to investment in other economic sectors, specifically industry (Kautsky 1899; Lenin 1899). Capital acquired from farmers by merchants and usurers was one major channel. Another was ‘unequal exchange’, being the difference (in labour value) between returns for agricultural and industrial goods. A similar basic question came to dominate much non-Marxist economic thinking about developing countries in the twentieth century. The most common solution was to enlarge primary produce exports, taxed to provide the foreign exchange needed to fund industrial development.

While accumulation provided the resources needed for industry, and the labour ‘freed’ from the land also provided the labour for industry, there were important consequences among the agricultural population. These consequences happened whether formerly feudal lords converted themselves into capitalist large farmers, or whether such farmers arose by differentiation among the rural landowners. All aspects of the capitalist economy are competitive.2 Following the internal differentiation approach, and elaborating greatly on Marx, Lenin (1899) argued that competitive success would raise the wealthier peasants to the status of capitalist farmers while the less successful would fall to the level of proletarian labour. In the process, the ‘middle peasant’ would disappear over time. He illustrated these arguments from a large body of original data on Russian farming. The principal data were from inquiries carried out for local and provincial councils (zemstvo) set up in 1864 after the emancipation of the serfs in 1861. Lenin made principal use of data from ten of these inquiries. His research in the zemstvo data demonstrated that substantial differentiation had arisen among Russian peasant farmers, in land held and worked, livestock owned and farm machinery employed. He found what seemed clear evidence of ‘capitalist contradictions’ within the Russian village economy.

Kautsky (1899) cast his net more widely over Europe and found that the liberal economic revolution of the nineteenth century had not widely led to the breakdown in peasant societies that Marx had anticipated. Following Marx in treating the emergence of capitalism as primarily in manufacturing, he viewed the emergence of capitalist/proletarian division in the countryside in the context of already-established rural–urban trade. Market competition would favour the larger-scale producer who was better placed to adopt the many technical innovations employing wage labour. The smaller peasant would be squeezed out by this competition. But this would take time because farms grow larger and smaller for a variety of independent reasons. Kautsky, and many others who have used the same argument, saw the great advantage of the large farmer as lying in the economies of scale in production, in agriculture just as in industry where Marx and other earlier writers had seen them already. A capitalist farmer could afford to mechanize, deploy labour most efficiently, attract and apply credit, and make better use of scientific advances than a small farmer. Given these advantages, the large farmer could produce more efficiently. These competitive advantages, widely perceived to this day, also underlie the strong preference for capitalist farming exhibited in the modern era of neo-liberal free-market economics. But there have been long and profound debates on the question of the comparative efficiency of large and small farms. Yields per hectare are often higher on small farms than on larger farms. While a lot of the modern argument rests on a now outdated comparative study by Berry and Cline (1979), the yield advantage of smaller farmers has more recently been argued again, principally from modern data in Brazil, by Griffin et al. (2004). As Byres (2004) argues in response, it is necessary to distinguish between yield per hectare and yield per unit of labour, and on the basis of the latter the capitalist farm would seem to have clear advantage. Writing of a modern form of agrarian question, that we come to only toward the end of the book, Bernstein (2006) is at pains to point out that scale by itself no longer seems a major consideration in – at least scholarly – debate.

Friedmann, Chayanov and the viability of the commercial family farm

In a series of papers arising out of her doctoral research on the social history of modern wheat farming, Harriet Friedmann (1978a, 1978b, 1980) called attention to an aspect of events in the late nineteenth century and subsequently that had been surprisingly neglected. Kautsky (1899) had noted that the non-capitalist ‘middle peasant’ in Europe had shown considerable resilience in the last quarter of the nineteenth century, but regarded this as only temporary. It was not. After American wheat started to flow substantially into the European market in the 1870s, and prices declined worldwide, capitalist farms in both Europe and America gave way to family-operated farms, not the other way around. By 1935, after the second major period of low prices, the vast majority of commercial wheat production throughout the world was organized through household rather than wage labour. Yet by the 1870s capitalism had reached all wheat producing regions involved in trade, and in most of them there were already capitalist farms dependent on wage labour for production. Household and wage labour farms were therefore in direct competition, and in all this long period, it was the latter that yielded ground.

Friedmann’s complex explanation is in part technical.3 In the great plains of the USA, harvesting and, later, threshing machinery were rapidly being introduced, reducing the labour requirement on farms. As family farms grew in area by purchase and rental, so machinery suitable for the new average area (about 140 ha after 1920) also became available, making mechanized farming feasible for a family labour force averaging 1.5 male persons; data on female workers were, and usually remain, insufficient. While new land remained available, and with it credit, labourers were drawn off the large capitalist farms of the 1870s and 1880s to set up family farms. The large farms, requiring both to pay rising wages and to earn profits, were unable to compete with household farms that experienced neither of these constraints.

Capitalist farmers in Europe had to compete with American, Canadian and later also Australian and Argentinian producers using household labour at received wheat prices, which converged rapidly between countries and all moved together after the mid-1890s. German capitalist farmers, who for the most part had been feudal landlords in earlier days, sought to survive by coercive labour management and importation of Polish labourers; like French farmers, they were assisted by tariff protection. British farmers, who were not assisted in this way, mostly shifted out of arable production into livestock specialization, reducing their need for labour. In the British case, unlike the German, most farmers were already tenants and the decline in land values was borne by the non-farming owners of the land.

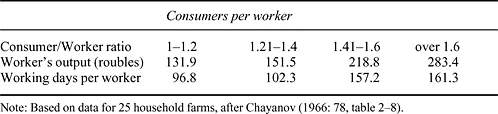

The technical conditions were important, but needed to be considered in conjunction with the contrasted social conditions of production in capitalist and household labour farms. Here Friedmann drew on the work of Aleksandr Chayanov (1923, 1925, 1966), who had used the same zemstvo data as Lenin, but relied also on inquiries by himself and his colleagues and students. Chayanov found the demographic stage of a household, as it first grew and then declined after the young became independent, to be dominant in bringing about differentiation between family farms, whatever their degree of commercial orientation.4 He concluded that the balance between consumers and workers within the household was the main determinant of the scale of production. In Table 1.1 we adapt his oft-quoted (and oft-misunderstood) table summarizing results in the district of Volokolamsk, west of Moscow.

Chayanov’s explanation relied on the fact that household workers consume the product of their work, whether as food and clothing or as money, but are paid no direct wages. Chayanov isolated the family farming household from its surrounding

Table 1.1 Productivity and intensity of work in relation to household composition at Volokolamsk, 1910

partly capitalist economy for theoretical purposes. He treated it as ‘a family that does not hire outside labour, has a certain area of land available to it, has its own means of production [i.e. tools, etc.], and is sometimes obliged to expend some of its labour force on non-agricultural crafts and trades’ (Chayanov 1966:51). There is no structural requirement for the farm to make a profit. The household is treated as a single, undifferentiated, producing and consuming unit. It will produce, or earn from work off the farm, what is needed to pay its rent (if any) and taxes, keep the farm functioning (in Marxist terms ‘reproduce’ it) and satisfy its own demands, but will not willingly do more than this. The consumer/worker balance of the family farm will change primarily through demographic process as families enlarge, grow old and are replaced. In effect, Chayanov was relying on the marginal analysis of neo-classical economics, so that an equilibrium level will be found where the marginal utility of outputs equals the marginal disutility of work (Hunt 1979).5

Collantes (2006a) usefully points out that, in comparing costs, returns and responses among farms operating under different production systems, Kautsky and Chayanov were in fact both using a neo-Darwinist evolutionary approach, formalized by Lawson (2003) as a population–variety–reproduction–selection model, in which market competition leads to selection of the ‘fittest varieties’. Kautsky worked with the commodity market, and saw the wage-paying capitalist farm as the fittest; Chayanov, also considering ability to compete in markets for the factors of production, saw the peasant farm as the fittest, and Friedmann essentially agreed with him. Commenting only on Chayanov, Ellis (1988a) drew attention to revisions introduced by the ‘new home economics’ which arose in the 1960s and 1970s, initially through recognizing that households not only farm or refrain from farm inputs to seek leisure, but they also produce their own utilities, the use values being obtained ultimately from their final consumption. In the presence of a labour market, inputs are determined not so much by preferences but by the going wage rate and price level, which yield opportunity costs of time spent on different activities. Contrary to Chayanov’s model, this allows decisions with respect t...