- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The field of evolutionary cognitive psychology has stimulated considerable interest and debate among cognitive psychologists and those working in related areas. In this collection, leading experts evaluate the status of this new field, providing a critical analysis of its most controversial hypotheses. These hypotheses have far reaching implications for cognition, including a modular view of the mind, which rejects, in its extreme form, any general learning or reasoning abilities. Some evolutionary psychologists have also proposed content-dependent accounts of conditional reasoning and probability judgements, which in turn have significant, and equally controversial, implications about the nature of human reasoning and decision making.

The contributions range from those that are highly critical of the hypotheses to those that support and develop them. The result is a uniquely balanced, cutting-edge evaluation of the field that will be of interest to psychologists, philosophers and those in related subjects who wish to find out what evolutionary considerations can, and cannot, tell us about the human mind.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Evolution and the Psychology of Thinking by David E. Over in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Cognitive Psychology & Cognition. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

The allocation system: Using signal

detection processes to regulate

representations in a multimodular mind

detection processes to regulate

representations in a multimodular mind

Gary L. Brase

IMPLICATIONS OF A MULTIMODULAR MIND

An aspect of evolutionary psychology that seems to distress a number of people is the degree of modularization it implies. The concept of a multi-modular mind can be difficult to accept. To be more precise, many sensible people readily accept that evolutionary theory is relevant to the study of the mind, and even that the evolutionary process is an important consideration in understanding how the mind was designed, but balk at the implication—drawn by most pre-eminent theorists in evolutionary psychology—that the mind is therefore composed of a large number of relatively specialized cognitive adaptations, or modules (Buss, 1995, 1999; Pinker, 1997; Tooby & Cosmides, 1992).

The reason for positing a large number of specialized mental abilities lies at the very foundations of evolutionary thinking. The evolutionary process must be enabled by a selection pressure—some aspect of the environment that poses a survival or reproductive problem for the species in question. Evolution happens by positive and negative feedback in relation to how well individuals (actually, genes that produce phenotypic traits that exist as part of individuals) solve that problem (assuming there is some variation in problem solutions). Since we are talking about specific problems, the better solutions will be specific and tailored to that problem domain (see Cosmides & Tooby, 1987, 1994); one cannot have a single solution for problems as diverse as finding food, courting mates, learning a language, and bipedal locomotion. Although there are debates about the nature of the processes and devices (Karmiloff-Smith, 1992; Sterelny, 1995), the mind must contain some form of specializations specific to these problem domains. Thus, it is proposed that there is a “learned taste-aversion” module, a “cheater detection” module, a “jealousy” module, a “theory of minds” module, “bluffing detection” and “double-cross detection” modules, and so on. (Tooby & Cosmides, 1992; also see Francis Steen's compendium for a tentative attempt at documenting the major categories of modules: http://cogweb.ucla.edu/EP/Adaptations.html.)

Although this process of module discovery appears to be ongoing, there already are concerns that evolutionary psychologists are creating a Frankensteinian mind. Some (Murphy & Stich, 2000; Samuels, 1998; Sperber, 1994) have referred to this evolutionary view of the mind as the “Massive Modularity” Hypothesis (italics added), an expression that seems to capture this concern quite well. Other, less restrained writers, have taken to calling evolutionary psychology “the new phrenology”. Some of this discomfort is likely to be the result of the sheer magnitude of the transition from traditional psychological models to evolutionary approaches. Behaviourist models of the entire mind contain a small handful of extremely general associative modules. Early computational models of the mental abilities tend to have a similarly small number of modules (e.g. the Atkinson & Shiffrin (1968, 1971) model of memory, which, prior to later modifications, had three basic modules: sensory memory, short-term memory, and long-term memory). Even the model proposed by Fodor (1983), which in many ways introduced the idea of modularity, restricted itself to highly encapsulated modules at the interfaces between the external world and the (still general-purpose) central functions of the mind. In the context of these historical roots, the evolutionary vision of the mind is truly a radical step.

Another indication of the profound nature of this viewpoint shift is that some early critics of evolutionary approaches seemed to miss entirely the implications of multimodularity and criticized domain-specific abilities for not being able to explain phenomena outside that domain. Cosmides' theory on reasoning about social contracts was considered to be falsified if it failed to account for improved reasoning of any kind, with any other type of content:

… contrary to the prediction of social exchange theory, facilitation in the selection task can be readily obtained with unfamiliar regulations that do not involve social exchange, any type of “rationed benefit”, or even any social situation at all.(Cheng & Holyoak, 1989, p. 299)

We ourselves have found, however, that the facilitation effect [in selection tasks] is not only produced by conditionals relating benefits and costs as Cosmides describes.(Manktelow & Over, 1990, p. 156)

Intriguing as this theory is, it is incorrect as it stands, since, as several authors have pointed out …, many of the best established facilitatory contexts do not involve costs and benefits that are socially exchanged.(Garnham & Oakhill, 1994, pp. 140–141)

Actually, the existence of a cognitive adaptation for dealing with social exchanges in no way precludes the existence of other cognitive adaptations for reasoning about other types of contents. In fact, it actually implies that there must be other reasoning procedures, given any similar selection pressures over human evolutionary history that involved making inferences about any other aspects of the world.

As some people grasp the “massiveness” of the multimodular mind model, they have tried to dismiss the basic idea using an argument of incredulity (see Samuels, 1998); claiming that the implications of multimodularity are simply too outrageous to be true. Although this “too massive” objection is a weak rhetorical argument (Dawkins, 1987), it does help to reveal some points that do, deservedly, require serious attention. One of the most important of these points is that the existence of a large number of modules necessitates some form of coordinating superstructure; a regulation of the modules that determines which modules are invoked at which times. In short, a multimodular mind requires some procedural government of modules.

The government of a multimodular mind can be usefully viewed as being a process just as much about the external world as it is about modules. The primary task of this process is to categorize situations that arise in the environment into the various domains in which particular inference procedures (modules) are invoked. As pointed out by Samuels, Stich, and Tremoulet (1999), “perhaps the most natural hypothesis is that there is a mechanism in the mind (or maybe more than one) whose job it is to determine which of the many reasoning modules and heuristics that are available in a Massive Modular mind get called on to deal with a given problem.” Samuels et al. call this device the “allocation mechanism”. I shall adopt this label, but with a modification: this allocation process is almost certainly a multifaceted system and, as such, it is probably misleading to refer to it as a mechanism (e.g. just as one does not usually refer to a “visual mechanism” but rather the visual system). I will, therefore, refer to the allocation system.

This chapter will also use certain other conventions in terminology. Cosmides and Tooby (1997, 2002) have used the term “multimodular” (as opposed to massively modular) to describe the general structure of the mind from an evolutionary viewpoint. Also, this chapter is concerned with the information entering and being processed within this mental allocation system, and I will refer to the output of the allocation process as different representations of information. That is, what the allocation system does is impute specific representational forms onto environmental situations (based on incoming information), so that each situation can be processed within a module suitable for such situations. (Admittedly, this description glosses over some complex processes, e.g. how representation, categorization, and the movement of these neurally instantiated representations to their appropriate modules, but it will have to suffice at this point.)

How does this allocation system work? In terms of a computational analysis (Marr, 1982), what is the computational problem that this system must solve? The situation that exists is a more-or-less continuous series of categorization tasks, all under situations of incomplete information, based on the properties of situations (cues) that are used as information (signals) for categorization. One of the most straightforward and widely used conceptualizations for such perceptual cue/category relationships (in situations with incomplete information) is Signal Detection Theory (SDT). SDT has been applied across many situations in which a categorization decision must be made based on cues with less than perfect cue validity and other situations of incomplete information.

PRIMER ON SIGNAL DETECTION THEORY

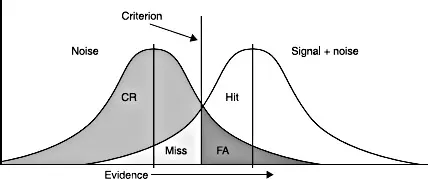

Signal detection (SD) involves the perception of some information from the environment (the signal) and a decision process for categorizing that information as either being or not being the target signal (detection; Green & Swets, 1966). The issue in signal detection is not just whether the signal actually exists (it may or may not), but also whether observers detect it (they may or may not). Therefore, there are four possible states of affairs:

1. “Hit” (correct acceptance) = the signal is present, and it is detected.

2. “False alarm” (incorrect acceptance) = the signal is absent, but it is detected.

3. “Miss” (incorrect rejection) = the signal is present, but it is not detected.

4. “Correct rejection” = the signal is absent, and it is not detected.

So long as the information is incomplete in some way, due to limits in the sensitivity to the signal, environmental and/or neural noise, or infidelity of the signal itself, all four of these outcomes will be possible. In real-world settings there is nearly always some amount of insensitivity, noise, or corruption in the signal, meaning there is always a distribution of ways the signal (or absence of a signal) may appear to an observer. An observer must therefore set a criterion (also called a cutting score, or C) for making decisions about whether the signal has occurred or not. As can be seen in Fig. 1.1, any given criterion results in errors (misses and false alarms); the task of the criterion generally is to minimize the effects of these errors, and a natural place to put

Figure 1.1 Generalized model of a signal detection situation. A judgement that there is only noise when there is, in fact, only noise (left-hand distribution) is a “Correct Rejection” (CR), whereas a judgement that there is a signal when there is actually a signal (right-hand distribution) is a “Hit”. Errors can occur when either no signal is judged to exist even though a signal does exist (a “Miss”) or a signal is judged to exist although there actually is no signal (a “False Alarm”; FA).

the criterion is at the point that minimizes both the miss rates and the false alarm rates. A criterion can be adaptively adjusted from this point, however, changing what is called the criterion bias, based on the relative costs of “miss” errors and “false alarm” errors. Placing the criterion in different locations changes the likelihood of these two errors, which are linked to one another in an inverse relationship (e.g. as in Neyman-Pearsonian statistical hypothesis testing theory, in which Type I and Type II errors are parallels to misses and false alarms).

It is important to note here that in most applications of Signal Detection Theory (SDT) the categorization itself is the crucial event that leads very directly to a decision and the end of the process. One reason for the focus on signal detection decisions as the end-points of the process is that most signal detection tasks are for fairly specific tasks. The topics most strongly associated with Signal Detection Theory are narrowly defined areas of decision making; from the original conception of Signal Detection Theory (identifying sonar objects as being either ships or nonships), to specific aspects of memory and attention (e.g. Posner, Snyder, & Davidson, 1980), to specific aspects of language (e.g. Katsuki, Speaks, Penner, & Bilger, 1984), taste and smell (e.g. Doty, 1992; Jamieson, 1981), and to jury decision making (Mowen & Linder, 1986). In each of these areas, the decision frame has already been constructed around a rather specific issue (also see Pastore & Scheirer, 1974, for a general discussion of Signal Detection Theory applications).

Even in understanding the behaviours of other animals, in which signal detection has also been useful, the animal signals have typically been signals of specific things (e.g. alarm calls, mate attraction, warning coloration, etc.; e.g. Cheney & Seyfarth, 1990; Marler, 1996). Similarly, the detection of a signal has usually been directly linked to some specific behavioural response. Signal detection models in the animal world, however, more often involve the idea of detection errors that are caused not by random noise or insensitivity, but by other agents (i.e. other animals). Take, for example, the situation of a predator (say, a hawk) scanning the landscape for prey. A “hit” for the predator is a correct sighting of prey, and a “correct rejection” is a correct rejection of nonprey objects. The predator can be induced to commit miss errors, however, by prey that mimic the appearances of foul-tasting animals (Gould & Marler, 1987; one could also view th...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Current Issues in Thinking and Reasoning

- Full Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of contributors

- Introduction: The evolutionary psychology of thinking

- 1. The allocation system: Using signal detection processes to regulate representations in a multimodular mind

- 2. Is there a faculty of deontic reasoning? A critical re-evaluation of abstract deontic versions of the Wason selection task

- 3. Evolutionary psychology's grain problem and the cognitive neuroscience of reasoning

- 4. Specialized behaviour without specialized modules

- 5. From massive modularity to metarepresentation: The evolution of higher cognition

- 6. Probability judgement from the inside and out

- 7. Evolutionary versus instrumental goals: How evolutionary psychology misconceives human rationality

- Author index

- Subject index