- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Although Adam Smith, the father of modern economics, died over two hundred years ago his presence is still felt in many areas of contemporary economics. In this volume some of the world's leading economists pay tribute to Smith's continuing importance. The contributors, including ten Nobel Laureates, consider themes as diverse as Smith's use of data, his attitude to human capital and his views on economic policy. Heirs to Smith as leaders of the discipline, they also reflect upon the current state of economics, assessing the extent to which it measures up to the benchmark established by its founder.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Adam Smith's Legacy by Michael Fry in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

THE OVERDUE RECOVERY OF ADAM SMITH’S REPUTATION AS AN ECONOMIC THEORIST

Paul A.Samuelson

Adam Smith had a powerful influence on the history of ideas, ideas of the educated non-economist public and most particularly of governmental policy-makers and their voter constituencies. David Ricardo’s great influence was more narrowly focused on contemporaneous and subsequent economists. Macaulay’s general schoolboy knew The Wealth of Nations but not Ricardo’s Principles of Political Economy.

So to speak, Smith paid for his popularity with the lay public by being regarded among professional economists as ‘old hat’ and a bit prosaically eclectic. Ricardo, by contrast, wrote so badly as to provide that quantum of obscurity sufficient to evoke academic attention and overestimation. Karl Marx, it may be said, shared in the Ricardian tradition in more ways than is conventionally recognized.

As I reflect back upon what seems to have been a systematic undervaluation of Adam Smith in professional circles of six decades ago, I discern that a major responsibility for this lies with two scholars. It was David Ricardo himself who believed that Adam Smith’s basic system was flawed at its core. Indeed, it was this critical view of Smith that caused Ricardo to write his Principles. The economists’ world, blinded by Ricardo’s reputation for brilliance and unable to recognize in his murky exposition the many non sequiturs contained there, accepted Ricardo’s indictment at its face value.

The second authority influential in playing down Smith’s worth was my old master, Joseph Schumpeter. Long before the Harvard days of his greatest reputation, the young Schumpeter’s brilliant German work, Economic Doctrine and Method (1914), had patronized Smith with faint praise. Never did Schumpeter really alter this evaluation, as his posthumous classic of 1954 makes clear. Schumpeter seems to put ahead of Smith as a theorist such predecessors as Cantillon, Hume and Turgot; and subsequent to him, Schumpeter would surely have regarded as Smith’s superiors such diverse scholars as A.A.Cournot, Léon Walras, and (I vaguely remember from Schumpeter’s 1935 Harvard lectures) Alfred Marshall. Whereas Ricardo regarded Smith as having defected from a proper labour theory of value, in Schumpeter’s eyes Smith’s crime was that of mediocrity, lack of originality, and excessive imitativeness. (When my colleague Robert L.Bishop prepared a definitive debunking of Ricardo’s critique of Smith, he informed me that Schumpeter paradoxically proved to be one of the few scholars who correctly recognized Ricardo’s lack of cogency and who defended Smith for his full due.)

Most economists of the generations between 1930 and 1990 have had limited interest in and knowledge of the history of economic analysis. They gladly go for whole hours without thinking about the subject.1 Therefore, Schumpeter’s evaluation was influential to them and set the climate of opinion.

Perhaps I ought to add a third name to the list of those who served to play down the merits of Smith relative to Ricardo: Karl Marx. Marx cannot be judged by tvventieth-century economists to have been competent enough in economic theory to serve as a useful judge of Smith’s analytical merits. But the fact that both neoclassical economics and Marxian economics trace back directly to Ricardo has undoubtedly raised his relative reputation. (As I once put it, the poet Robert Frost gained doubly when attracting both low-brow and high-brow readers).

If Marx is a third name, the temptation becomes strong to add Piero Sraffa as a fourth and recent name. I am not referring to the Sraffa who was a superb editor, but rather to the Sraffa who leads a school against ‘marginalism’ and ‘mainstream economics’ generally. Luigi Pasinetti, Pierangelo Garegnani, Nicholas Kaldor, and Joan Robinson, when they seek in classical economics a Kuhnian alternative paradigm to modern mainstream economics, are least attracted to Smith’s and Mill’s kind of supply-and-demand analysis and most attracted to Ricardian constructions.

In this brief exposition, I propose to audit a few of the most important criticisms of Smith, made by Ricardo and other authorities. My verdicts turn out mostly to be in Smith’s favour; but more important is the analytic demonstration of why various indictments are invalid.

INDETERMINACY FROM TOO MANY ‘RESIDUALS’?

My own failure as a student to accord to Smith the admiration he deserves as a theorist can be traced neither to Ricardo’s criticisms nor to Schumpeter’s faint praise. There was an oral tradition at the University of Chicago, hard for me to pin down more than half a century later, that Adam Smith had a correct but rather empty supply-and-demand theory of price, based on a cost-of-production equality that involved indeterminate factor-price variables.

Bluntly put, Smith was alleged to have too many ‘residuals’. Labour got its subsistence wages; land rent got its residual rent; and interest or profit was also a residual return. When A=B+C+D, and only B is determinate in the equation, then to write successively C=A-B-D and D=A-B-C was still to be left with too many endogenous unknowns.2

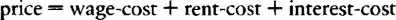

Samuelson (1977), on the 200th anniversary of The Wealth of Nations, provided both a literary and mathematical vindication of Smith’s system based on his tri-partite breakdown

No redundant residuals are left; and no inconsistencies are involved.

Population grows (algebraically) when the wage rises (algebraically) above the market cost of a specified basket of subsistence goods. Capital accumulates (algebraically) when interest or profit rate exceeds (algebraically) some specifiable minimum required yield. Land is fixed in supply: for simplicity it is needed only to produce corn. Other goods (manufactures) need only labour and corn as inputs. All production is time-phased. Landowners and capital-goods owners spend their rent and profit incomes according to their tastes, along with utilizing income for (algebraic) capital accumulation.

Smith is right to perceive that there is only one (real wage, profit rate, real rent/acre) that clears all supply-demand markets in the long run. He is right to perceive that land rent is a surplus that can be taxed without affecting real price ratios. He is right to perceive that the growth mode is the cheerful state for wages when capital accumulation precedes and drives up population. He correctly perceives that accumulation ultimately reduces the interest rate and raises the rent rate; also accumulation permits a higher subsistence wage if workers become more chary of reproducing. I say to Knight and to Samuel Hollander (1987:78): there is no redundancy, and there is no self-contradiction in this Smith. QED. And I add for Ricardo, even if land were redundantly infinite in supply, accumulation of capital relative to population would compete down the profit rate (of course at the same time competing up the real wage). So what is the problem?

HOW SMITH WITHSTANDS MARX’S DOUBTS

One line of criticism of Smith’s theoretical system traces peculiarly to Karl Marx. Few commentators seem to have noticed how repeatedly preoccupied Marx was by Smith’s purported breakdown of price (and of national income) into the triad of components: wages, land rents and interest or profit. Marx accused Smith of omitting the fourth component of used-up raw materials or depreciation of durable capital instruments. Friedrich Engels, as editor for Marx, had to grapple with repetitive fragments of manuscript dealing with this accusation and adding up to what must involve tens and tens of thousands of words.

Actually, Smith is in the clear. He even uses the magic words ‘value-added’, deeming the used-up raw materials in a loaf of bread as being decomposable into the triadic wage-rent-interest components of previous stages of production. In one sentence Marx does seem to glimpse the correctness of Smith’s taxonomy and accounting in a very special case. When labour and land alone produce wheat; and labour with wheat produces flour; and labour with flour produces finished bread —what today we would call the triangular Leontief input/output matrix of the simplest ‘Austrian’ case—then Marx conceives that Smith’s value-added might work as a special trick. But, when iron produces coal and coal produces iron, Marx senses that an infinite regress without a finite beginning is involved. He complains that Smith is sending us from pillar to post and back again. Even though Smith is essentially right, any modern investigation must provide the rigour not to be expected in an eighteenth-century writer.

Actually, Marx’s own Tableaux of Reproduction in Capital, Volume II, properly understood, provide the vindication of Smith against Marx’s charge of circularity. V.K.Dmitriev (1898) shows Marxians and non-Marxians how the simultaneous equations of the input/output tableaux do vindicate Smith. I give Marx top marks for sensing that rigour is needed for auditing Smith’s heuristics. (See Dorfman, Samuelson and Solow (1958) for discussion of the convergent infinite matrix-multiplier series, the so-called Cornfield-Leontief Gaitskell multiplier chains, that are shown to augment compatibly the Dmitriev-Marx simultaneous equations resolution of Smith’s value-added accounting.)

The Marx of the labour theory of value came close to committing hara-kiri by pressing home the fallacy (sic) of Smith’s infinite and illegitimate regression. For, as the 1958 analytics show, when land is free and the interest rate is zero—the rude early society in which Smith, Marx, Ricardo and Walras agree that the labour theory of value would be exact as a theory of competitive price—deer, beaver, coal and iron could not have their prices each equal to respective embodied total labour contents, (‘live’, direct labour plus ‘dead’, indirect labour) if a convergent infinite geometric progression did not justify Smith’s labour value-added theory. Among writers sympathetic to Marx, Ian Steedman (1977) has noted this same point and properly faulted Marx for it.

SMITH AS MERELY A SUPPLY AND DEMAND MONGER

He who is Napoleonic is often paranoid. Having regarded Smith’s supply-and-demand relations between price and wage-plus-rent-plus-interest components as emptily eclectic, Marx thought Smith’s tautologies were not even genuine tautologies. It is ironical that Marxians and neoclassicists like Knight joined in the failure to perceive the genius of Smith’s formulation of a general equilibrium model.

In recent times Samuel Hollander has been lampooned rather than praised for seeing supply and demand mechanisms evetywhere in the classical writers. Even Mark Blaug (1978:66) writes of Hollander as making Smith into more of a Léon Walras than a Ricardo, which I deem not to be a reductio ad absurdum but rather a merited compliment for Smith. (Given their respective dates, we might better compliment Walras for his Smith-like approach to general equilibrium.) Followers of Piero Sraffa or Marx, who are not identical sets, agree in their desire to reject mainstream equilibrium theory. In the sense of Thomas Kuhn’s The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1962), they want to regard the classical (i.e., the pre-1870) system as an alternative paradigm, a different and better paradigm to the modern ones. That is why they reproach Hollander for claiming to discern supply and demand content in the classical writers and why they prefer a Ricardo to a Smith.

Even before the 1951 and 1960 eruption into print of Sraffa, my reading of every one of the classical masters found in them an earlier and more primitive version of the Walras-Marshall-Wicksell system. As I once put it, ‘Inside every classical writer there is a modern economist trying to get born.’ Thünen is a notorious case where even marginalism is present; but Ricardo’s numerical examples and concepts of external-margin and internal-margin land rent represent a significant advance beyond Smith’s and Hume’s excellent apperception that inelastically-supplied land earns a rent whose causation runs from rather than towards demand and competitive prices.

AVOIDING OVER-CONCRETE IMPLICIT INFERENCE

George Orwell would savour the Maoist dictum: What is not explicitly permitted is forbidden. Yet something like this doctrine can be espoused in setting up the rules of the game for commentators on any ancient writer such as Smith: if the writer does not explicitly say (in his language) ‘I am stipulating that cost-prices are constant, regardless of changes in composition of demand’, the commentator must abstain from writing that ‘presumably’ or implicit...

Table of contents

- COVER PAGE

- TITLE PAGE

- COPYRIGHT PAGE

- FIGURES

- TABLES

- FOREWORD

- 1 THE OVERDUE RECOVERY OF ADAM SMITH’S REPUTATION AS AN ECONOMIC THEORIST

- 2 SMITH’S USE OF DATA

- 3 THE GENERAL THEORY OF SURPLUSES AS A FORMALIZATION OF THE UNDERLYING THEORETICAL THOUGHT OF ADAM SMITH, HIS PREDECESSORS AND HIS CONTEMPORARIES

- 4 PUBLIC ECONOMIC POLICY: ADAM SMITH ON WHAT THE STATE AND OTHER PUBLIC INSTITUTIONS SHOULD AND SHOULD NOT DO

- 5 ON THE WEALTH OF NATIONS

- 6 THE SUPPLY OF LABOUR AND THE EXTENT OF THE MARKET

- 7 THE INVISIBLE HAND IN MODERN MACROECONOMICS

- 8 ADAM SMITH AND HUMAN CAPITAL

- 9 THE PRESENT STATE OF ECONOMIC SCIENCE

- 10 ECONOMICS: RECENT PERFORMANCE AND FUTURE TRENDS

- APPENDIX TO CHAPTER 3