- 336 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Peloponnesian War

About this book

The range and extent of the Peloponnesian War of the fifth century BC has led to it being described as a 'world war' in miniature. With the struggle between Athens and Sparta at its core, the twenty-seven-year conflict drew in states from all points of the compass; from Byzantion in the north, Crete in the south, Asia Minor in the east and Sicily in the west.

Since Thucydides described the war as 'the greatest disturbance to befall the Greeks' numerous studies have been made of individual episodes and topics. This authoritative work is the first single-volume study of the entire war to be published in over seventy-five years. Lazenby avoids the tendency of allowing historiography to obscure the analysis, and while paying due attention to detail, also looks at the fundamental questions of warfare raised by the conflict.

Within a narrative framework, Lazenby concentrates on the fighting itself, and examining the way in which both strategy and tactics developed as the conflict spread. Not afraid to challenge accepted views, he assesses the war as a military rather than a political endeavour, evaluating issues such as the advantages and limitations of sea power. A readable and clear survey, this text offers a balanced discussion of controversial themes, and will appeal to ancient historians, classicists and all those who are interested in military history.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

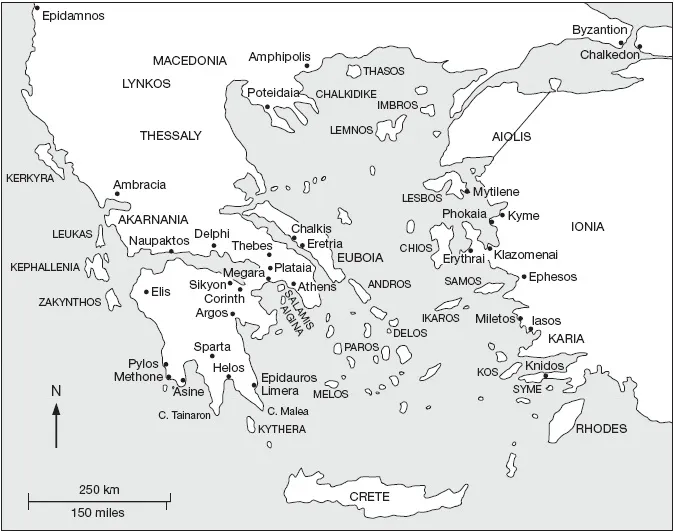

BACKGROUND

On a rainy, moonless night in the spring of 431, a force of a few more than 300 Thebans entered Plataia at about the time of ‘first sleep’ (2.2–3).1 Twenty-seven years later, almost to the day (5.26.1–3), a starving Athens, blockaded by land and sea, was forced to accept Sparta’s terms. During those years, war raged the length and breadth of the Greek world, from Byzantion in the north to Crete in the south, and from Asia Minor in the east to Sicily in the west. Since at least the first century this conflict has been known as the ‘Peloponnesian War’, and only a pedant would now seek to call it something different.2 It was also the subject of one of the greatest of all historical works, by the Athenian, Thucydides.3

Map 1 Greece and the Aegean

In his first sentence, Thucydides defines his subject as ‘the war of the Peloponnesians and Athenians’, and elsewhere (2.9) he lists the allies of the two sides. On the one were all the states of the Peloponnese except the Argives and the Achaians, though, of the latter, the people of Pellene supported the Spartans from the beginning, and the rest later (within three years, judging by 2.87.6); outside the Peloponnese, the Spartans also had the support of the Megarians, Boiotians (except the Plataians), Opountian Lokrians, Phokians and, from among the ancient Corinthian colonies in the west, the Ambrakiots, Leukadians and Anaktorians.

On the side of the Athenians, among mainland states, were ranged only the Plataians, the Messenians of Naupaktos, most of the Akarnanians, and, later, the Ozolian Lokrians (cf. 3.95.3). But their main strength lay in their far-flung empire in and around the Aegean, comprising the relatively independent islands of Chios and Lesbos, and the many other states Thucydides classes as ‘tribute-paying’ (hypoteleis: 2.9.4). In addition, they were supported by Zakynthos and Kerkyra (Corcyra, Corfu) in the west.

The core of the Spartan alliance was what is often called nowadays the ‘Peloponnesian League’, but which was known to contemporaries more simply and more suggestively as ‘the Lakedaimonians and their allies’.4 This probably had its origins in the mid-sixth century, and by the end of that century, Kleomenes, king of Sparta, is said to have gathered an army ‘from all the Peloponnese’ (Hdt. 5.74.1). The only Peloponnesians who consistently remained outside the Spartan alliance were the Argives, although most of the Achaians were apparently independent at the beginning of the war.

From Thucydides’ account of the debates in Sparta that led to war, and other things that he and other sources report, we can see that the Spartan alliance had no real existence except as an instrument whereby the Spartans could mobilize their allies. They held the initiative and could not be committed to a policy of which they disapproved. Moreover, if the alliance did go to war, its forces were led by Spartans and remained firmly under Spartan control. Thus, in our war, allies such as the Corinthians and Megarians took their complaints against the Athenians to Sparta in the first instance (1.67ff.), and it was only after the Spartans in assembly had voted that the Athenians had broken the treaty of 446 (1.87) that they summoned a meeting of their allies to secure their formal vote for war (1.119).

Conversely, however, Sparta’s allies could not be committed to a policy of which they disapproved. For example, although on this occasion the allies did approve, it appears from something Corinthian envoys at Athens are earlier said to have claimed (1.41.2, 43.1) that the Spartans wanted to go to war with the Athenians at the time of the revolt of Samos in 440, but that the Corinthians persuaded the allies not to back the proposal. Moreover, the Corinthians apart, Sparta’s allies now included the Boiotians, who had their own federal league, and who provided a powerful counterweight to Spartan dominance of the Greek mainland. Relations between the Boiotians and the Spartans were always somewhat strained, depending on whether the former saw the Athenians or the Spartans as the greater threat. But from 457 to 447 they had been under Athenian control, and this probably meant that at this time they felt they had more to fear from the Athenians.

The Spartans tried to ensure that allies who were more susceptible to pressure had ‘friendly’ (usually oligarchic) governments (1.19), and occasionally used force to secure this, as in the case of Sikyon in 418 (5.81.2). But they normally left their allies more or less alone (even, to an extent, in foreign affairs), provided that their own interests were not endangered. In the winter of 423/2, for example, at a time of truce with Athens, they apparently did not interfere in the war between their two most important allies in Arcadia, Mantineia and Tegea (4.134.1). Nor is there any evidence that they maintained garrisons in allied cities, as the Athenians sometimes did, and, unlike them, they exacted no tribute (1.19). If the stele recording contributions from Sparta’s allies (ML 67=Fornara 132) really does refer to the time of the Peloponnesian War, one has only to compare it with the so-called ‘Athenian Tribute Lists’ to see the difference. Apart from anything else, the Athenians did not see the need to list contributions of raisins from their allies, as the Spartans evidently did.5

Thucydides, indeed, has both King Archidamos of Sparta and Perikles single out the lack of financial reserves as a weakness of the Spartan side (1.80.4ff., 1.41.2ff.), a weakness which Sparta’s Corinthian allies allegedly proposed to remedy by borrowing from the treasuries of Delphi and Olympia (1.121.3). In one respect it was clearly true that the Spartans’ lack of financial reserves weakened their war effort. As we shall see, the Spartans could not defeat Athens until they were able to match her at sea, and if there was any borrowing from Delphi or Olympia, as a clause in the truce of 423/2 may suggest, it obviously did not amount to much.6 It was not until the destruction of the Athenian Sicilian expeditionary force gave the Spartans and their allies a hope of achieving naval supremacy that they galvanized themselves into trying to assemble an adequate fleet, and even then they came to rely heavily on Persian financial support.

Apart from the cost of building and maintaining warships, their crews had to be paid. Slaves were probably used more than has sometimes been said, but the majority of oarsmen were probably always free men, and the cost of paying even a single trireme’s crew could rise to a talent (6,000 drachmai) a month (6.8.1).7 Although oarsmen who served on their own national ships would presumably remain loyal, it appears from various passages in Thucydides that most states hired rowers from elsewhere. Thus the Corinthians claim that, by using their own resources and funds borrowed from Delphi and Olympia, they will be able to lure away the foreign sailors in the Athenian navy by higher rates of pay, and Perikles’ counter-claims (1.143.1–2) imply that the Corinthian one was at least partly true. He declares that the Athenians could match their enemies from their own citizens and the aliens resident in Athens, and that they had more and better helmsmen and other crew-members than all the rest of Greece. But he then goes on to argue that the foreigners serving Athens would not risk exile following defeat for the sake of a few days’ high pay.8 The most vivid evidence that rates of pay were important is the story Xenophon tells (Hell. 1.5.6) of how, when the Persian prince Cyrus asked Lysander how best he could please him, Lysander replied, ‘if you add an obol to the pay of each sailor’.

But, although the Spartans could not hope to defeat the Athenians unless and until they were able to win at sea, and although they could not achieve that with their existing financial resources, equally the Athenians could not defeat the Spartans unless and until they were able to win on land, and this was not a matter of finance, but of gaining allies. As Perikles also says (1.141.6), ‘in a single battle, the Peloponnesians and their allies are able to stand up to all the Greeks’. In this same passage, Thucydides has Perikles single out as a further weakness of the Spartan side the fact that it had no single council chamber (bouleutêrion: 1.141.6). Presumably he was thinking primarily of the fact that the Athenians could virtually ignore their allies when it came to strategic decisions, whereas the Spartans could not. But he implies that some consideration was given to a common strategy at the meeting of the Spartans’ allies which backed their decision to go to war, in 432, there was another meeting at Corinth in the winter of 413/12 (8.8.2), and one would guess that there were similar meetings most winters, when campaigning halted. In any case, whether the lack of a single decision-making body seriously weakened Spartan operations is another question. If anything, it is arguable that the Athenians’ more rigid control was the more dangerous because it sometimes led to revolt, as in the case of Mytilene in 428. It was only in the aftermath of the Peace of Nikias in 421 that the Spartans faced real trouble from their allies, and the Athenians faced far worse after the disaster in Sicily. Indeed, Thucydides has the Corinthians claim that their general obedience to orders was one of their side’s strengths (1.121.2).

Here Thucydides may particularly have had in mind the contrast between the oligarchic system of government which they and many of Sparta’s allies shared, as opposed to the democratic system of Athens. We know little about most of Sparta’s allies, but in Corinth, for example, the supreme deliberative body apparently numbered only 80 men, and within this group executive power seems to have been wielded by the eight probouloi – a term which Aristotle regarded as quintessentially oligarchic.9 Almost certainly there was a property qualification for belonging to the council, as was the case with the councils in Boiotian cities in the early fourth century (Hell. Ox. 16.2). States which had restricted access to political rights of this kind prided themselves on their eunomia (good order),10 and this was pre-eminently the virtue claimed for the Spartan system.

This was certainly oligarchic insofar as it restricted full political rights to a minority of the population. Women apart, there was, in effect, a property qualification for citizenship in that all Spartan citizens had to belong to a military mess (phidition, syssition), and in order to do so had to make monthly contributions in kind (cf. Aristotle, Pol. 1271a27ff.). Spartans could also lose their rights for other reasons, for example, cowardice (cf. 5.34.2). Second-class Spartans may have been known as ‘hypomeiones’ (inferiors: Xen., Hell. 3.3.6), and, if so, they were sufficiently numerous by Xenophon’s time to be listed with helots, neodamôdeis (new citizens) and perioikoi (neighbours). Of these, the neodamôdeis were probably helots who had been emancipated for military service. They first appear in the 420s (5.34.1), when they may have numbered 1,000 (cf. 5.49.1), and we later hear of their forming part of a force of 600 hoplites sent to Sicily in 413 (7.19.3), of 300 being sent to Attica in 412 (8.5.1), and of a few forming part of the garrison of Byzantion in 408 (Xen., Hell. 1.3.15). Despite the term used for them, they were almost certainly not full citizens. Perhaps, rather, as free men, and possibly settled at strategic points on the frontier – the first were settled at Lepreon (5.34.1) – they became, in effect, perioikoi.11 These last were the free population of the outlying towns and villages in Spartan territory. Although classed as Lakedaimonians like the Spartans themselves (cf., e.g., 4.53.2),12 and expected to fight alongside the Spartans at least in campaigns outside the Peloponnese,13 even sometimes to command in such operations (8.22.1), the perioikoi were certainly not full citizens in the sense that they could attend the assembly in Sparta or hold Spartan office.

The extent to which they had some kind of internal self-government in their own communities is debatable. Isokrates claims that their ‘cities’ (poleis) had less ‘power’ (dunamis) than Attic demes (Panath. 179), but this is equivocal: to class perioecic communities as ‘poleis’, as, for example, Herodotos also does (7.234.2), suggests that they had some autonomy, but if they had less power than Attic demes, it amounted to very little, and this is borne out by their lack of civic buildings before they won freedom from Sparta.14 Possibly the truth of the matter is that they were simply part of the Spartan state, and, as such, subject to the same authorities as the Spartans themselves. Isokrates, after all, also says that the ephors could put perioikoi to death without trial, and Xenophon says that the kings of Sparta possessed land in many of their communities (LP 15.3).

We do not know how many of them there were, but, according to Herodotos (9.11.3, 28.2), there were as many (5,000) as there were Spartans at the battle of Plataia in 479, and the legends of the distribution of land by the lawgiver, Lykourgos, suggest that there were over three times as many (Plut., Lyk. 8.3, cf. Agis 8). Probably even more numerous were the helots who worked the Spartans’ land and were normally simply regarded as slaves (cf., e.g., 5.23.4). Again, we do not know how many there were, but Herodotos’ statement that there were seven for every Spartan at Plataia (9.10.1, 28.2, 29.1), though probably untrue in itself,15 at least gives some idea of just how numerous they were believed to be.

All in all, then, the full citizens of Sparta were swamped in a sea of second-class citizens of various kinds: a passage in Xenophon (Hell. 3.3.5) suggests that in the early years of the fourth century they formed less than 2 per cent of the adult male population. But within this privileged group power was probably more widely distributed than in Corinth, for example. The titular heads of the Spartan state were the two kings, one from each of two, separate royal families. Their prestige and wealth – they were regarded as semi-divine, as descended from Zeus via the hero, Herakles – gave them enormous influence, and there are very few instances of the Spartans going against their wishes, though one famous example is precisely their rejection of King Archidamos’ advice not to go to war with the Athenians in 432 (1.80ff.). Their constitutional position is perhaps best summed up by the monthly ceremony in which they swore to rule according to the established laws of the state, and the ephors swore, on behalf of the state, to maintain their position, provided that they kept their oaths (Xen., LP 15.7). But, for our purposes, the main thing to remember is that one of the kings normally held supreme command in war. For example, one of them led the annual invasions of Attica during the war, and King Agis led the invasion of the Argolid in 418, and commanded at the battle of Mantineia.

The monthly oath indicates that the most important officials after the kings were the five ephors (ephoroi). These were elected annually from and by the citizens of Sparta, to hold office from autumn to autumn (cf. 5.36.1), and during their year of office held virtually supreme power (cf. Aristotle, Pol. 1270b8). This was symbolized by their not even having to stand in a king’s presence (Xen., LP 15.6), and by the fact that dates were expressed by citing the name of one of the ephors (cf., e.g., 2.2.1), not the regnal years of the kings. Ephors presided over the assembly (cf. 1.87.1), and carried out its decisions – for example, it was probably they who mobilized the army. They also had authority over all other officials (Xen., LP 8.4; Aristotle, Pol. 1271a6), even being empowered to arrest kings (1.131.2), though not to try them. They thus resemble Roman officials with imperium rather than the officials of other Greek states. There is no evidence, for example, that any ephor was ever charged with an offence during his year of office, let alone deposed, apart from those who, in wholly exceptional circumstances, opposed the reforms of Agis IV and Kleomenes III in the third century (Plut., Agis 12, Kleom. 8). Indeed, unlike Roman officials, ephors even appear to have enjoyed immunity from prosecution after their year of office.

Why the Spartans entrusted these seemingly unique powers to the ephors is problematical, but it may have been their way of reconciling the discipline on which they prided themselves with the equality among themselves they also claimed. By Xenophon’s time, at any rate, they were sometimes referred to as ‘equals’ (homoioi: e.g. Hell. 3.3.5). Thus ephors could almost certainly only hold the office once, so their long-term influence was negligible, unlike that of the kings, who, naturally, held office for life, and Aristotle also says that the ephors were very much ‘men of the people’ and often poor (Pol. 1270b8–10). In other words, their influence went solely with the office.

In particular, they appear to have had little or no military function. It is true that two of them are said to have accompanied a king on campaign (Xen., Hell. 2.4.36; LP 13.5), but even if this is true,16 they are said never to have interfered except at the king’s request. They may thus have had some ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- MAPS

- PREFACE

- ABBREVIATIONS

- NOTE ON THE SPELLING OF GREEK NAMES AND THE TRANSLITERATION OF GREEK

- 1: BACKGROUND

- 2: CAUSES

- 3: STALEMATE

- 4: INTERLUDE

- 5: ATHENS ASCENDANT

- 6: SPARTA RESURGENT

- 7: PHONEY PEACE

- 8: SICILIAN ADVENTURE

- 9: DISASTER IN SICILY

- 10: A DIFFERENT KIND OF WAR

- 11: WAR IN THE NORTH

- 12: REARGUARD ACTION

- 13: ENDGAME

- 14: CONCLUSIONS

- APPENDIX

- NOTES

- BIBLIOGRAPHY

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Peloponnesian War by Professor J F Lazenby,J.F Lazenby in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Greek Ancient History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.