1

THE LANDSCAPE AS A SOURCE OF

HISTORICAL EVIDENCE

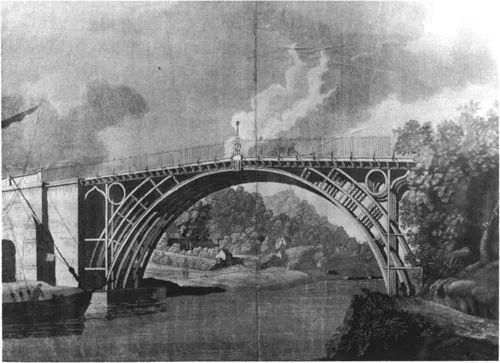

The Ironbridge Gorge is often called the ‘Cradle of the Industrial Revolution’. It enters history books as the place where Abraham Darby first smelted iron in 1709 using coke and not charcoal as a fuel, thus paving the way for the mass-production of iron. Other technical innovations followed, including the first use of iron rails, and new contributions to the technology of steam engines and locomotives. And it was here in 1779 that the newly discovered properties of iron were demonstrated with a spectacular iron bridge that spans the Severn Gorge, the first iron bridge in the world (fig. 1.1). The Iron Bridge has become a symbol of both the Industrial Revolution and Britain’s eighteenth-century industrial achievements.

1.1 ‘A View of the Cast-Iron Bridge’, E.Edgecomb 1786 (SSMT40)

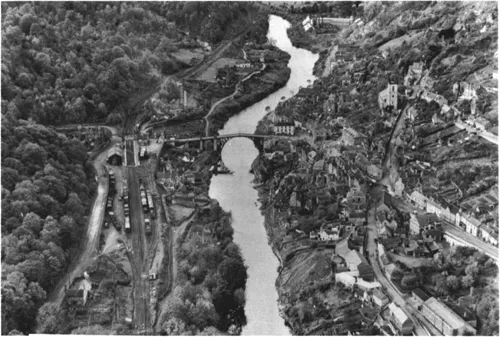

1.2 Aerial view of the Ironbridge Gorge (IGMT 1991.2294)

The history of the Gorge illustrates the processes of social and economic change which had their roots in the proto-industries of the seventeenth century, and which continued into the urban economy of the late nineteenth century. The traces of this history are imprinted on the landscape, and this book uses detailed local study to show how the landscape of the Gorge is not just a backdrop for technological achievement, but is also a rich source of evidence for the context and course of industrial change (fig. 1.2).

The book takes as its focus the landscape and communities of the Ironbridge

Gorge, and studies their origins, growth and decline. By working within these very narrow parameters, it has been possible to exploit the potential of landscape as a historical source, and integrate physical evidence with other material in an understanding of industrial change, examining not only how industrialisation came about, but also how it was sustained and developed.

A second and more practical thread to the work was the need for more information for planning decisions. The Ironbridge Gorge is one of less than a dozen World Heritage Sites which relate to the history of industry; it is also a Conservation Area which contains seven Scheduled Ancient Monuments and over two hundred Listed buildings. Yet despite this protection, planning decisions are often made without taking full account of the historical landscape. Elements within the landscape, such as the water-power systems, or early industrial housing, have been lost through failure to recognise their importance, and have not always been acknowledged and reflected in the system of protection. The mechanism for protecting archaeological sites is the Sites and Monuments Record held by the County Council, but it includes only a small proportion of the potential number of sites in the Gorge. Augmenting the Sites and Monuments Record was a prime justification for the work. However, it became clear that decisions needed more than just new archaeological points on the map. It was necessary to identify and present the links between these sites, to understand the historical structure of the landscape. In order to do this, a more complex type of survey was needed.

Landscape evidence

Economic histories of the Industrial Revolution commonly rely almost exclusively on documentary evidence; when physical evidence is used, it is often only to confirm or deny documentary sources, and is not usually used as a primary source in its own right. It is the landscape as a primary source of information which provides the central theme of this book, and its data are all those physical elements which remain or can be recorded, or which can be reconstructed from maps and documents. The principal sources for this study were therefore themselves landscape features—the shape and structure of the land, and the modifications made to it during its exploitation, the physical evidence of industry, buildings, architecture and settlement.

Our use of the term ‘landscape’ includes the widest range of features—from river to culvert, field to waste-heap, cottage to council-house—but the integrity and coherence of this industrial landscape have been respected by placing each distinct class of evidence firmly in its physical context and drawing out the spatial and chronological relationships between them.

The use of landscape evidence is not new. The evidence constituted by the landscape is familiar territory to local historians, following the pioneering work of W.G.Hoskins,1 and several other disciplines have as their subject components of the landscape: historical geographers draw inferences from the reconstruction of landscapes, and the spatial dimensions of social and economic conditions; urban historians study urban forms to analyse the development of towns, with a strong emphasis on social patterns; architectural historians take as their data building form; traditional archaeologists have used temporal as well as spatial data to look at evidence for change over time.

Each of these disciplines uses physical evidence—buildings, spatial organisation, archaeological deposits and urban form—but the industrial landscape in its own right can also constitute a class of historical evidence. Although there have been several studies devoted to the identification of the characteristic landscapes and features associated with particular kinds of industrial development, such studies usually select different landscapes to illustrate different stages of development, and do not consider how a single landscape changes. This study aims to develop an integrated approach to landscape study, and does so by bringing together different classes of evidence in the analysis of a single area as it changes through time. It begins to make links between different aspects of the landscape, and between different disciplines and data which can be used in its study.

The data for the study were gathered through an intensive archaeological survey of the Ironbridge Gorge. Unlike many such surveys, we did not confine ourselves to a single period, nor did we stop short at any particular date, analysing with equal attention the modern and ancient landscape. The survey involved the collection of data relating to buildings, plots and the landscape as a whole. This book is a direct product of that archaeological survey, and sets out to explore how landscape study could contribute to a better historical understanding of the Ironbridge Gorge.

Space, time and typology in landscape survey

Why should archaeology, a discipline traditionally associated with earlier segments of the past, be a suitable way of integrating different types of recent landscape evidence? Archaeologists have always had to deal with physical evidence for the past, and often in the absence of written records. The subject has evolved specialised techniques for deriving historical information from artefacts and sites. Three of the fundamental principles which underpin the treatment of such data are by no means unique to archaeology, and taken together they do provide a suitable framework for dealing with landscape evidence.

Recognition of patterns of change through time is basic to archaeology, and is enshrined in the concept of stratigraphy. Stratigraphy is in origin a geological principle, which was applied by excavators to the build-up of layers on a site. The same principle can be applied to landscapes and buildings. The landscape is a palimpsest of past activities, built one on top of the other. By stripping down the layers of this palimpsest, it should be possible to understand what can be seen today. In the same way, buildings change, and it is often only through adaptation that historic buildings remain standing. These changes are not just superficial alterations, but are part of the process of building itself. Recognising this cycle of change forms a key to understanding the historical processes which have shaped the landscape.

The second principle is that of setting information in its contemporary, spatial context. Spatial patterning is a geographical concept, which again is applied in archaeology. The concept of ‘context’ is the basis of archaeological excavation, in which the information value of a find lies more in where it is found than in what it is.2 A coin may have no value to an archaeologist unless it can provide information about the context in which it was found. Context in the industrial landscape may be the land around a building, the relationship of a furnace to its water-power system, or the line of a coal outcrop. Identifying ‘context’ is thus a way of linking the buildings and individual industries with their wider landscape setting.

The third concept is the idea of the typology. The earliest notions about prehistory were based on the recognition that artefacts could be grouped by materials, and this concept has remained a valuable approach to the classification of objects.3 In the case of a landscape, the objects might be buildings, for example. Buildings themselves are only rarely documented, and the date, builder and occupier are not often known. But through systematic quantitative and comparative analysis (discussed in more detail below) it is possible to identify significant patterns of variation through time. These patterns can help not only in the dating of local buildings, but also in understanding the social, economic and cultural contexts of their use.

By applying the basic archaeological principles of time, space and typology, we hoped to be able to use landscape data in a more rigorous fashion than had hitherto been possible. But in order to use these concepts to make a coherent analysis of the patterns which we observed in the landscape it was necessary first to refine the field techniques of archaeology to make them more applicable to the particular problems posed by the industrial landscape.

The first difficulty was the traditional archaeological concept of ‘the site’, which is the usual way of collecting information. There were several problems with the idea of the site understood as a closely delineated point on a map; the first was that it effectively divorced a building or industry from its wider spatial setting. Second, selection of specific sites risked discriminating between categories of information and selecting only the most interesting. For industrial sites where operations are linked to complex networks of transport or power, it can be difficult to draw boundaries. Finally, the idea of a site as a single entity was not easy to sustain where every building or industry seemed to have gone through a complex cycle of reuse and change.

Therefore another means of collecting information was adopted—plot survey.4 Plots are the basic units in which all land is divided, described and conveyed; they may be of any shape and size and range from a tiny garden to a large area of open heath. They are not just arbitrary divisions of land, but have a historical significance. They reflect continuity in the organisation of land, and the way land is divided; plots can indicate the circumstances in which a building was built, or show changing patterns of agriculture. Plot boundaries may also be important in the recognition of past processes of land development. Plot survey was also a way of ensuring total, rather than selective, coverage of the landscape.5

The plots shown on the 1902 Ordnance Survey Map (fig. 4.2) were taken as the basis for the survey. The choice was practical since full coverage was easily available, and also made sense in the field in that the map included the standard-gauge railways which had radically transformed the landscape in the late nineteenth century.6

A single plot might contain many different features; during survey numbers were therefore assigned to all identifiable features within each plot, in order to ensure that equal weight was given to different types of information. The archaeological technique of a stratigraphic matrix was used to organise this information chronologically, to sequence and phase complex sites.7 The value of this technique in a landscape context was demonstrated particularly well in the limestone industry of Benthall Edge, where over a hundred quarries, approach roads and spoil heaps were numbered and recorded. A diagram was constructed showing their stratigraphic relationships, and from this it was possible to identify the different phases of quarrying from the medieval period through to the twentieth century, as well as transport routes, and the type of stone quarried, despite the minimal quantity of documentary evidence. The matrix was thus a way of analysing change through time in the most rigorous manner possible.

Housing as a historical source

The survey which forms the basis for this study also sought to develop the use of housing as a historical source. Settlement patterns and building design can contribute to understanding the process of industrialisation, since they are a direct product of patterns of economic and social change. The location of housing, and the patterns of its development, map out a wider land use, influenced both by the presence of industry and by the organisation of landholding. The distribution patterns, types of development and certain architectural characteristics found in the Gorge themselves provide evidence for the process and structure of industrialisation.

This study used the phasing, distribution and design of buildings as evidence for the history of industrialisation and the creation of an industrial way of life. It aimed to identify those features characteristic of the landscape of industry—its patterns of settlement, its housing types and their significance—and to show how industrialisation took place in the spheres of architecture and building design.

In carrying out this programme of research, the plot-based approach discussed above in the context of industrial archaeology was also used. This meant that building was considered first as a particular land use, and spatial context was given due attention. And since it was the history of the plot, rather than a conventional architectural history, which provided the starting-point for research, no chronological cut-off date was adopted, with the result that any building of whatever age or status was considered. In addition, buildings which no longer survived were recorded wherever possible, using a range of documentary sources. Previous buildings on a site, and the several phases of development characteristic of many of the buildings in the area were also taken into account. The histories of buildings themselves were registered, thus considering not only the moment of construction, but also the patterns of use which modified and conditioned the survival of the buildings in the area.

Initially surveyed by parish or local area, the discussion in this book presents a synthesis of the results across the whole Gorge. The data were analysed first by considering the distribution of settlement and its characteristic forms. The study looked at the spatial relationships between buildings and industry as evidence for the organisation and control of land use, using the chronology of settlement to help map out the major phases of industrial development. The forms of settlement provide evidence for the changing structure and organisation of the industrial economy and society, as small and isolated settlements were gradually drawn together in an urban framework.

The study also considered patterns of development by looking at the relationship between buildings, and charting the distribution of single dwellings, pairs and terraces. These relationships provide direct evidence of the organisation of development and the processes which shaped the landscape of building. Thus the pattern of building associated with industrialisation began as a scatter of single buildings but soon encompassed the development of coherent terraces. This pattern of change came about through the piecemeal expansion of buildings as well as the deliberate building of groups, and is indicative of the location of resources in the economy and the emergence of a property market.

The codification of design and the architectural development of building also reflected the course of industrialisation: as a commitment of resources, buildings give at least some indication of a distribution of wealth. The large numbers of houses built by professional craftsmen for a population that was not engaged in agriculture in the early eighteenth century suggest the extent of a prosperity based on mining and manufacture; the gradual diversification of housing types suggests the emergence of a distinctive social hierarchy, especially during the nineteenth century. In housing, as in industry, development was constantly shaped by the inheritance of the existing building stock, and new architectural forms were themselves largely derived from existing models.

A comparative and quantitative study of buildings in the area identified the design processes used in building, and used this to classify the major local building types. There are two principal design processes for building: one relies on pattern books or the role of an architect, the other, which is more traditional or vernacular, appeals to and modifies the design embodied in existing buildings. Each process of design must work with a given development type and architectural vocabulary which comprises all the elements of building—constructional technique, plan, sectional form, detail and decoration. The role of traditional methods of design in the development of the Gorge is underscored by the identification of a common form and configuration of elements in many buildings, even where size and number of units in the plan varies. These similarities suggest that such buildings were built with reference to a common model. In other buildings, by contrast, the disposition of elements appears unique.

Conventional design methods could produce widely different types ...