eBook - ePub

Marine Management in Disputed Areas

The Case of the Barents Sea

- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

As world natural resources diminish and the necessity of protecting our environment becomes critical, the need for efficient marine management increases. However, marine boundaries are not easily defined and in disputed areas the prospect of sound management is difficult. The Barents Sea is a perfect example of this. Despite being rich in living resources, the area remains under developed and its eco-system is under growing threat. This inefficient management is largely due to two legal disputes, both of which involve the USSR. Marine Management in Disputed Areas examines the complicated management of the Barents Sea, as well as offering a detailed analysis of two highly sensitive legal disputes.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Marine Management in Disputed Areas by Robin Churchill,Geir Ulfstein in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction

AIMS AND SCOPE OF THIS BOOK

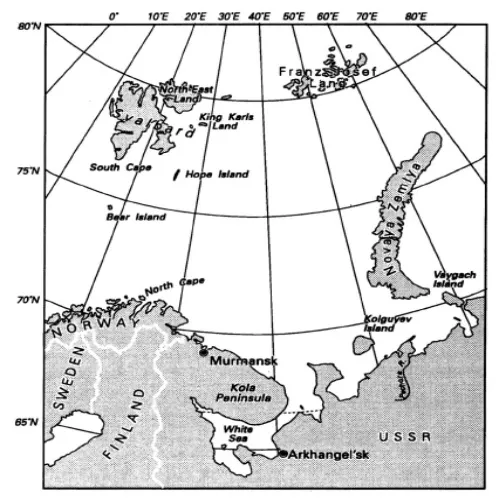

The broad aim of this book, as one in a series partly concerned with the management of particular seas, is to look at the management of the natural resources of the Barents Sea. As the object of a study in regional marine resource management, the Barents Sea (see Map 1.1) is unusual in a number of respects. First, it has only two riparian states, Norway and the USSR, which for most of the time since 1945 have belonged to opposing military alliances. Second, the development of a proper regime for managing the natural resources of the Barents Sea has been greatly affected and hindered by two long-standing unresolved legal questions. The first of these is the location of the boundary between the maritime zones of Norway and the USSR: without an agreed boundary the proper management of resources is clearly made more difficult, and there is obviously more potential for conflict and friction between the riparian states. The other important unresolved legal question is whether the Treaty concerning the archipelago of Spitsbergen of 1920 (with its regme of equality of treatment for all its parties in the exploitation of the resources of Svalbard)1 extends to the maritime zones of Svalbard beyond its territorial sea. If the Treaty does so extend, then all forty or so states party to it will have an equal right to exploit the resources of those zones: on the other hand, if the Treaty does not so extend, the exploitation of those resources will be the sole prerogative of Norway. Finally, the Barents Sea is unusual in the degree to which military and strategic issues influence the management of its natural resources: such issues also have a very important bearing on the possible resolution of the two legal questions just referred to.

Within the broad aims of this book just described, the authors have chosen to focus in particular on the two unresolved legal questions referred to above. They have done so for two reasons. First, these are the issues relating to the management of the natural resources of the Barents Sea which the authors, both of whom are lawyers, are most competent to discuss. Second, and perhaps more importantly, the authors feel that these two outstanding questions of the maritime boundary and the area of application of the Svalbard Treaty have not received the kind of extended, rigorous, detached legal analysis that they deserve: most of the existing literature on these questions (much of which is not in English) is either highly partisan and/or written not by lawyers but by political scientists. Chapters 2 and 3 attempt to remedy this deficiency by offering what is hoped will be considered a thorough, sustained and reasonably detached analysis of these two questions and some suggestions as to what the answers to these two questions might be.

Map 1.1 The Barents Sea

The resources of the Barents Sea which have so far been the most important in practice are its living resources. The regime that has evolved for their management is analysed and subjected to critical evaluation in Chapter 4. While the focus, as in the preceding two chapters, is predominantly legal, the authors have attempted, as in those chapters, to place discussion of the legal issues in their proper political and economic context. The other major, though currently only potentially rather than practically important, natural resources of the Barents Sea are oil and gas. Chapter 5 discusses developments so far in the exploration and exploitation of these resources, and gives a brief account of the regime that currently governs these matters. This chapter also discusses the question of controlling pollution from future offshore development of oil and gas. This is the only discussion of pollution in the book. The reason why there is no further discussion is because the Barents is not a particularly polluted sea (although the same is not true of the adjoining Kola Peninsula, where pollution from its mining industries has become a serious problem, causing damage not only to the peninsula but also to adjoining land areas in Finland and Norway). Other reasons for limiting the discussion of pollution are that much of what pollution there is in the Barents Sea originates from outside the area and that there is no specific legal regime for pollution relating to the Barents (though of course many of the general marine pollution agreements do cover the Barents Sea).

The aim of the present introductory chapter is to give sufficient background information to facilitate understanding of the legal questions discussed in Chapters 2 and 3 and the management issues discussed in Chapters 4 and 5.This chapter begins with a description of the geography and oceanography of the Barents Sea. It then turns to give some idea of the enormous wealth of the living resources of the Barents Sea and an indication of the possibilities for exploiting oil and gas. This is followed by a brief account of the military and strategic significance of the Barents Sea, and of uses of the Barents Sea other than for military and resource purposes. The final part of the chapter outlines the framework of jurisdiction (that is, the different maritime zones) in the Barents Sea.

While much of the material in this book will be predominantly of interest in Norway and the USSR, the issues discussed do nevertheless have a much wider interest, not just to academic students of marine resource management, but also in a very real practical sense. All forty or so parties to the Svalbard Treaty, which include all the major developed states, have an interest, not to say a potentially very important economic stake, in the outcome of the question as to whether the Treaty applies to the maritime zones of Svalbard beyond its territorial sea, both in terms of fisheries interests and oil and gas potential. In addition, irrespective of the outcome of this question, a number of third states have vessels fishing regularly in the Barents Sea, and such states and their vessels are directly concerned with the regime for managing the living resources of the Barents Sea.

Before we turn to the subject-matter of this chapter outlined above, the necessary background information on the Barents Sea, its resources and uses, we must first seek to try to define the area and boundaries of the sea we are dealing with.

DEFINING THE BARENTS SEA

It is difficult to define seas with great precision, except for those seas that are virtually enclosed, like the Mediterranean and the Red Sea. Nevertheless, there is a fairly generally accepted definition of the Barents Sea, whose use is endorsed by the International Hydrographic Bureau. This definition is as follows. To the south the Barents Sea is bounded by the mainland coasts of Norway and the USSR, to the east by the large Soviet archipelago of Novaya Zemlya, and to the north by the archipelagos of Franz Josef Land and Svalbard, belonging to the USSR and Norway respectively. In the west the Barents meets the Greenland and Norwegian Seas, the conventional dividing line being taken as the line running from the South Cape (on Svalbard), through Bear Island (Norwegian) to the North Cape on the Norwegian mainland. Thus defined, the Barents Sea is about 1.4 million square kilometres (about 542,000 square miles) in area.2

OCEANOGRAPHY

The Barents Sea is comparatively shallow, only about half being deeper than 200 metres. The average depth is 229 metres.3 South of Bear Island the sea-bed plunges to about 500 metres in Bear Island Trench, and there are a number of smaller troughs or trenches—the South Cape, North and North-east Trenches. Geologically speaking, the whole of the bed of the Barents Sea is continental shelf, part of the world’s largest continuous continental shelf, extending from the Barents Sea in the west to Siberia and the Chukchi and Beaufort Seas in the east, and northwards several hundred miles north from Norway, the USSR, Alaska and Canada. This continental shelf also extends somewhat to the west of the western boundary of the Barents Sea described above.4

Thanks to the Gulf Stream, the Barents Sea and its coasts are significantly less cold than all other areas at the same latitudes. As a result, there is much less ice than in other sub-Arctic seas. The south-west part of the Barents Sea, from just south of Bear Island to the eastern end of the Kola Peninsula, is free of ice all the year round. The remainder is covered, for at least part of the year, with ice in various forms (drift-ice, pack-ice, ice ridges and icebergs), although in the summer the whole of the Barents south of a line between Svalbard and Novaya Zemlya is free of ice and in September, the best of the summer months, it is possible to sail to Franz Josef Land. Most of the ice in the Barents Sea is of local origin, though there is some movement of ice from the Polar Basin and Kara Sea into the Barents Sea. Most ice is less than one year old, and apart from ice ridges (which on average have ice keels of 12 m) and icebergs, does not exceed one metre in thickness.5

Tidal amplitude varies greatly, from 13 feet (4 m) at North Cape and 30 feet (9m) at Strait Gorlo on the White Sea, to 5 feet (1.5 m) at Svalbard and 2.6 feet (0.8 m) in the vicinity of Novaya Zemlya.6

The climate is sub-Arctic, with winter air temperatures averaging -25°C in the north and -5°C in the south-west, and summer air temperatures averaging 0°C and 10°C, respectively. Annual precipitation is 20 inches (500 mm) in the south, but only half that in the north.7 The Barents lies in the path of warm cyclones from the North Atlantic and cold anti-cyclones from the Arctic, producing very unstable climatic conditions and some of the most storm-ridden stretches of sea in the world.8

GEOGRAPHY

The Barents Sea takes its name from the Dutch explorer, Wilhelm Barents, who made a number of expeditions to the area in 1594–6. The Barents Sea was, however, known and used long before the voyages of its eponymous explorer. It is likely that prehistoric man lived on its shores, as rock carvings have been discovered at Alta, some miles south-west of the North Cape, which are believed to be 5–6,000 years old. In historic times, there is little doubt that the Barents was sailed on extensively by the Vikings, who are thought to have known about Svalbard in the twelfth century. From the thirteenth century onwards there was a vigorous seaborne trade between North Norway and Northern Russia. In the sixteenth century came the Dutch, who ‘rediscovered’ Bear Island and Svalbard in 1596. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries there was large-scale hunting of walrus and whales in the seas around Svalbard by British, Dutch, French, Hanseatic, Danish, Norwegian, Russian and Spanish vessels. From the nineteenth century onwards, as we will see below, the Barents Sea and its bordering coasts have been subject to a wide variety of economic and other activities.

We will now turn to say something about each of these bordering coasts, mainland and insular, beginning with the mainland coast of Norway and moving clockwise around the Barents Sea.

The coast of Norway bordering the Barents Sea runs from the terminus of the Soviet-Norwegian land border on the shores of Varangerfjord westwards to the North Cape. This coastline, often comprising steep cliffs, is deeply indented, being penetrated by a number of large fjords. Unlike most of the Norwegian coastline, the easterly part of the Barents coast, the Varanger and Nordkinn peninsulas, is almost wholly devoid of offshore islands: only in the vicinity of the North Cape (which itself is on an island) do islands start to become more numerous. This part of Norway is thinly populated. The entire population of the county of Finnmark, which includes not only the Barents Sea coast but also the coast some 130 miles south-west of the North Cape, as well as the adjacent inland areas up to the frontiers with the USSR and Finland, is only 74,000. Most of this population lives in small scattered, isolated communities on the coast. Fishing forms the backbone of the economic activities of these communities, although around Kirkenes, close to the Soviet border, there is also iron-ore mining. Inland from the coast live the Lapps, whose livelihood is largely based on reindeer: there are also some Lapps living on the coast who make a living from sea fishing.

Some 220 nautical miles north of the North Cape lies Bear Island. This small, isolated, pear-shaped island belongs to Norway, but legally is part of Svalbard rather than mainland Norway, the significance of which will become apparent shortly. Bear Island is only 178 square kilometres in area. It has no permanent population, although there is a weather station which is staffed all the year round by teams of meteorologists. Otherwise, other scientists spend time on the island, as does the occasional hunter.

Some 130 nautical miles north of Bear Island lies the South Cape, the most southerly point of the Svalbard archipelago. The latter comprises a number of large islands—Spitsbergen (formerly called West Spitsbergen), North-east Land, Barents Island and Edge Island—together with a large number of smaller islands, islets and rocks, making a total area of 62,400 square kilometres (roughly the size of Belgium and the Netherlands combined). The archipelago belongs to Norway, but as we shall see in more detail in the next chapter, the Treaty of 1920 that gave Norway sovereignty over Svalbard also provided that the nationals of the other forty or so states party to the Treaty were to enjoy the same rights as Norwegian citizens in relation to economic activities, including mining, hunting and fishing. About two-thirds of Svalbard is permanently covered by ice and in several places glaciers reach the sea. Land forms are largely Alpine, and much of the coast is indented by fjords. There are no indigenous inhabitants on Svalbard. Most of the thousand or so Norwegians who live on Svalbard are engaged in coalmining, producing about 400–450,000 tonnes a year. Coal-mining, which began in 1899, is the major, and indeed— apart from a few individuals hunting animals for their furs, and tourism in the summer months—the only, economic activity. The Russians also engage in coalmining, producing about the same amount of coal as the Norwegians, but with two or three times the population. The USSR is the only party to the Treaty currently exercising its rights to engage in economic activities on the same footing as Norway,9 although since the late 1960s oil companies from other states parties (and Norway) have been exploring for oil, although so far without making any commercial finds. Other minerals found on Svalbard, though again not (yet) in commercial quantities, include iron, lead, copper, zinc, marble, gypsum and asbestos. There is also a certain amount of scientific research on Svalbard, undertaken by scientists from many of the states party to the 1920 Treaty. Finally, the waters off Svalbard are rich in fish stocks and support a large commercial fishery: none of the vessels engaging in this fishery operate from Svalbard, however. More is said about this fishery on pp. 9–12, when discussing the resources of the Barents.

To the east of Svalbard lies another archipelago, Franz Josef Land. This comprises some 191 islands, arranged in three main groups, occupying an area of 16,134 square kilometres. Franz Josef Land consists mainly of low-lying plateaux, 85 per cent of whose surface is permanently covered by ice. The archipelago became part of the USSR in 1926. Apart from meteorologists working at a number of permanent weather stations, there are no people living on Franz Josef Land.

Some 200 nautical miles south of Franz Josef Land lies the northern end of the large Soviet archipelago of Novaya Zemlya. The archipelago consists of two very large islands, Severny and Yuzhny, separated by the very narrow Matochkin Shar strait, together with several smaller islands. The archipelago extends for about 2,000 kilometres along a north-east-south-west axis and is about 82,600 square kilometres in area. Novaya Zemlya is a continuation of the Ural Mountains system, and therefore is largely mountainous. Over a quarter of its land area is permanently covered by ice. The only people living on Novaya Zemlya are a number of scientists working at meteorological stations. The original indigenous population, some 400 Samoyeds (or Nenets), were forcibly removed during the 1960s when Novaya Zemlya was used for the atmospheric testing of nuclear weapons. Testing has recently been resumed, although it is now underground.10

Separated from the southern end of Novaya Zemlya by the fifteen-mile-wide Kara Gates Straits is the large island of Vaygach, which in turn is separated from the mainland by the much narrower lugorskii Shar Strait. From this point the generally low-lying and sparsely inhabited Soviet mainland coast, ice-locked for much of the year, runs westwards to the Kanin Peninsula, the eastern entrance to the White Sea. North-east of the Kanin Peninsula lies the large island of Kolguyev (about 3,500 square kilometres) the only island of any size, apart from the archipelagos forming its periphery, in the Barents Sea. There is a fair-sized oilfield on the island from which commercial production has recently begun (see below, p.).

The White Sea is excluded from the definition of the Barents Sea given earlier. Thus the final stretch of coastline to be considered in this brief geographical overview of the Barents Sea is the Kola Peninsula, lying between Cape Sviatoi Nos, the western entrance point to the White Sea, and the Soviet-Norwegian frontier. The Kola Peninsula is by far the most heavily populated and most economically active and diverse of the Barents Sea’s coasts. Much of the Kola Peninsula coastline is fairly straight, but towards its western end it is penetrated by a number of fjord-like indentations which provide several excellent sheltered harbours which are free of ice all the year round. These harbours, including that of Murmansk, are the home of the USSR’s Northern Fleet, its largest navy, about which more is said below in the section on the strategic significance of the Barents Sea, and the USSR’s largest fishing fleet. Apart from these maritime activities, the Kola Peninsula is also the site of mining for nickel, apatite and iron ore. Altogether these economic activities support a population of about one million on the Kola Peninsula, of which about half live in or very close to Murmansk.

NATURAL RESOURCES

The Barents Sea has one major actual natural resource and one potential natural resource of significance. The former is fish: th...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Illustrations

- Preface

- 1: Introduction

- 2: Application of the Svalbard Treaty to Maritime Areas

- 3: Boundary Delimitation in the Barents Sea

- 4: Fisheries Management and Access to Fishery Resources

- 5: Offshore Petroleum Activities

- 6: Conclusions

- Notes

- Bibliography