1 The Mediterranean region in its context

I have loved the Mediterranean with passion, no doubt because I am a northerner like so many others in whose footsteps I have followed.

(Braudel, 1975: 16)

A number of authors have produced geographies of the Mediterranean region (e.g. Walker, 1960; Houston, 1964), historical geographies of the region (e.g. Semple, 1932; Grant, 1969; Delano Smith, 1979) or even what might be described as geographical histories – as in the case of the magnum opus of Braudel (1975). The older of these texts fit firmly within the regional geography perspective, in attempting to produce a descriptive explanation of the characteristics and peculiarities of the region. Braudel and Delano Smith, on the other hand, aim to provide explanations of how the landscape has structured human life and history. These explanations are the backdrop of the longue durée, to use Braudel’s term. Horden and Purcell (2000) have recently tried to expand Braudel’s approach over a much longer time span.

However, we should take care not to consider this backdrop as operating in a one-way direction. Equally important is the impact humans have had – and continue to have – on the landscape and other elements of the environment. There are a number of books that deal with this impact, for example, Thirgood’s (1981) and Meiggs’ (1982) discussions of the link between forests and human activity, and McNeill’s (1992) masterly overview of the impacts of settlement on the Mediterranean mountains. In some respects, Hughes (1994) can be thought of as an updating of Semple in that the Classical world is considered in its interaction with the environment. More recently, there have also been two introductory, edited review volumes – King (1997) and Conacher and Sala (1998) – that have dealt with this interaction, but with a focus more on current environments and environmental problems.

It is a central thesis of this book that we are made by the landscapes around us. Our everyday activities are limited by environmental constraints and our attempts to overcome them. Furthermore, modern attempts to live within the environment are controlled by the past development of that environment. This development may be driven by climatic change, internal mechanisms of evolution or the effects of human activity. However, the extent to which any of these are separable on long timescales is indeed debatable. An important consequence of these interlinkages is that understanding where we are today means understanding the ways in which the environment has developed in response to them. To a certain extent, but by no means always, a better understanding developed in this way can help us deal with current and future issues relating to the Mediterranean environment. In this sense, the Mediterranean region is taken as an example of an approach that is generally applicable in any environment. One of the advantages of taking this particular example is that it has had such a long history of environmental interactions, as we will show.

The region is also home to a rather sensitive set of environments, and the timescales over which human and other impacts can affect them vary over a very wide range – from a matter of days to millennia. An appreciation of this sensitivity allows us to take an appropriate viewpoint towards ongoing and future issues of environmental impact. Although human development of the environment will continue to occur – slowly at times, but with periods of very rapid change – we are now more than ever in a position to do so in a responsible way. This is not to say that the past inhabitants had no understanding of how their environment worked – clearly, this is not true – but the level of detail available now, together with an understanding of some of the more important feedback mechanisms and levels of complexity, means that we are much better informed about how environmental systems work. Some of the detail of this understanding in terms of landscape-forming and other environmental processes is therefore one of the key elements of the book. By continually testing our understanding by a process of abduction with past data (Baker, 1998) is one way that we can provide sufficient information from sufficiently extreme conditions to be confident over all appropriate timescales, not just those from our anthropocentric present.

One perspective developing from this view would be to suggest that we should engineer the environment to exploit it in as intensive a way possible while minimizing any ‘negative’ impacts. Such a perspective would be to miss the point. It must be realized that there are a whole series of issues relating to the quality of life – the aesthetics and other ‘intangibles’ of our surroundings – that cannot be incorporated into such evaluations. The fact that our actions may affect the environment – and thus our descendants – for millennia to come means that we should proceed with the knowledge of what those actions could produce. Thus, the conflicting personal, political, economic and social needs that lead to individuals and societies acting on the environment in a particular way must clearly be balanced in this perspective. One argument that is commonly heard is that we should not worry too much about the environment, as it will probably recover (eventually) from any particular negative human impact. This assertion is almost undeniably true. What the experience of the past shows is that the particular society that caused the problem did not necessarily recover.

It is our aim here, then, to attempt to provide the best explanation possible for understanding the Mediterranean environment as an example of environmental interactions everywhere (some not in as far an advanced state as that in the Mediterranean because of the shorter history of human impacts). This explanation will involve looking at the mechanisms by which the environment operates over timescales ranging from millions of years to the fall of raindrops within individual rain storms. The landscape is a function of this range of slowly operating forces and periodic catastrophic change. We will incorporate human activity and its effects on a range of timescales. The mechanisms and effects of human activity are also spread over a range of rates of operation. The data available necessarily mean that the picture will be more hazy for the earlier periods. Because of the sensitivity of Mediterranean environments, however, they have become an important focus for work by environmental scientists, and thus we have a level of detail on ongoing problems that is almost unparalleled. We can thus aim to let the past help us understand the present, and the present to understand the past.

What and where is the Mediterranean?

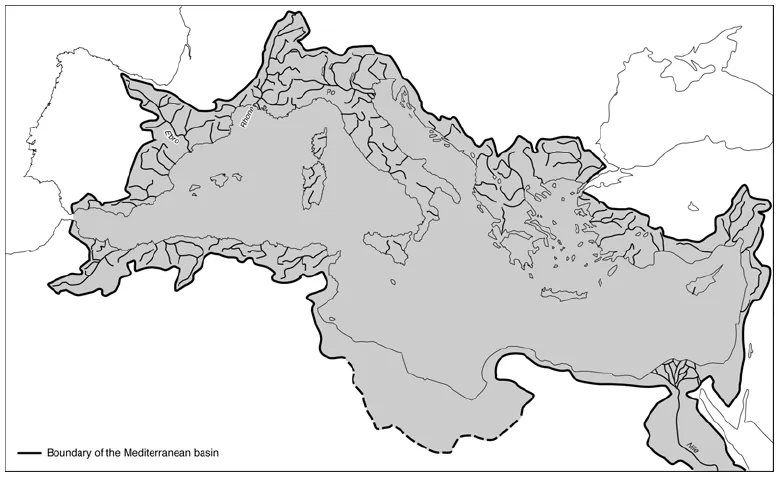

As we shall see in Chapter 2, the Mediterranean is a relative newcomer to the Earth’s landscape. The closure of the eastern seaway of the Tethys Ocean did not occur until about nine million years ago, bringing about the basic physiography as we see it today. The catchment that drains into the Mediterranean Basin (Figure 1.1) is thus an area that continues to develop and work headwards (see Lewin et al., 1995 for examples of drainage-basin evolution). In one sense, this area could be considered as the Mediterranean, but the nature of the topography – which is intimately linked with the geological history of the region (see Figure 2.10) – means that such a definition excludes many areas that share important characteristics with the coastal zone. Furthermore, areas of northern Africa, where aeolian activity dominates fluvial, can only be very poorly defined in this way.

Figure 1.1 The catchment of the Mediterranean Basin

Source: Reproduced in Grenon and Batisse (1989).

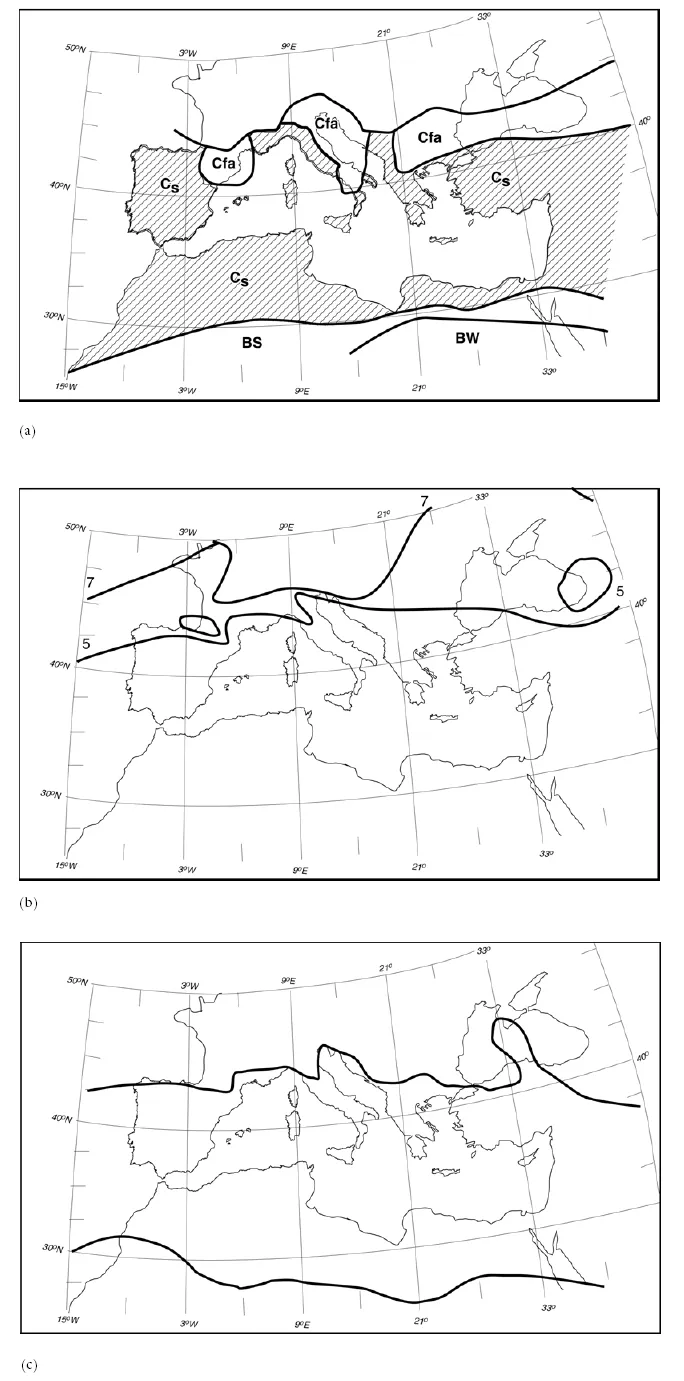

It has also been common to define a region of ‘Mediterranean climate’. The climate we currently define as Mediterranean is a much more recent phenomenon, as we will discuss in Chapter 3. It has only essentially been in place for the last million years or so, and even then has fluctuated dramatically as a result of the large glacial–interglacial cycles that have affected the globe. The result of these fluctuations has been that present Mediterranean conditions have only been effective for a small proportion of that time. The actual definition of boundaries according to the simple climatic classifications varies quite markedly. Most areas of the Mediterranean fit into the dry or warm, temperate climate zones according to the Köppen scheme (Figure 1.2a). However, it has been demonstrated that the boundaries produced by the Köppen scheme are highly sensitive to the data set used to define it. Emberger proposed simple boundaries to the climate region using an index calculated by dividing the summer rainfall in mm by the average maximum temperature of the warmest month in degrees Celsius. A value of five delimited the Mediterranean climate zone, with seven being the boundary of the sub-Mediterranean zone (Figure 1.2b). Although this scheme works well for the northern part of the basin, it is completely inappropriate for the south, delimiting the limits of the Mediterranean zone in the middle of the Sahara. Daget (1980) defined a compromise based on the ratio of warm-season to cold-season precipitation and the summer concentration of temperatures. The ‘Mediterranean Isoclimatic Area’ (AIM in French) is thus defined, providing a better fit to the region as a whole (Figure 1.2c), including the semi-arid zones of North Africa. However, although this is probably the best definition of the Mediterranean climate, there is still a feeling that it is derived empirically, rather than being based on any good a priori reasons. Furthermore, as with the other schemes, it extends well into the interior of eastern Asia, and thus incorporates areas that we would tend to exclude from true Mediterranean climates. Overall, then, such simple schemes tend to be unsatisfactory. Perhaps the best definition of the Mediterranean climate is with a set of common factors but with a strong sense of variability over a number of different timescales, and encompassing a range from arid, through semi-arid to sub-humid conditions.

Figure 1.2 Climatic definitions of the Mediterranean zone: a. Kӧppen’s classification scheme (where B indicates a dry and C a warm temperate climate, f sufficient precipitation in all months, s a dry summer season, S a dry winter steppe, W a dry winter desert, a the mean temperature of the warmest month >22°C, and b the warmest month with a mean of <22°C, but at least four months with means >10°C); b. Emberger’s definition of the Mediterranean and sub- Mediterranean zones; and c. Daget’s ‘Mediterranean Isoclimatic Area’

Note

See text for further details.

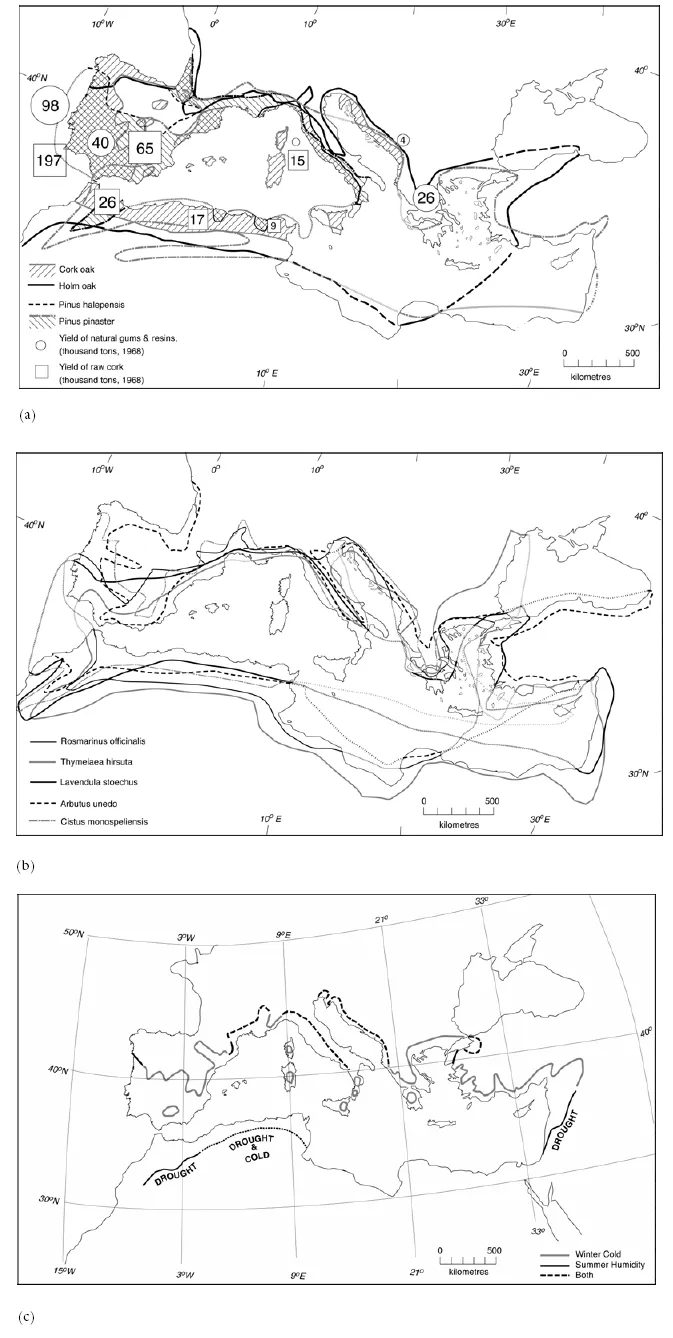

Third, a ‘typical’ Mediterranean vegetation is often used as a definition of the region, the rationale being that the vegetation should reflect the dominant environmental conditions. If this is so, then such a definition suffers from many of the problems relating to the climate definition. There are also important lags in terms of the response time of vegetation to imposed change, so that employing it as a means of defining climate change is also problematic. As will be discussed in Chapter 4, there are many reasons why the main species around the region are not necessarily distributed at the present time in the same way as they have been during previous interglacials. The tree species that are commonly used, such as holm oak or aleppo pine, tend not to have a circum-Mediterranean distribution, and the only species that do are effectively the matorral species, which are generally found as a consequence of disturbance (Figure 1.3). The olive is very commonly used as an indicator species, but, if anything, this use is the most problematic. Its environmental limits of distribution are controlled by a number of different factors, which have different effects in different regions. The distribution of the olive is also very strongly controlled by human activity in the past and present, as we shall see in detail in Chapter 10. An excellent background to Mediterranean vegetation patterns is also given by Allen (2001).

Figure 1.3 Distributions of ‘characteristic’ Mediterranean plant species: (a) holm oak and aleppo pine; (b) matorral species; and (c) olive (with indications as to the source of the limits of its environmental range), reproduced by permission of Hodder Arnold

Source: a and b after Beckinsale and Beckinsale (1975); c after Daget (1980).

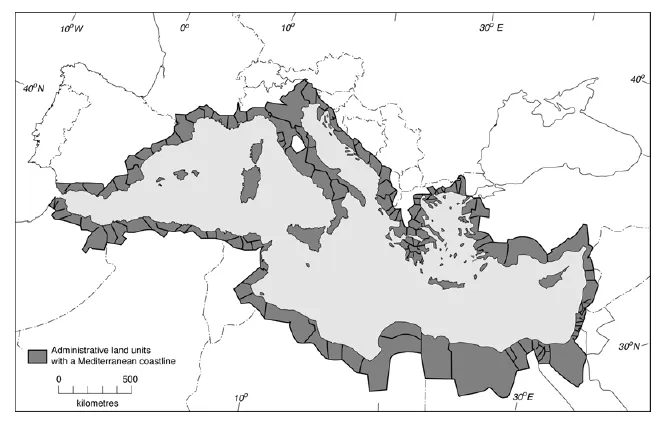

Other authors have chosen to use country boundaries or other political or administrative boundaries (Figure 1.4). Such a definition is also somewhat artificial. If the smallest administrative level is chosen, large areas of the hinterland that are vital to Mediterranean socioeconomic systems are cut off. These levels also differ from country to country. If the country level is chosen, then clearly some areas are included that clearly do not share Mediterranean characteristics of any sort – northern France and the south of Libya and Egypt being the clearest examples here. One could also use a reductio ad absurdum argument by using past examples – including the parts of India conquered by Alexander the Great, or Britain as a Roman conquest (although the media enjoy the parallels of Britain enjoying a ‘Mediterranean’ climate under future scenarios of enhanced greenhouse-gas activity!). The administrative units also differ vastly according to the country chosen (reflecting in part the different population densities and their spatial distributions).

In summary, none of these simple definitions of the region are really satisfactory. All include important elements and exclude others. None so far has included Portugal, for example, despite the fact that it shares a number of common traits with the rest of Iberia and the region. The Mediterranean has been a cross-roads, both physically and socially. It has marked a place where plate boundaries have met, air masses mixed, plants combined from different regions and evolved into endemic species, and people have developed new ways of life and spread them to Europe and beyond. Subsequently, the interactions with the wider world have had significant impacts on the peoples and environments of the region. As noted above, it is partly because of this rich and varied heritage that the Mediterranean is an interesting and useful environment to study. In this book, then, we will employ a rather fluid definition of the region, employing climatic, vegetational, environmental and cultural definitions as appropriate. It is by looking at the series of commonalities that arise, and the situations in which they do not work, that we can hope to learn more about the environment and the people that have occupied it.

Figure 1.4 Definition of the Mediterranean zone by the Blue Plan according to modern administrative boundaries with some frontage on the Mediterranean coastline

Source: Grenon and Batisse (1989), reproduced with the permission of Oxford University Press.

Current environmental problems in the Mediterranean

As we shall see from Chapter 14 onwards, there are a number of significant problems that currently affect the Mediterranean region. Some of these problems are Basin-wide, while others affect specific regions. The underlying driving mechanisms for these problems are the everincreasing numbers of people living in the region, and to a certain extent population increases elsewhere in the globe. There is a scarcity of water for drinking, for irrigation and for industry. The source of the scarcity is the underlying nature of the Mediterranean climate, with long periods of hydrologic deficit and high levels of interannual variability in rainfall, but long periods of over-exploitation have exacerbated the issue. Land degradation is occurring because of both intensive use of the land, and its abandonment. The source of these changes are ultimately the long history of settlement and the development of settlement patterns in the region. New problems are also arising, due to the use of new technologies but also the evolution of new political structures, relating to changes on the European and global scales. The attractiveness of the region is also potentially forming part of its downfall. The very large, and continuously increasing, numbers of tourists that visit the region every year have led to a variety of deleterious developments, and increasing pressure on scarce resources such as water, and adding to the pollution of the area. All of these issues are enhanced by the sensitivity of the various parts of the environment, as discussed in Chapters 3 to 8. Given the extent and increasing rate of pressure on these landscapes, it is therefore fundamental that we put our understanding to good effect.

The long history of environmental issues in the Mediterranean region

As sugg...