eBook - ePub

Malaysia, Modernity and the Multimedia Super Corridor

A critical geography of intelligent landscapes

- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Malaysia, Modernity and the Multimedia Super Corridor

A critical geography of intelligent landscapes

About this book

Based on fieldwork in Malaysia, this book provides a critical examination of the country's main urban region. The study first provides a theoretical reworking of geographies of modernity and details the emergence of a globally-oriented, 'high-tech' stage of national development. The Multimedia Super Corridor is framed in terms of a political vision of a 'fully developed' Malaysia before the author traces an imagined trajectory through surrounding landscapes in the late 1990s. As the first book length academic analysis of the development of Kuala Lumpur Metropolitan Area and the construction of the Multimedia Super Corridor, this work offers a situated, contextual account which will appeal to all those with research interests in Asian Urban Studies and Asian Sociology.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Malaysia, Modernity and the Multimedia Super Corridor by Tim Bunnell in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Geography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Introduction

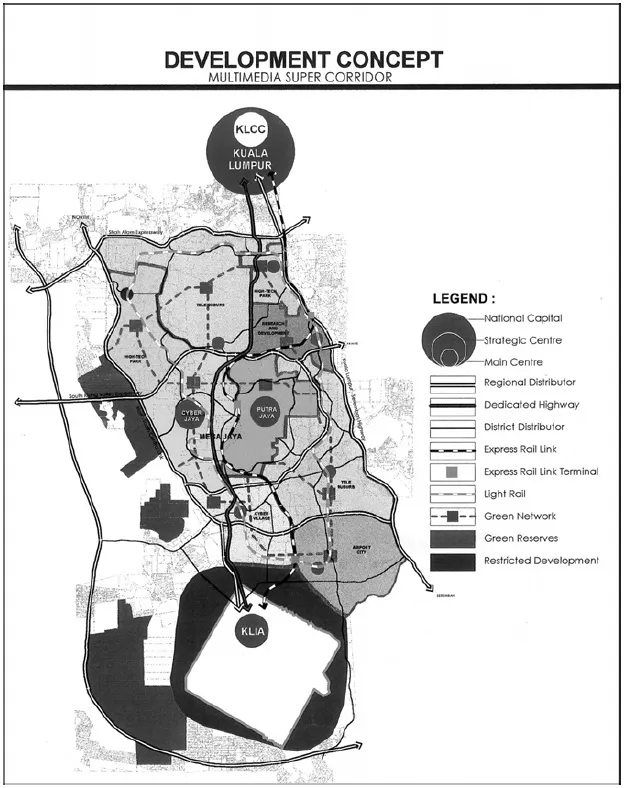

On 1 August 1996, Malaysian Prime Minister, Dato’ Sri Dr Mahathir Mohamad announced that a 50 km corridor of land extending southwards from the federal capital, Kuala Lumpur, had been designated as a special zone for the development of information and multimedia technology (Mahathir, 1996a). The Multimedia Super Corridor (MSC) gave a high-tech urgency and apparent coherence to existing processes of social and spatial development in Malaysia’s main metropolitan region. MSC was delimited by two existing high-profile megaprojects. At the northern end was Kuala Lumpur City Centre (KLCC), a ‘city-within-a-city’ commercial development which included the world’s tallest building, the Petronas Twin Towers. At the other end, MSC’s southern-most point was Kuala Lumpur International Airport (KLIA) which eventually opened in 1998. In between these poles, work was under way on a new 4,581 hectare federal government administrative centre known as Putrajaya (see Figure 1.1). At the launch of MSC, Mahathir announced that Putrajaya would be accompanied by an ‘intelligent city’ for high-tech companies. Cyberjaya, as this became known, and Putrajaya were to be connected up to either end of the new urban corridor. This book provides a critical geographical analysis of the intelligent landscapes of the Multimedia Super Corridor, a project that Mahathir proudly announced as a ‘world first’ (Mahathir, 1996a).

For all its supposed uniqueness, the MSC project was one of a succession of attempts around the world to create a Silicon Valley-style ‘technopole’ (see Castells and Hall, 1994; Winner, 1992). Wired magazine identified and evaluated some forty-six would-be ‘venture capitals’ in mid-2000 (Hillner, 2000). These otherwise diverse locales share two key characteristics. First, is the attempt to attract and foster innovative economic activity. They seek to become ‘hubs’ for regional operations of existing leading-edge high-tech companies and breeding grounds for new ones. Second, is a logic of connectivity, a perceived necessity of ‘plugging in’ to a global ‘space of flows’ (see Castells, 1996). MSC was built upon a 2.5—10-gigabit digital optical fibre backbone enabling direct high-capacity links to Japan, the USA and Europe (Multimedia Development Corporation, 1996a). The particular vogue for innovative and wired urban spaces in the Asian region in the

Figure 1.1 Development Concept: Multimedia Super Corridor.

Source: Reproduced with permission from Multimedia Development Corporation.

Source: Reproduced with permission from Multimedia Development Corporation.

mid-1990s led two commentators to refer to a generalised ‘Siliconisation of Asia’ (Jessop and Sum, 2000).

Malaysia’s high-profile Siliconisation in and through MSC drew upon celebratory accounts of a supposedly new era based on information and communications technology (see, for example, Gates, 1995). Political speeches, marketing brochures and exhibitions presented an information society which would not only be more affluent, but also variously simpler, cleaner, more environmentally-friendly, more efficient and more egalitarian. The ability to overcome constraints of space and time, a familiar theme in utopian imaginings of technological change, was projected in domains ranging from health care provision (through ‘telemedicine’) to public sector services (using ‘electronic government’). Specifically electronic promises were articulated in new vocabularies of technological optimism speaking, for example, of ‘smart schools’ and a variety of ‘intelligent features’. As ‘a global facilitator of the Information Age’ (Mahathir, 1996a), MSC would lead Malaysia to a national ‘Multimedia Utopia’ (Multimedia Development Corporation, 1997a: 4).

Despite this utopianism, the very ideal of connecting up to an Information Age whose imagined centre lay elsewhere appeared to reaffirm Malaysia’s global peripherality. Technological utopian futures were, of course, premised on advancing from a not-so-idealised present. More than this, any contemporary technological lack was to be addressed in MSC by importing ‘progress’. The state-controlled Malaysian press in 1997 charted the number of companies applying for ‘MSC status’, celebrating each ‘world class’ foreign addition as a step closer to the indigenous nurturing of innovative and creative selves — what have been referred to elsewhere as ‘Homo Silicon Valleycus’ (Thrift, 2000a: 688). Some of this breed sat on MSC’s International Advisory Panel, legitimising the corridor and steering it towards its ‘intelligent’ evolutionary apex.1 The centre of older ‘biological geographies’ (see Rose, 1999: 38) had thus shifted from Western Europe to Southern California. Yet the locus of an imagined Silicon modernity of global flows and connectivity remained very much ‘out West’.

In this book, I argue that MSC cannot be adequately understood as either an expression of a paradigmatic global shift to a new techno-economic era or in terms of the expansion of a modern ‘West’ into a ‘non-Western’ periphery. In the first place, it is important to reject any suggestion of a wholesale transition to a distinct new technological epoch. As Nigel Thrift (1996a) has reminded us, writing about new technology has a propensity towards notions of rupture and ‘revolutionary’ understandings of social change. More nuanced accounts attend to the messy complexity of social and political constructions of technology in particular places rather than ‘explaining’ transformation in terms of the emergence of a generalised Information Age. Second, reinscribing a generalised West—other cartographic dichotomy makes little sense in a world where social, economic and technological processes are increasingly global in scope. ‘Western’ knowledge, as Wendy Mee has argued, is always already part of Malaysia’s ‘in here’ (Mee, 2002: 70). In addition, to reduce transformation to the effects of some supposedly external, modern(ising) force is to deny the agency of in situ individuals and institutions. A critical analysis of Malaysia’s Siliconising landscapes, in other words, cannot proceed in the absence of the human geographies of ‘real’ places.

The focus of this research, then, is the people, places and landscapes of Malaysia’s Multimedia Super Corridor. This is not to deny the significance of broader advances in information and communication technologies nor connections with distant locales such as in the USA. Clearly, emergent informational economies rationalise investment in Silicon Valley-style technopoles; and the form that these take in Malaysia, as elsewhere, is shaped in part by flows of knowledge, capital and people from other(s’) places. However, I seek to combine these insights with a more grounded perspective. This means not so much seeing MSC as diagnostic of somehow more fundamental or more important processes and forces. Rather, it means attending to how ‘intelligent’ landscapes and lives in MSC are shaped by people and processes at a variety of scales. It also means considering how ostensibly ‘local’ MSC norms and forms are bound up with networks of culture and power, in reciprocal — if asymmetrical — relation to elsewhere. Such an approach demands a conceptualisation of locality which is not geographically-bounded. Work in human geography has shown how place (Massey, 1993), landscape (Schein, 1997) and the local (Mitchell, 2001) can be spatialised rather differently — in terms of an ‘articulated moment in networks that stretch across space’ (Schein, 1997: 662). Following such conceptual qualification, this work may be understood as a local study of MSC landscapes and as an analysis of the modernity of a particular place and time.

Reworking modernity

To speak of modernity in terms of spatial and temporal specificity may conventionally be considered as somewhat contradictory. ‘Modernity’ has been an occasion for the very kinds of portentous theorisation and epochal claims from which I have sought to distance the approach adopted in this book. However, recent historical work in geography has demonstrated how a consideration of ‘spaces of modernity’ sidesteps some of the pitfalls of ‘grand’ theory (Ogborn, 1998: 2; see also Nash, 2000). As Miles Ogborn has put it, situating the concept involves ‘fracturing modernity as a totality by contextualising it in terms of specific histories and geographies’ (Ogborn, 1998: 38). Modernity, in this way, is not claimed as a generalised new period or stage, but as a way of framing specific transformation; it is less an attempt to formulate universally-applicable explanation, than a perspective for the study of particular geo-historical spaces.

There are three further geographical dimensions to the critical reworking of modernity in this book. The first, and most straightforward, is the study of modernity beyond the metropolitan centres of ‘the West’. As Nash and Graham (2000: 2) have pointed out, ‘While there is increasingly sensitivity to social relations based on gender, race and class, less attention has been paid to the different historical geographies of modernity beyond the metropolis, in the margins of Europe or in the non-European world’. I consider the modernity of the high-tech spaces of 1990s Malaysia. This implies more than just a remapping of modernity into territories of the ‘non-European world’. Rather — and this is the second geographical dimension — I am concerned with the active role of space in the realisation of new cultural-economic processes and practices. MSC landscapes are considered to form part of attempts to foster new ways of being and seeing. Modernity here, in other words, is understood as experienced through rather than merely in space. This, in turn, leads on to a third dimension: differentiated experiences of modernity in different times and places. It is important to clarify that I am not positing the existence of bounded, alternative (or ‘non-Western’) modernities. Rather, I argue, a multiplicity of experienced modernities is forged through shifting networked relations of interconnection which resist bounded topological packaging — and which therefore unsettle the very binary of West—the rest.

The plurality implied by taking seriously geographical as well as historical specificity might appear better suited to the frame of ‘postmodernity’ than to the perspective or stage that this is implied to have moved beyond (see Harvey, 1989). For Joel S. Kahn (1998: 83), however, a combination of accelerated capitalist transformation, rapid bureaucratic rationalisation and political commitment to discourses of modernisation in Malaysia in the 1990s signalled a ‘reworking of the modern project’ that was more accurately labelled ‘neo-’ than ‘postmodern’. On the one hand, Malaysia was politically committed to joining the ‘fully developed’ ranks of mostly Western countries (Mahathir, 1993). On the other hand, there were national- and regional-scale reasons for political reworking of Euro-American-centred meanings of ‘development’ and ‘modernisation’. Economic depression in the mid-1980s had been followed by a period of unprecedented growth in Malaysia.2 Not only did this appear to vindicate Mahathir’s economic policies; it also dampened opposition to the increased authoritarianism which accompanied his administration in the late 1980s. The year 1995 saw an electoral landslide for the ruling Barisan Nasional (‘National Front’) coalition (Liak, 1996). This represented a personal triumph for Mahathir who, like the country as a whole, appeared finally to have emerged from a period of political insecurity and uncertainty (Harper, 1996). A series of monumental state development projects, including the MSC, were founded not only on this new stable personal and national ground, but also on a regional belief that history and geography themselves were on Malaysia’s side. The twenty-first century, after all, would be the ‘Asian Century’ (New Perspectives Quarterly, 1997).

The economic performance of Asian ‘tigers’ and ‘dragons’ emboldened regional elites to make truth claims about the leading edge of global change in the 1990s. Stories of (East) Asian ‘miracles’ (World Bank, 1993) fuelled re-imagination of the mystical, sleepy (post-)colonial Orient as, at once, a new threat to Euro-American supremacy and a new paradise of economic opportunity (see Dirlik, 1998). Thus, while there was some critique of the human rights and environmental records of rapidly-developing Asian economies (Seabrook, 1996), there was also no shortage of ‘pilgrims’ eager to learn the ‘Asian way’ (Webb, 1996). One of the most vociferous advocates of ‘Asian values’, Prime Minister Mahathir was a key actor in the discursive as well as material construction of an ordered and disciplined ‘East’ in opposition to a ‘West’ imagined as decadent and decaying (Mahathir, 1996b; see also Mahathir and Ishihara, 1995). Rather than the post-Soviet Union ‘end of history’ (Fukuyama, 1992) and a liberal democratic ‘capture’ of modernity for itself (Held, 1992), Asian values or ‘Renaissance’ (Anwar, 1996) implied the return of history and the possibility of alternative modernities. Imaginatively and cartographically realigned as part of a ‘new Asia’ (Noordin, 1996: 6), Malaysia and other countries in the region could now plot courses to their own (neo-)modern futures.

This is not to suggest that modernity’s multiplicity is either reducible to elite discursive reworking or specifically territorialised at the national scale. First, Asian values and other discourses associated with political elite groups merely form part of broader shifting constellations of political and cultural forces (Kahn, 1997). There is clearly a connection between political discourse and practices of the ‘national self’ through processes of ‘cultural subjectification’ (Holden, cited in Wee, 2002: 19). In this book, I give attention to the ‘cultural’ dimensions of (self-)regulation and seek to contribute to recent work subjecting discursive practices to post-structuralist theoretical scrutiny (see Yao, 2001a: 3). Yet it is also important to consider that elite discourses themselves emerge from the ongoing reworking of ‘development’. A range of political and cultural authorities including — but certainly not only — state actors contest appropriate aims of and means to social transformation, including the role of the state. Aihwa Ong’s recent work is instructive here in giving attention to specific ‘modes of biopolitical regimes’, particular relations of state, culture and capitalism in Southeast Asia (Ong, 1999: 35). If modern ‘bio-power’ is oriented to the enhancement of the lives and welfare of national populations (Foucault, 1990: 143), Ong considers particular forms and mixes of political (non-)intervention in the government of populations and relations with global capital (Ong, 1999). In this way, it is possible to situate elite discourses in broader governmental rationalities — appropriate aims of and means to development — in particular times and places.

However, second, the diversity of bio-political regimes defies simple mapping onto nation-state boundaries. It is increasingly possible to identify differentiated spaces or zones of bio-political regimes within and across national boundaries, thus fragmenting the nation-state as a coherent ‘territory of government’ (Rose, 1996a). Aihwa Ong (1999: 21) elaborates this process in relation to the emergence of what she terms the ‘postdevelopmental state’: people and places within national territories are subjected to variegated degrees of state and corporate regulation as well as to different modes of state power. The effect of postdevelopmental strategies may therefore be to foment new patterns of exclusion and inequality — there is clearly nothing inherently celebratory about the reworking of modernity beyond ‘the West’. In addition, as we will see, political tensions arise from post-developmental disjunctures between ostensibly national development and bio-politically privileged trans- and sub-national spaces.

These issues motivate a critical geographical engagement with the development of the Multimedia Super Corridor. Work in anthropology, urban planning and geography has already yielded some social scientific analysis of the MSC project (Hutnyk, 1999; Mee, 2002; Boey, 2002; Bunnell, 2002a and 2002b). However, existing book-length treatments have been at best descriptive and/or prescriptive if not explicitly promotional (Ibrahim and Goh, 1998; Norsaidatual et al., 1999). One, carrying dual subtitles of ‘what the MSC is all about’ and ‘how it benefits Malaysians and the rest of the world’ lauds MSC as an ‘engine of growth for Malaysia’s Information Technology (IT) industry’ and even provides details of how companies can apply for ‘MSC status’ (Ibrahim and Goh, 1998: 130). In Malaysia, Modernity and the Multimedia Super Corridor I do not so much contest boosterist texts, as seek to incorporate them in diagnosing prevailing rationalities of development. I do not attempt to evaluate MSC in its own terms — to draw up, for example, a balance-sheet of its planned versus actual completion schedules, investment targets or innovation achievements — nor do I explicitly propose an alternative ‘way forward’. My aim is to provide a critical examination of both the processes and systems of evaluation which underlie the emergence of MSC landscapes and their socio-spatial outcomes.

Landscape is a key concept in this critical cultural geography of MSC, denoting both material space and governmental strategies to induce new ways of seeing and being. On the one hand, MSC is a roughly 50 by 15 km site with new urban forms and intelligent infrastructure to facilitate new forms of living and working. On the other hand, MSC landscapes in various media make known ideals of conduct for the (self-)realisation of suitably high-tech subject-citizens. Particularly during the main period of fieldwork in 1997 upon which this book is based, the sights of MSC — in brochures, advertisements and public exhibitions — visualised ideals of individual and national conduct. MSC’s intelligent landscaping, then, may be understood normatively rather than in purely technological or infrastructural terms. Both within and beyond the corridor, individuals and groups varied — and continue to vary — in their ability (and willingness) to realise themselves in ‘intelligent’ ways. If a reworking of modernity is understood in terms of the constitutive extra-local connections of MSC landscapes, therefore, this critical geography also brings into view emergent social and spatial dividing practices at a variety of scales.

The structure of the book

The book is divided into two parts. Part I provides an extended theoretical and geo-historical framing of the Multimedia Super Corridor. ‘Framing Malaysia: concepts and context’ consists of two chapters. Chapter 2 considers how the concept of modernity in social science has been taken to refer to — and has, in turn, constructed — a spatial and temporal division between the modern and its ‘others’. I show how modernity can be productively applied to analyses beyond ‘the West’ without reinscribing a geographical opposition of Western and ‘other’ modernities. Drawing u...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dediacation

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgements

- List of Abbreviations

- 1 Introduction

- Part I Framing Malaysia: Concepts and context

- Part II On Route 2020

- Notes

- Reference

- Index