eBook - ePub

Home Treatment for Acute Mental Disorders

An Alternative to Hospitalization

- 328 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In the U.S., when a patient is in need of rigorous psychiatric care, the first step is hospitalization. However, elsewhere in the world, psychiatric home treatment is proposed as an alternative. Model programs in Canada and the United Kingdom are publicly administered by community health agencies or teaching hospitals. Home Treatment for Acute Mental Disorders provides a review of the literature on home care and describes working programs around the world. This timely volume reviews treatment plans for different disorders with case illustrations, explains the administration of a PHC program and offers guidelines to case workers. It will be of interest to psychiatrists and policy makers working on the issue of patient hospitalization.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Home Treatment for Acute Mental Disorders by David S. Heath in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Psychiatry & Mental Health. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One

Review of Research on Mobile Crisis Home Treatment

ªIn view of the consistently positive findings for this type of treatment, it is difficult to know why it has not been more universally adopted.º

(Dean & Gadd, 1990)

ªCommunity care alternatives are capable of reducing the need for inpatient treatment. The trouble is that we don't know to what degree. Current scientific knowledge is not sufficient to base a radical reduction of beds on.º

(Kluiter, 1997)

Those with clinical experience of MCHT, who have seen admission to hospital averted many times, even for very sick individuals, and have witnessed the relief on the faces of the patients and their families, will share Dean and Gadd’s enthusiasm and puzzlement. However, donning one’s mental health services researcher hat, or one’s mental health systems planner’s hat, one has to agree with Kluiter; caution is required in adopting this model of care. All of the comparative studies are flawed to some degree; for example, questions have been raised about the degree to which their findings can be generalized to the general clinical population we deal with today, and we are often left in the dark regarding the conventional hospital-oriented treatment to which MCHT is compared.

The irony is that while we mull over these studies, and wrestle with whether MCHT can be an alternative to admission, we lose sight of the fact that what MCHT purports to replace—hospital treatment—has, itself, been poorly evaluated (Kluiter, 1997).

More and different kinds of research are clearly needed; in spite of this, however, critical reviewers have all come to positive conclusions in some

SIDEBAR

Common Flaws in Mobile Crisis Home Treatment Research

- Poorly defined target population: although severely mentally ill, it’s unclear if they were in crisis and in need of immediate hospitalization

- Little information provided regarding the numbers and characteristics of patients excluded or dropped out

- Exclusions such as high suicide risk, or living alone, limit the generalizability to the average in-patient population

- Especially in older studies, the patients may be less ill than current patients admitted to hospital

- Control hospital-based services poorly described—it is hard to know what the experimental group is being compared to

- The control group treatment is far removed from today’s superior conventional community-based out-patient treatment—so the comparison is not as relevant to today

- Family burden not measured

- The experimental treatment group is not a pure replacement of just hospital care; most of them engage in some form of crisis intervention (Stage 3) or psychiatric emergency evaluation (Stage 4), and many of them continue their involvement with the patient into the follow-up or out-patient phase (Stage 6 in the anatomy of a crisis diagram). See Figure 1.1

- There are limits to the general application of experimental programs because they employ special start up funds, enjoy the nonspecific “Hawthorne effects” of being part of an experiment, and benefit from the contributions of charismatic individuals. (Thornicroft & Bebbington, 1989)

- Meta-analytic reviews may include research from countries with different health care infrastructures; the question of how well mental health care models travel is highly relevant

measure. Braun, et al. (1981) state “A qualified affirmative response to the question of the feasibility of deinstitutionalization can be given with regard to programs of community care that are alternatives to hospital admission… “Kluiter (1997) concludes that “community care arrangements are capable of reducing the need for in-patient treatment. The trouble is that we don’t know to what degree.” Joy, Adams, and Rice (2001) state “Overall, the review suggests that home care crisis treatment, coupled with an ongoing home care package, is a viable and acceptable way of treating people with serious mental illness….” Burns, et al. (2001) declare “Our finding that in-patient control studies found a difference of nearly five days in hospital per patient per month in favor of home treatment (at one year) was open to question due to the difficulties of metaanalysis…. Nevertheless, if this finding is valid, it’s magnitude is extremely significant clinically. Home treatment services achieved fewer days in hospital than services involving at least an initial period of in-patient treatment (in-patient control studies). We recommend that studies of home treatment compared with admission are no longer initiated, at least where hospitalization is used as an outcome measure.”

Mobile Crisis Home Treatment (MCHT) has been the subject of at least 14 comparative studies, in five countries (and four continents), all but one of which have found it to reduce bed usage, to be less expensive, equally effective, and preferable to inpatient care.

Eight studies are randomized controlled trials in which patients presenting in an emergency are treated by MCHT or admitted to hospital; in three studies in one catchment area MCHT is compared to a conventional service (usually hospital based with traditional out-patient services) in a similar catchment area; and in three studies, there is a comparison of two different time periods in the same area: before and after the establishment of the MCHT service. All reported differences are statistically significant.

In each decade from the 1950s to the 2000s, research studies have shown MCHT to be less expensive, equally effective, and in some ways preferable to the contemporaneous hospital services. In the older studies, the hospital practices that are contrasted with MCHT are outdated; however, these studies are included in the review for two reasons. One is to show the historical evolution of this model, and, in particular, the consistent practical lessons that recur in each study —useful for understanding the key elements and principles described in Chapter 4. The other is the fact that some of these older studies were among the five that were of sufficient quality to be included in the 2001 Cochrane Library review of this model (Joy, Adams, & Rice, 2001). These five studies are Pasamanick, Scarpitti, and Dinitz (1967); Stein and Test (1978); Fenton, Tessier, and Struening (1982); Hoult and Reynolds (1984); and Muijen, Marks, Connolly, and Audini (1992).

COMPARATIVE STUDIES OF MOBILE CRISIS HOME TREATMENT

The Worthing Study: A Comparison of Two Time Periods, Before and After, 1958 (Carse, Panton, & Watt, 1958)

This, the first study of mobile crisis home treatment took place 40 years ago in the southeast of England in two towns, Worthing and Chichester. The

Table 1.1

area, predominantly wealthy, high social class, with many retired persons, sounds an unlikely location to have a psychiatric bed shortage so severe as to force such an innovative approach. But that was the motivation: too many patients for too few beds. Then, as now, access to in-patient treatment had become limited. Admissions to mental hospitals in the U.K. had increased by 40% in five years in the 1950s, and the number of psychiatric beds peaked in 1954; but, there was a serious overcrowding problem. The only answer seemed to be to build more hospitals—until the regional hospital board decided to undertake a twoyear pilot project to provide a mobile crisis home treatment service (termed “outpatient and domiciliary treatment service”) to patients in the Worthing district, starting January 1, 1957. This district was deliberately chosen because it was 22 miles from the nearest mental hospital, Graylingwell, to show that it is possible to provide psychiatric treatment for large numbers of patients without the immediate availability of a modern mental hospital. It became known as the “Worthing Experiment.”

10-Month Period

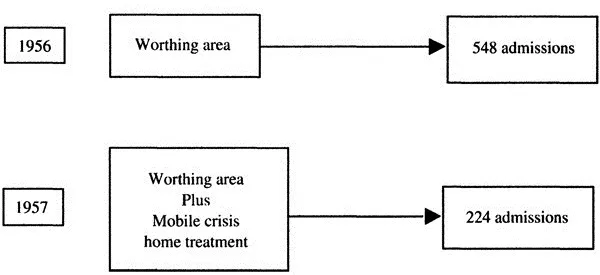

Figure 1.1 Worthing study.

All patients had to be referred by their primary care physician, and the service functioned as the only gatekeeper to the mental hospital. The area had a wide range of social classes, and, of particular interest, the highest proportions of elderly people of any town in Britain; how far it is possible to treat elderly psychiatric patients out of hospital was of urgent concern. Staff consisted of two and a half psychiatrists, at least four nurses, two orderlies, two social workers, and an occupational therapist.

Admissions to Graylingwell for the first ten months of the new service in 1957 were compared to those in the same months in 1956. The results were dramatic: 60% reduction in admissions from Worthing (from 548 to 224), compared to a 4% increase in admissions from other districts (Figure 1.1). The study is short on details; diagnoses are not described with the rigor and detail of today, clinical outcomes are not compared, and it is hard to compare the acuity of the patients with today’s patients. Also, the program provided more community services in general beyond home treatment, making it difficult to separate out the specific role of home treatment in this result. Finally, there was no attempt to measure family burden.

The Worthing patients were mainly suffering from depression. ECT was used extensively, and modified insulin treatments were given. The main treatment was individual psychotherapy.

The Chichester Study: A Comparison of Two Areas, 1966 (Grad & Sainsbury, 1966)

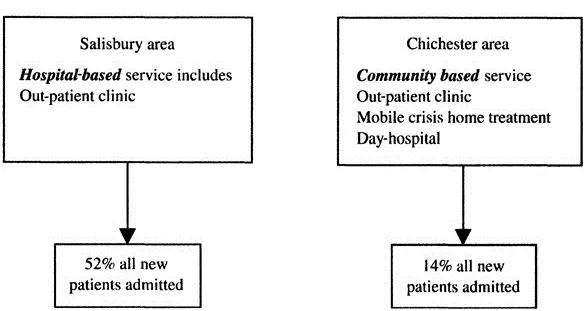

A year later, Grad and Sainsbury (1966) replicated the Worthing Experiment in Chichester for the same reason: overcrowded mental hospitals. They compared two districts: Chichester, where community services were set up, including mobile crisis home treatment and a day hospital; and Salisbury, which had a hospital-centered service. The two areas were similar with respect to psychiatric population referred, except that the Chichester service received more elderly patients and organic disorders and fewer neurotics. Any bias, therefore, is toward more severe cases in Chichester.

Again, the results were dramatic: 14% of patients referred to the Chichester service were admitted to hospital, compared to 52% referred to Salisbury; 15% were treated in a day hospital and 16% treated at home, compared to 3% at home in Salisbury; and none in a day hospital (Salisbury, as in the rest of the U.K., already had an existing form of home treatment, but less extensive than the new service).

Such little consideration of community treatment appears to have been the norm in this era that in retrospect it would appear to have been comparatively easy to bring about such dramatic reductions in admissions. For

Table 1.2

Figure 1.2 Chichester study.

Two-Year Follow-Up

Table 1.3

example, many patients came into the mental hospital directly from their primary care physician, “this could occur without the hospital being aware that it was getting a new patient.”

Family burden was measured, the overall result being no significant difference between the two services after one month (Grad & Sainsbury, 1968). However, there was a tendency for the hospital service to provide more relief in the less severe cases by way of more social work support to families, underscoring the need to provide more attention to families in home treatment.

Table 1.4

The Louisville Kentucky Study: A Randomized Controlled Trial, 1967 (Pasamanick, Scarpitti, & Dinitz, 1967)

A few years later, across the Atlantic, in Louisville, Kentucky, in the first American study of MCHT, Pasamanick, et al. (1967) focused on a different population of patients for home treatment: patients with schizophrenia. For the first time, the new neuroleptic drugs had opened up the possibility of treating these patients in the community instead of in the hospital. At that time, patients with schizophrenia were staying in hospital an average of 11 years, and, except for the drugs, were receiving only custodial treatment. Concern over this grim state of affairs seems to have been the driving force behind this landmark study.

The study was designed to determine:

- whether home care for patients with schizophrenia was feasible.

- whether drug therapy was effective in preventing their hospitalization.

- whether home care was, in fact, a better or poorer method of treatment than hospitalization.

Viewing this study as a hospital vs. home care experiment, from the vantage point of today, is complicated by the incorporation of a drug vs. placebo experiment and by the fact that hospital care today bears little resemblance to hospital care at the time of the study. As described in the study, “In the hospital, between acute episodes, patients are mostly left alone to stare vacantly into space, to walk down the corridors and back again, to sit, rock and hallucinate, or to partake of inmate culture. In time, this lack of normal stimulation— intellectual, interpersonal, even physical—has usually resulted in deterioration and impairment of functioning which was wholly unnecessary.”

The study compared 152 patients admitted over 25 months of intake, and followed for 6–12 months. They were assigned randomly to three groups:

- Home on drugs

- Home on placebo

- Hospital

To qualify for home care, patients were required to:

- Have schizophrenia, with psychosis severe enough to warrant hospital admission

- Display no homicidal or suicidal tendencies

- Fit within the age range of 18–60

- Have family or family surrogate willing to accept and supervise them in the home and to report on their progress throughout the course of the study

- Reside within 60 miles of Louisville

No criteria for diagnosing schizophrenia are given, and today the concept of this illness is much narrower. From the case descriptions, these patients certainly appeared psychotic, and would have warranted hospital admission; however, many of them wo...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Acknowledgments

- Foreword

- Preface

- Introduction

- Chapter One Review of Research on Mobile Crisis Home Treatment

- Chapter Two Why Mobile Crisis Home Treatment? How Does it Fit with Mental Health Systems?

- Chapter Three Descriptions of Seven Mobile Crisis Home Treatment Teams

- Chapter Four Key Elements and Principles of Mobile Crisis Home Treatment

- Chapter Five How to Set Up and Operate a Mobile Crisis Home Treatment Service

- Chapter Six Daily Program Operation

- Chapter Seven Mobile Crisis Home Treatment of Mental Disorders: Part I

- Chapter Eight Mobile Crisis Home Treatment of Mental Disorders: Part II

- Appendix

- Bibliography