- 296 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This anniversary study presents a readable, informative account of the development and current structure of Berlin.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Berlin by Dorothy Elkins,T. H. Elkins,B. Hofmeister in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Sciences physiques & Géographie. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Sciences physiquesSubtopic

Géographie1

Berlin: product and victim of history

1.1

The rise to capital status

1.1.1

No outstanding natural advantages

At the heart of modern Berlin, the dark, polluted waters of the river Spree slide malodorously round the island of Cölln, that once contained the Berlin Palace of the rulers of Prussia and of the German Second Reich, now replaced by the glass-fronted modernity of the Palast der Republik of the GDR, a building that houses the country’s parliament (see figs 6.1 and 6.2). Here, where the stream once divided into three branches and was further interrupted by sandbanks, was from the earliest times the lowest easy crossing of the Spree before it emptied into the wider and often lake-like Havel river. It lay at a point where the low glacial-drift plateaus of Barnim to the north and of Teltow to the south, zones of relatively easy movement by land, were less than 5 km apart across the course of the Berlin Urstromtal (former proglacial melt-water channel) within which the river flows. In this part of its course the Spree is clear of the lakes which clutter the Havel confluence in the neighbourhood of Spandau to the west and the Dahme confluence in the neighbourhood of Köpenick to the east, lakes which were later to become a precious recreational resource for the future world city (see fig. 3.1 ). It must not be forgotten that the Spree, as well as being an obstacle to be overcome, was also a means of movement by water, as it remains to this day. When frozen in winter it could also be used for movement by sledge (Cornish 1923:153–5).

If the geographical situation of Berlin had some advantages, its site was not particularly suitable for building purposes. The sands which form the floor of the Urstromtal are intermixed with peat, forming a particularly treacherous foundation. The earliest nuclei, from which medieval Berlin coalesced, clung to sandbanks, still marked today by the city’s surviving medieval churches, such as the Marienkirche, which now shares its ‘island’ with the East Berlin TV tower. Problems with the foundations of buildings have continued throughout the city’s history.

Cölln, on its island, was one of the numerous towns founded in the course of the German eastern colonization. The year 1237, when it was first recorded, is conventionally accepted as the date of the foundation of the whole city. Its twin town of Berlin, on the north bank, was first recorded in 1244, but archaeological evidence suggests a Germanic occupation of both Cölln and Berlin at least eighty years earlier than indicated in documentary sources, perhaps in the decade 1160– 70. Unlike some other German town sites in the region, Berlin-Cölln does not appear to have been preceded during the Slav period by any significant settlement.

The advantages of the Spree crossing were not overwhelming, even in the medieval period. Within the area of what was to become Greater Berlin there were two earlier sites of urban or proto-urban nature. To the west, Spandau was a fortified Slav settlement dating from the end of the eighth or the beginning of the ninth century AD, commanding the Spree-Havel confluence. Similarly, the Slav settlement of Köpenick to the east commanded the Dahme-Spree confluence (see section 6.4.4.). Between the two, Berlin had no particular prominence among the German towns that were established between the Elbe and Oder rivers, and lay away from the major medieval trade routes. What can perhaps be said is that as soon as the plateaus of Teltow and Barnim became the scene of organized German village settlement, their easy accessibility enabled Berlin-Cölln to organize a coherent local market area, whereas Spandau and Köpenick were hemmed in by the lakes which, at an earlier stage, had been a defensive advantage. It was also possible at Berlin to dam one of the branches of the river to power a public mill, still recorded in the street name Mühlendamm. Nevertheless, towns a little further afield, such as Magdeburg or Frankfurt on Oder, were certainly better endowed by nature than Berlin-Cölln. We must look to other causes than the natural environment for a sufficient explanation of the rise of the city to world status.

1.1.2

Berlin’s geographical situation

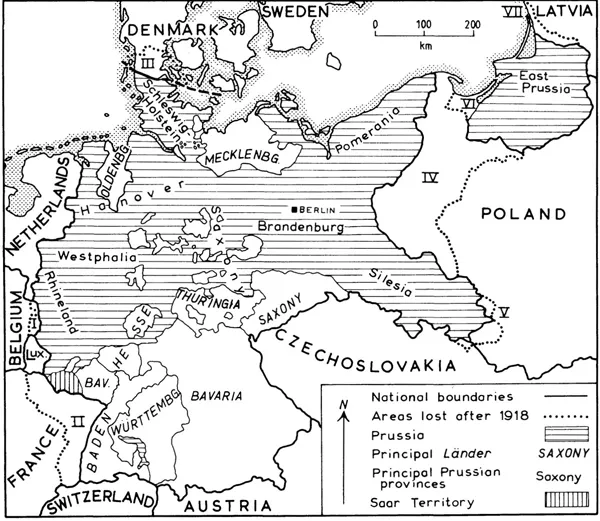

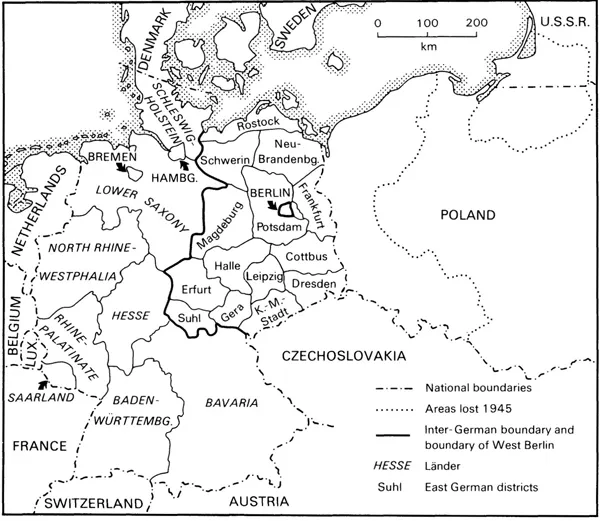

The advantage to a capital of having a central situation within the territory of a state can, perhaps, be overstressed; it is not difficult to compile a list of capitals that have apparently managed to function quite adequately from markedly asymmetrical positions. Certainly, Berlin has rarely been centrally placed with regard to the fluctuating expanses of German territory that the city has from time to time controlled. Even within the Germany of the Second Reich of 1871, Berlin was not far off 100 km closer as the crow flies to its furthest north-eastern outpost at Memel (now Klaipeda in the Soviet Union) on the Baltic than to its south-western extremity in Alsace, although on the other diagonal the cities of industrial Upper Silesia and the Danish frontier were approximately equidistant. The biggest disparity was on Berlin’s own latitude, where the boundary with Russian Poland to the east was about 280 km distant, whereas the Netherlands frontier in the other direction was over 400 km away (fig. 1.1). The asymmetrical location of Berlin has been accentuated by the results of two world wars: whereas the Netherlands boundary has scarcely changed, the boundary with the territory occupied by Poland as a result of the Second World War lies less than 80 km distant in the direct line. By autobahn to the official crossing point it is about 100 km, a little further, but still only about an hour and a half s journey even at the sober pace of GDR road traffic (fig. 1.2). Within the reduced area of the German Democratic Republic, Berlin is much more centrally placed than within the pre-1914 Reich; nevertheless, the southern crossing into Bavaria is some 275 autobahn km away (at present five hours or more by train) as compared with the proximity of the boundary with Polish territory to the east.

Figure 1.1 Political divisions after the First World War

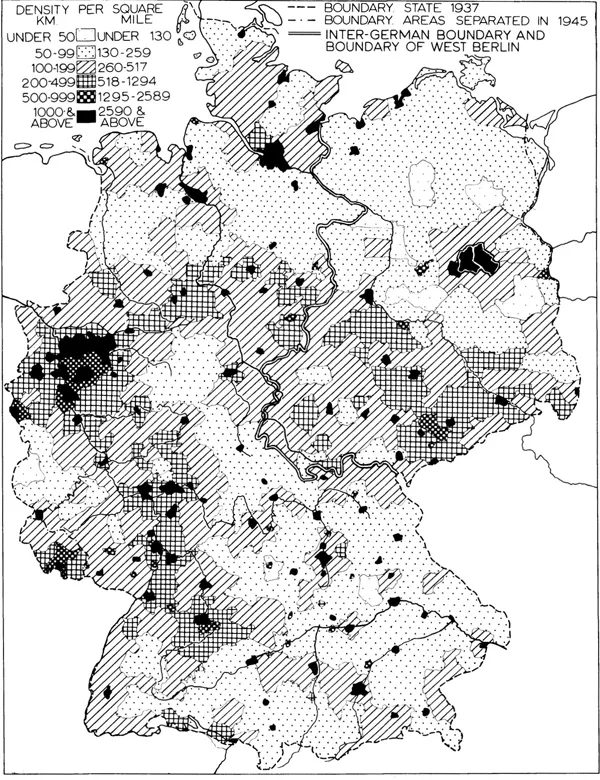

It is more meaningful to relate the geographical situation of Berlin not to distance in an absolute sense but to the distribution of population, which can broadly be taken as an indicator of the distribution of economic activity and economic opportunity. Central Europe has two major axes of population and urban density. One follows the Rhine from Switzerland to its mouth, the second intersects the first in the Ruhr area and runs somewhat south of east through Hanover to Saxony and Silesia (fig. 1.3). It might be expected that an ideal German capital would be located somewhere on these axes, preferably at their intersection, whereas Berlin is situated in their north-east quadrant, in the relative emptiness of the North German Lowland. Within this general area it has not even the advantage of a situation on the Baltic coast. What can perhaps be said is that in the narrower context of the GDR the location of Berlin on the Northern Lowland provides a valuable spatial counterweight to the cities of industrial Saxony, contributing towards meeting the country’s spatial-planning goal of balanced regional development.

Figure 1.2 Political divisions after the Second World War

Berlin’s relative isolation from other major centres of population and economic activity is however mitigated by the lack of natural obstacles in the terrain that surrounds it; once the city began to develop in importance, it was able to establish the necessary external linkages without insuperable difficulty. Although Berlin was a member of the Hanse at the latest by 1359 (Vogel 1966), it was not on any of the really major routes running southwards from the coast, and it lay north of the great east-west routes along the Harz Foreland and through Thuringia. Yet once Berlin began to assume importance as a residence of the rulers of Brandenburg, there was no difficulty in diverting the post roads through the city and the adjoining palace town of Potsdam. Similarly, there was no obstacle to making Berlin the heart of the nineteenth-century Prussian rail system, and the point of origin of the national autobahn system in the 1930s. Only with waterways has nature played a more positive role; the combination of shallow, generally east-west trending Urstromtäler, north-south breakthrough stretches (such as those occupied by the Havel) and a profusion of lakes facilitated a steady improvement of river navigation and the building of canals from the eighteenth century onwards.

Figure 1.3 The distribution of population, c.1950.

1.1.3

The product of history

It is impossible to dissociate the rise of Berlin from the rise of Brandenburg- Prussia to hegemony in Germany. Initially, the dual settlement of Berlin-Cölln was only one component in the totality of colonization measures initiated in what became the Mark of Branden-burg, designed to increase the power, the lands, and the tax revenues of the ruling Askanier family. Although the Askanier retained a residence in Berlin, the town was not one of the bastions of their power, unlike the fortress at Spandau. Berlin-Cölln was essentially a central market settlement for the planned villages of Barnim and Teltow, into which were concentrated both colonizing Germans and the indigenous Slavs, who had formerly lived in small, scattered settlements. Some of the earliest German villages appear to have originated at the turn of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries under the protection of the Knights Templar (hence the place-name Tempelhof), whose patroness was the Virgin; their villages Mariendorf and Marienfelde (among others) are part of Greater Berlin today. A mint had also been established by 1280, the most important in the Mark of Brandenburg.

The lords of the Mark were also prepared to confer a range of taxation and trading privileges, mostly, no doubt, in return for hard cash. For example, merchants passing through the town were obliged to offer their goods for sale or pay disproportionately high customs dues. It also appears that Berlin merchants were not obliged to pay customs dues to the Margrave on goods moving within the Mark of Brandenburg (Vogel 1966). The citizens grew wealthy, trading rye and timber with the ports of the North Sea coast, although social contrasts opened up between a ruling group of rich merchants and the lesser traders and craftsmen, organized in guilds.

The death of the last Askanier Margrave in 1319 ushered in a period when the Mark of Brandenburg passed through the hands of a variety of frequently absent rulers; this was also a period when Germany as a whole was in a period of political disintegration. Like other towns throughout Germany, Berlin was able to use this period of confusion to bid for increased influence and self-government. Considerable land holdings were built up in the surrounding villages, and further taxation and legal privileges were bought from the various rulers. Berlin and Cölln increased their links, especially for defensive purposes, building a third town hall for common purposes on the bridge that linked them together. Berlin became a leading member of a league of towns of the central Mark, as well as a member of the Hanse.

Independence was, however, not to last, yet ironically its loss was to ensure that Berlin would rise to be a great capital rather than fall into the political impotence of former great medieval free cities such as Augsburg. In 1411 the emperor appointed Burgrave Frederick VI of Nuremberg, a member of the House of Hohenzollern, to be governor of the Mark of Brandenburg; in 1415 he was definitively installed as Elector Frederick I.

The burghers of Berlin attempted to maintain their independence, looking for help to the Hanse, to the link with Cölln and to association with neighbouring towns in the Mark, but it was soon clear that a new era of direct princely rule had begun. The next elector, Frederick II (Irontooth), systematically eroded the privileges of the town, in part by playing on internal dissensions between the richer merchants and the rest of the population. The elector gained the right to receive the keys of the town on demand and to approve the burgomasters and members of the two town councils. Entry into leagues with other towns was forbidden, and the links with Cölln again dissolved. The commercial, customs, and legal privileges that had been granted to the town over the years were taken back into the increasingly absolutist hands of the ruler, who installed his judges in the former common town hall on the bridge linking the dual towns.

1.2

Electoral and royal capital

The new order was symbolized by the building between 1443 and 1451 of the Stadtschloss, the electoral town palace, on the island of Cölln. From about 1470– 80 this was continuously the seat of the electoral court, Berlin-Cölln thus entering on a new career as a Residenzstadt. Although clearly supreme in Brandenburg, of which it was now administratively an integral part, it was at this stage only one among many petty princely capitals in a politically fragmented Germany. That it was to rise above all these others was the result of the linkage of its fortunes with those of the House of Hohenzollern.

The transformation of Berlin-Cölln into a princely capital brought about a parallel transformation in the economic, social, and cultural life of the dual town. It came to be dominated by officials, who were under the legal jurisdiction of the court, not of the town, and who were exempt from the taxes and other obligations of citizenship. Initially, the Landtag (the parliament) met in the palace, which also housed the electoral Chancellery, the higher courts of justice, and the administrations for taxation, finance, and ecclesiastical affairs (Brandenburg accepted the Reformation in 1529–40, a move giving religious, economic, and political advantages to the ruler). What the new capital did not receive was Brandenburg’s university, which was instead founded in 1506 in the trading town of Frankfurt on Oder. Readers in England will be well aware that this was not the only example of university location outside the capital; perhaps the Electors were fearful of student unrest, or desired to keep an uncontrollable foreign element at a safe distance (Schinz 1964:66). The demand for goods to supply the court, its officials, and the army stimulated the growth of manufacturing. The richer merchants increasingly turned from long-distance trade to the more immediately rewarding business of meeting electoral needs for goods and credit. The number of inhabitants rose from 6,000 in 1450 to 12,000 at the end of the sixteenth century, in spite of periodic visitations of the plague.

By this time, the initial palace complex had been completed. An elaborate Renaissance wing had been added, overlooking a parade ground, and linked by a wooden gallery to the Hofkirche, the electoral church. Other necessities such as a guardhouse, stables and a prison were also provided. The situation of this complex in formerly neglected, swampy land at the north-west fringe of Cölln was to be of fundamental importance for the development of Berlin in centuries to come, determining that the western sector would be occupied by the ‘polite’ inhabitants of the city, and by the services that they required.

The subsequent history of Brandenburg was far from peaceful; there were severe reverses to come, but somehow (until the final fateful year of 1918) the Hohenzollerns always managed to survive each crisis and, usually, to emerge with increased territorial possessions. A particularly low point came in the first half of the seventeenth century. Admittedly, the acquisition in 1614 of Kleve (Cleves) and the Mark in the Rhinelands were potentially significant in terms of laying the foundations of the subsequent Rhine Province, and in 1618 Johann Sigismund united the Duchy of Prussia to the Electorate, but these events were overshadowed by the outbreak of the Thirty Years’ War. Berlin suffered less than the rural areas from the direct impact of military operations; unlike Magdeburg it was spared the horrors of being taken by storm, but instead had to endure occupation by a succession of armies. The inhabitants suffered by having troops billeted on them, by having their horses and cattle commandeered, and by having to contribute to repeated subsidies. Loss of trade, inflation, scarcity, and disease added to their problems. Late in the war, houses in the suburbs that had grown up outside the old walls were destroyed to prepare for a siege which fortunately never came. When the young Elector Frederick-William (1640–88) returned to Berlin, it was to a ruined city that had lost half its population, but in common with the other German princes he gained from the war the abolition of the vestigial control of the Empire over his absolute power.

Frederick-William is regarded as having laid the foundations of Brandenburg- Prussia, that improbable state that emerged not from geography, not from the logic of history, not from common ethnicity or the common interests of its inhabitants but which was ‘the creation of a few kings possessed by the fury of raison d’état and of the servants whom they commanded’ (Mann 1974:32–3). In the period 1658–83 Frederick-William caused the city to be surrounded by a belt of fortifications better reflecting the needs of the age of artillery than the old medieval wall (see fig. 6.2). These fortifications appear to have discouraged attack by the Swedes, allies of Louis XIV in his war of 1672–78 in the Low Countries, who invaded Brandenburg but failed in an attempt to take Spandau by storm. They were eventually defeated by Frederick-William at Fehrbellin, northwest of Berlin, in 1675, after which victory he was known as the Great Elector (his equestrian statue by Andreas Schlüter is a triumph of baroque sculpture and one of the artistic treasures of the city; it formerly stood on the Lange Brücke in front of the now destroyed Berlin Palace and now stands before the Charlottenburg Palace).

The permanent presence of a standing army caused inconvenience to the citizens, who had either to have soldiers billeted on them or pay for exemption, but military requirements stimulated the growth of manufacturing and a rapid rise of population, which reached 61,000 by 1710. Another contribution both to the economy and to...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Plates

- Figures

- Tables

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations

- Introduction

- 1: Berlin: product and victim of history

- 2: Berlin divided

- 3: The Berlin countryside

- 4: Transport developments

- 5: The Berlin economy

- 6: Urban development

- 7: Urban development and redevelopment after 1945

- 8: The Berlin population

- 9: Life after the Wall

- References

- Additional sources of information