1

IMAGES AND SOURCES

Mercenary terminology

The Classical Greek word for a soldier was stratiôtês. This was a neutral term, neither pejorative nor indicative of the type of soldier to which it referred. In order to be more specific, the Greeks named types of soldiers by the kind of equipment that they employed. The heavily armed infantrymen or hoplites (hoplitai) carried heavy arms (hopla), while lightly armed men (psiloi) were sometimes more specifically identified by their weapons: javelin-men or stone-throwers (akontistai, petroboloi), archers (toxotai), peltasts (peltastai) who carried crescent-shaped wicker shields (peltai), and unarmed men, literally naked-ones (gymnêtês), are all examples. Mercenaries were soldiers. The Greeks had no specific noun for a mercenary, nor a verb to denote doing mercenary service, nor an adjective to describe mercenary behaviour. Other languages developed words for mercenary service. The Latin word mercenarius is the root for the French term mercenaire and the English mercenary. It can refer to a soldier who serves a foreign power for remuneration independently from the state of which he is a citizen. The German word Söldner comes from the Late Latin solidarius, itself from the Latin solidus, the solid gold coin paid to the troops in the later Empire.

The Greek words most commonly used for mercenaries carried alternative meanings in different contexts and appear to have changed over time. This is something first noticed by H. W. Parke (1933: 20–1). In the works of the early Greek writers, fighter-alongside (epikouros), a helper, is the most common term used for a mercenary. Foreigner (xenos) could also refer to mercenaries by the fifth century BC, though it generically meant several things, such as ritualized guest-friend or stranger. Before the later fifth century, such foreign assistants were sometimes persuaded by a wage payment (misthos), perhaps to show their mercenary nature. As wages became more common in the Classical world, so new terms emerged to describe those who received them. Thus, by the later fifth and fourth centuries BC sources increasingly use wage-earner (misthophoros) to denote mercenary soldiers. Among the Greek historians of the Roman period, misthophoros became the standard word used of mercenaries of the Classical world. As more professionals appeared in battle in the fourth century so the terms for such soldiers changed over time, hence the shift from fighter-alongside (epikouros) to wage-earner (misthophoros). By the end of the fourth century, the amateur soldiers and not the professionals needed definition, and the formerly neutral Greek soldier (stratiôtês) meant the professional soldier as opposed to the citizen militiaman.

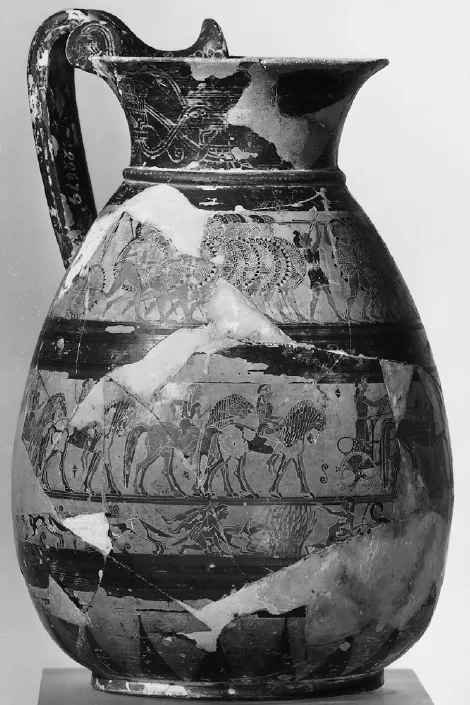

Figure 1 The seventh-century BC protocorinthian Chigi vase (olpe) has the most famous representation of hoplite warfare on the scene in its upper band. Note the large shields (aspides) and the conformity of arms (hopla) carried by the hoplites (Hirmer Verlag Munich neg. no. 591.2036).

Not all mercenaries served on land. Greek naval warfare consumed money for the remuneration of crews and oarsmen. Identifying the mercenary as opposed to the professional but citizen or allied serviceman in Classical navies is not easy, and ancient terminology does little to assist. Naval personnel required payment because they were from the poorer classes of society. The poor men (thêtes) who provided the backbone of the navies of the Classical world needed subsistence payments at the very least. The enormous numbers of men required for such service and the time involved on naval campaigns meant that naval warfare was financially consuming in a way that land warfare was not.1 Sailors (nautai), the specialist crews of triremes (hyperêsiai) and the armed marines (epibatai) received pay (misthos) from generals (stratêgoi) and ships’ captains (triêrarchoi) alike in the fifth and fourth centuries BC. Good evidence illustrates that offers of higher pay by individual ship commanders led to competition in hiring skilled and experienced seamen even from within the Athenian citizen body as early as the late fifth century (Dem. 45.85; 50.7, 15, 18; Lysias 21.10). Forensic speeches demonstrate the levels of professionalism achieved within the Athenian fleet at the time. A similar relationship existed between the poor members of a ship’s crew and their trierarch as between a mercenary soldier and his paymaster (misthodotês).

Our sources present crews as behaving in a mercenary manner. Athenian crews abandoned Athenian ships for payment, promises of higher wages, bonuses or even subsistence payments if they felt that their commander was low on resources (Dem. 50.12–16). Unsurprisingly, therefore, non-Athenian but allied crewmen from the islands in the Athenian empire, often unhelpfully called in our Athenian sources foreigners (xenoi), felt little obligation to stay with Athenian fleets in the face of higher offers of payment. Spartan, Athenian and Persian paymasters believed offers of higher pay would lure oarsmen away from their current allegiance during the Peloponnesian War (Thuc. 1.31.1, 143.1; 7.13.2; Xen. Hell. 1.5.4). Evidence shows that this was also true in the fourth century (Dem. 50). In very dire circumstances non- Athenian crewmen and slaves needed no excuse to stay with the Athenian fleet, as events at Syracuse showed to Nicias in 413 BC (Thuc. 7.13.2). Naval practices illustrate much about financial relationships and considerations of professionals in military service, but tellingly, most likely due to the financial nature of naval warfare within polis navies, no distinct terminology developed for purely mercenary as opposed to national naval crews. Naval warfare was a mercenary kind of warfare in a way that land warfare was not.

The ancient Greeks used four terms, on occasion interchangeably, for their mercenaries. These terms are central to this work. They provide a means by which men are identified as mercenaries. The terms for mercenaries changed over time and due to context. Diodorus wrote in the first century BC long after the Classical mercenary, but unconsciously identified the transformation of terminology that can be seen in the texts of his predecessors as the Greeks moved from vague terms like epikouros towards the more accurate misthophoros or the more generic stratiôtês. Diodorus came at the end of a long process of developing terminology. His unyielding preference for misthophoros over epikouros illustrates the transformation of terminology. There was a movement, unconscious though it may have been, away from euphemisms and towards more accurate terms for mercenary soldiers.

The earliest of the terms used of mercenary infantry was epikouros. Epikouros, literally fighter-alongside, might be a helper, a companion or an assistant. It was, like all the other words, not a specific term meaning a mercenary soldier. Parke (1933: 13) described it as a euphemism.2 Homer used epikouroi to refer primarily to the Lycian allies of Priam at Troy, but notably described Aphrodite as the epikouros of Ares.3 Richmond Lattimore translates this term as companion.4 Brian Lavelle interprets the epithet in Homer as positive and non-mercenary. The Lycians were good soldiers and virtuous allies (Lavelle 1997: 229–62). Archilochus (15.216; West 1993) sang unrepentantly in the seventh century that he should be called an epikouros like a Carian, though it has been questioned that he ever was a mercenary himself (Campbell 1967: 136; Lavelle 1997: 236). Lavelle thinks the poet and his audience were aware of Homer’s Lycian epikouroi. Carian was a deliberate twist from Homeric convention in the light of the recent appearance in Egypt of Carian and Ionian soldiers who found service as fighters alongside the Pharaoh in Egypt from about 664/3 BC. The impression was that they were richly rewarded for their services and so epikouros had taken on its mercenary connotations in the wake of these events. Hermippus cited a proverb in which ‘epikouroi from Arcadia’ are listed as regional imports to Athens from Arcadia (Kassel and Austin, Hermippus, frag. 63 line 18). Herodotus used this term to describe allies and auxiliaries (Hdt. 1.64.2, 154.4; 2.152.14, 163.2–3, 168.12; 3.4.2, 11.3, 11.12, 45.14, 54.6, 145.15, 146.13–19; 6.39.14; 7.189.3). The fact that he termed the Argives who fought with Pisistratus as hirelings for a wage (misthôtoi) and not epikouroi would suggest that epikouros was not a strong enough term for their relationship to the tyrant (Hdt. 1.61.4; Aristotle, Ath. Pol. 15.1–3). The sources make it clear that money lay at the centre of the Pisistratrid cause. Epikouroi continued in use through the fifth century and Thucydides used this word more than any other to describe soldiers persuaded by pay (Thuc. 1.115.4; 2.33.1, 70.3, 79.3; 3.18.1, 34.2, 73, 85.3; 4.46.2, 129.3, 130.3, 131.3; 6.55.3, 58.2; 8.25.2, 28.4, 38.3).

The term epikouros all but disappears in the histories written after the later fifth century BC. Xenophon illustrates this disappearance particularly for the first half of the fourth century BC. He used epikouros-related words only twice in the Anabasis, a work devoted entirely to mercenaries (Xen. An. 4.5.13; 5.8.21). On both occasions this is not to refer to mercenaries or mercenary activity. In the first instance he used a related noun to denote protection (epikourêma), and to specify medical aid given to soldiers in distress, and second, verbally, ‘to be an epikouros’ (epi-epikoureô) or a helper for those who needed protection. Xenophon’s Hellenica is no different. On only one occasion is the term used as a noun indicating mercenaries, as in 369 BC an Arcadian statesman proclaimed that his people were traditionally fighters for others (Xen. Hell. 7.1.23). The oldest word for mercenaries denotes the traditional profession of the region. The epikouroi of Arcadia were proverbial. On all other occasions in Xenophon, it serves as a word denoting aid, succour or assistance (Xen. Hell. 4.6.3; 6.5.40, 47; 7.4.6). To reinforce the transformation, in the second century AD Arrian used epikouros with respect to aid received rather than to any type of soldier (Arr. Anab. 6.5.4). More tellingly, the word’s use had changed much earlier, contemporary with Xenophon: Plato’s epikouroi form the second hierarchical tier in his idealized republic and so could not have represented anything other than full and important members of his theoretical community (Pl. Resp. 415 a). It is little surprise that the Archaic term epikouros disappeared from later texts.

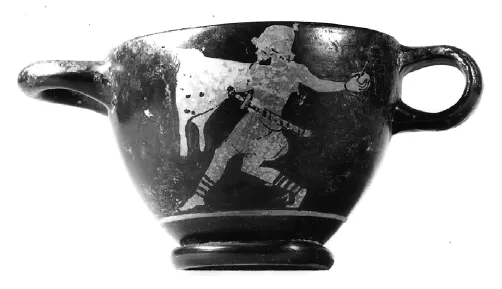

Figure 2 Mid-fifth-century BC Attic skyphos depicting a stone-thrower (petrobolos) carrying a sword and using an animal skin to protect his left arm (Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Inv. IV 1922).

By the later fifth century BC, the term xenos was applied to mercenary soldiers (RE, vol. 9a, pt 2, 1442–3, s.v. xenos). This word could denote a foreigner or a stranger in any context. It usually, but certainly not always, referred specifically to a Greek from another Greek community. It often described men bound to one another by ties of reciprocity and ritualized friendship (a guest-friend). The ritualized or guest-friend was always an outsider, bound to a family and household not by ties of blood, but by bonds of hospitality and reciprocity. There were other meanings. The Athenians referred to their subject-allies as xenoi in inscriptions dealing with the Delian League (Finley 1954: 104–5; Gauthier 1971: 44–79), though some have suggested that in this context xenoi meant mercenaries (Loraux 1986: 32). In either event they probably served for payment. Thucydides must mean these subject allies of the Delian League on occasions when he used the term (e.g. Thuc. 1.68.1–2; 7.13.2). In spite of these other meanings, Xenophon used the term exclusively of the mercenaries who served with him under Cyrus the Younger in his attempted coup of 401 BC. The Thracian mercenaries who defeated a Spartan division (mora) at Lechaeum on 390 BC were simply called to xenikon or the foreign corps (Xen. Hell. 4.5.11–18; Dem. 4.24; Ar. Plout. 173). Like epikouros there is a certain euphemistic quality to the term xenos. The notion of a mercenary as a ritualized foreign friend gave the hired soldier an elevated status and a special relationship with his employer. Clearly not all the Greek soldiers on the anabasis with Xenophon can have been ritualized friends of Cyrus, the Persians or even all the Greek generals on the expedition. It was, no doubt, much better to be the xenos of the Great King’s brother than a hired mercenary. Xenophon would have been keen to emphasize a special relationship. Xenos survived into the fourth century BC as a term for mercenaries. It was used often by Aeneas Tacticus writing in the middle of the century (Aen. Tact. 10.21, 12.2, 13.1, 3, 18.14) and even appears in the work of Arrian over 500 years later (e.g. Arr. Anab. 1.14.4, 24.4).

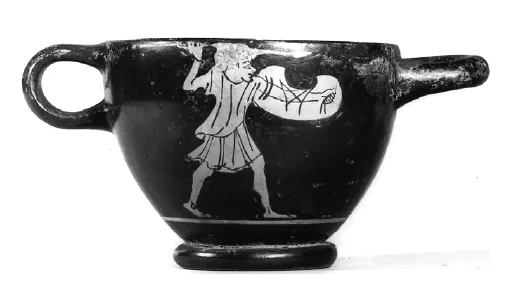

Figure 3 Mid-fifth-century BC Attic skyphos depicting a Thracian peltast armed with a crescent-shaped shield (pelta) and javelin (Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Inv. IV 1922).

The payment of regular wages became common in the fifth century BC. Wage payments were important sources of income for mercenaries. Herodotus had recognized that men served as mercenaries having been persuaded by wage payment (Hdt. 1.61.3). Thucydides also claimed that men were hired or persuaded by pay (Thuc. 1.60; 4.80.5). The wage-earning soldier and the mercenary soon became synonymous. Misthophoros refers to any man who drew regular pay, not necessarily mercenaries. Payments might come from jury service, Delian League embassies, temple-building, as well as soldiering. Thucydides used misthophoroi sparingly (Thuc. 1.35.4; 3.109.3; 6.43.1; 7.57.3, 9, 58.3). He first used the term of mercenaries in the speech of the Corcyraeans to the Athenians on the brink of war (Thuc. 1.35.4). They are undoubtedly referring to naval mercenary oarsmen. Naval warfare consumed vast amounts of resources. In the fifth century, naval warfare became closely associated with coined money for payment of crews who rowed in the fleet. These regular payments no doubt influenced land warfare, and infantry called misthophoroi appear first in Thucydides’ Histories in an action at Amphilochia in c. 426/5 BC (Thuc. 3.109.3). The term misthophoros became the most common word used of the mercenary in antiquity. Xenophon used misthophoros extensively in his Hellenica and occasionally in the Anabasis (Xen. Hell. 2.4.30; 3.1.23; 4.2.5; 6.9; 14). Ephorus, who also wrote in the fourth century BC, appears to have favoured the term misthophoros. His attribution of the invention of mercenary service to the Carians is indicative of this for, as he stated, they were the first to serve for wages (misthophorêsai), but the time to which he is referring in the mid-seventh century was well before the appearance of wages (misthos) or wage-earners (misthophoroi) in the eastern Mediterranean (Ephorus, FGrH 70 F 12).

Diodorus’ histories span the period of Archaic and Classical Greek history. Diodorus (floruit c. 50 BC) wrote long after the fourth century and was clearly influenced in his choice of terms by subsequent events in the Greek world, especially the Roman conquest of the Greeks. Following his fourth-century source, Ephorus of Cyme, he used the term misthophoros almost exclusively, even though he must have known about the earlier Greek historians who did not use this word. He tellingly called both the ‘bronze men’ of Herodotus, who were the allies (epikouroi) of Psammetichus from Caria and Ionia in the seventh century BC (Diod. 1.66.12), and Xenophon’s guest-friends (xenoi) serving with Cyrus, misthophoroi or wage-earners (Diod. 14.14.3). When he did use xenos for mercenary it often appears with the notation that such men were paid wages (Diod. 16.28.2). Diodorus’ use of misthophoros for mercenary is almost exclusive of other terms from the Archaic and Classical Greek periods.

Arrian (AD 86–160) also wrote long after the events he described. He too used misthophoros prolifically, although not exclusively. Arrian used xenos in conjunction with misthophoros, to produce a term meaning foreign wage-earner (xenos misthophoros). It is a conjunction found rarely before in Greek texts, though notably in a speech delivered by Demosthenes in 351 BC and in Aeneas Tacticus’ treatise on surviving a siege (Dem. 5.28; Aen. Tact. 12.2. See also Diod. 11.72.3). It is very close to a modern definition of a mercenary as it incorporates ideas of both remuneration and foreignness. Arrian used misthophoros and xenos to describe several of Alexander’s mercenaries, sometimes one term and sometimes the other. Then again, he used both terms to describe some of Alexander’s mercenaries (xenoi-misthophoroi). The reason has proved problematic for some historians. He may have used foreign wage-earners (xenoi-misthophoroi) to distinguish one group of mercenaries from other ordinary misthophoroi. It is possible that one term meant Alexander’s original mercenaries, those who came with him from Greece in 334 BC, and the other term meant men sent out after his initial invasion of Persia.5 Berve (1926: 144) suggested there may have been a military distinction, that each term represented a different kind of soldier, but Arrian seems to have used both terms fairly indiscriminately (e.g. Arr. Anab. 2.5.1, 9.1). Foreign wage-earners (xenoi misthophoroi) are listed separately from the other (Greek) wage-earners (misthophoroi) in the order of battle at Gaugamela in 331 BC (Arr. Anab. 3.9.4). Perhaps the terms did distinguish between Greeks and non-Greeks on the battlefield or Arrian’s source had made a distinction for simplicity between separate mercenary units. Whatever the answer, most significantly, foreign wage-earner (xenos-misthophoros) categorized a mercenary with more clarity than previous terminology.

Clearly we can identify that a chronological succession of terms was applied to the Greek mercenary from the seventh to the fourth centuries BC (Parke 1933: 20–1).6 Specifically, there was a development from the euphemistic fighter-alongside or ally (epikouros) to the more realistic wage-earner (misthophoros). The reason for the transition of terms initially stems from the meaning of epikouros. The verbal form means to act as a helper, to give aid, to help or to protect. Homer’s epikouroi were not mercenaries, b...