1

A COMMENTARY ON THE CLOSING FORMULA FOUND IN THE CENTRAL ASIAN WAQF DOCUMENTS

ISOGAI Ken’ichi

The waqf documents preserved in almost all the parts of the Muslim world contain rich information on the past social life of Muslim communities. These documents have attracted a wide range of specialists engaged in historical research into every aspect of the Islamic world, including the history of Muslim Central Asia. Aware of the documents’ importance as historical sources, several specialists in this area devoted themselves to studying waqf deeds drawn up at various times in the region. Rich and specific information drawn from the contents of these documents appears to have been well analyzed by scholars, mainly from socio-historical or socio-economic historical viewpoints.1 However, researchers have paid much less attention to both the external appearance and internal structure of the documents2 even though the form of a document sometimes gives information as valuable as that provided by the contents.

This chapter examines issues related to the closing formula often found in the waqf deeds of Central Asia after the sixteenth century. It aims to show how the teachings of the Hanafite school exerted influence on the form of the court document as composed in a region where this school enjoyed a dominant position for a long time.

The closing formula

The waqf deeds drawn up in Central Asia after the sixteenth century often include the same formula in their endings. Here, I will show the text of this formula in generic form, reconstructed on the basis of five documents whose dates range from the end of the sixteenth to the middle of the eighteenth century.3

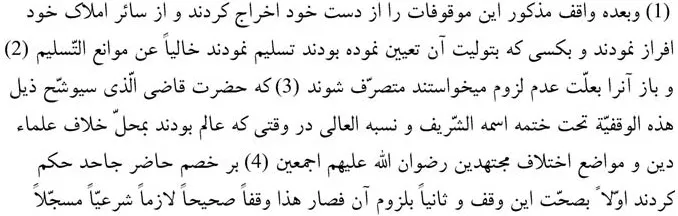

Persian text

English translation

(1) After [the wāqif’s statement that he had turned the legal status of the objects explained above from privately owned property into waqf,] the wāqif removed these properties from his possession (dast),4 set them apart from his other private properties, and delivered them to the one whom he had appointed to administer the waqf, having been free from anything that might prevent the delivery. (2) Then the wāqif wanted to put these properties changed into waqf at his own disposal again, under the pretext that [the waqf] lacked binding force or irrevocability (luzūm). (3) At this point, His Excellency the qadi whose noble name and sublime surname would adorn the bottom of this document under his seal, having known about the points where the disagreement and divergence among religious scholars and mujtahids – may God be satisfied with them all – had occurred, (4) passed judgment against the defendant who was present and denied [the claim of the plaintiff], first, that the contract of the given waqf had been made legitimately and, second, that the given waqf had acquired binding force. Then [the waqf mentioned in this document] became the legitimate (ṣaḥīḥ), binding (lāzim) and lawful (sharʿī) waqf provided with the sijill (musajjal).

The text can be divided into four parts, as demonstrated above: (1) the wāqif ’s declaration of delivery (taslīm), (2) the wāqif ’s intention of revoking waqf (rujūʿ), (3) the description of the qadi who passed the judgment and (4) qadi’s judgment (ḥukm) confirming the legitimacy (ṣiḥḥa) and binding force (luzūm) of the waqf.

The wāqif who intended to establish waqf according to the teachings of the Hanafite school had to acquire through a formal, or fictitious, lawsuit the qadi’s judgment affirming the binding force of the waqf to warrant its permanent continuation.5 The origin of this complicated and somewhat curious procedure can be attributed to controversy among three founders of the Hanafite school over the binding force of the waqf, as is alluded to in the following passage: “. . . having known about the points where the disagreement and divergence among religious scholars and mujtahids – May God be satisfied with them all – had occurred . . . .”

As will be discussed later in detail, Abu Hanifa, contrary to his two disciples Abu Yusuf and Muhammad al-Shaybani, had denied the binding force of waqf; therefore, jurists assumed that the issue must have been resolved by individual qadis. In other words, the decision whether the binding force of waqf was to be admitted or not was put into the hands of individual qadis. Thus, as far as the Hanafite school is concerned, the binding force (luzūm) of each waqf can be confirmed only by the judgment (ḥukm) of individual qadis, and these circumstances find their clearest expression in the closing formula in question.

On the other hand, Central Asian waqf deeds drawn up before the sixteenth century were usually accompanied by a separate sijill, that is, a document recording the judgment of a qadi.6 The word “musajjal,” found in the closing formula and meaning “being provided with a sijill,” suggests that the binding force of waqf was originally considered to be documented by a separate sijill.

The following section will describe these separate sijills attached to waqf deeds before the sixteenth century and show the process of transition from a separate sijill to the formula incorporated into the text of a waqf deed.

From the separate sijill to the closing formula

According to Hanafite jurists, the judgment confirming the binding force of waqf had to be acquired through a formal lawsuit. Ibn al-Humam (d.1457), the author of Fatḥ al-Qadīr, explains its process.7

The judgment of a ḥākim8 is acquired in the following manner: [a wāqif] delivers the property which he made waqf to a mutawalli and, after that, manifests his intention of revoking waqf. Then [the mutawalli] brings a lawsuit against [the wāqif]. Finally, the qadi to whom the lawsuit was brought pronounces the judgment in favor of the binding force of the waqf in question.

wa-ṣūratu ḥukmi al-ḥākimi . . . an yusallima-hu ilā mutawallin thumma yuẓhira al-rujūʿa fa-yukhāṣima-hu ilā al-qāḍ īʾ fa-yaqḍiya al-qāḍī bi-luzūmi-hi

The process consists of four elements: delivery (taslīm), revocation (rujūʿ), lawsuit (mukhāṣama or murāfaʿa), and judgment (qaḍāʾ or ḥukm). One would find these elements far more strictly reproduced in the separate sijills than in the closing formula incorporated into the text of waqf deeds. Here, I quote the part of the sijill – dated 9 February 1299 – attached to the waqf deed bearing the date 13 January 1299 as an example:9

I, Abu al-Fadl Muhammad b. Muhammad b. ʿUmar b. al-Mahmud al-Bukhari . . . pronounced a judgment in favor of the legitimacy and legality of this waqf and also in favor of the validity and binding force of this ṣadaqa concerning all the properties which were described to be waqf in the main text of the waqf deed . . . . The judgment was delivered as a consequence of a legitimate and lawful suit . . . which had taken place in my presence and which had been brought by the plaintiff whose claim had been permitted in law to be heard against the defendant, who as an answer to the plaintiff had denied the legitimacy and binding force of the waqf in question – in this case it is permitted in law to pronounce judgment against him because the defendant’s claim tends to the invalidity [of the waqf]. I came to the decision stated above when, with sufficient knowledge about the points of controversy, I exerted the ijtihād, which led to the conclusion affirming the legitimacy and binding force of the waqf in accordance with the pious imams of the past – may God have mercy upon them – who had upheld the legality of a waqf like this and the binding force and validity of a ṣadaqa in this form.

. . . ḥakamtu bi-ṣiḥḥati hādhā al-waqfi wa-jawāzi-hi wa-nafādhi hādhihi al-ṣadaqati wa-luzūmi-hā fī jamīʿi mā buyyina waqfīyatu-hu fī bāṭini ṣakki al-waqfi hādhā . . . wa-dhālika baʿda daʿwā ṣaḥīḥatin sharʿīyatin . . . jarat bayna yadayya min khaṣmin muddaʿin jāza fī al-sharʿi samāʿu daʿwā-hu ʿalā khaṣmin munkirin ṣiḥḥata-hu wa-luzūma-hu wa-sāgha fī al-sharʿi ijrāʾu al-ḥukmi ʿalay-hi māʾiluu ilā jihati al-fasādi wa-dhālika baʿda mā ʿaraftu mawāḍiʿa al-khilāfi wa-mawāqiʿa al-ikhtilāfi waqaʿa ijtihādī ʿalā ṣiḥḥati-hi wa-luzūmi-hi ʿamalan minnī ʿalā qawli man yarā jawāza hādhā al-waqfi wa-luzūma hādhihi al-ṣadaqati wa-nafādhi-hā min al-a’immati al-salafi al-ṣāliḥati raḥima-hum allāhu

The sijill cited above gives the full details of the process of this formal lawsuit. That a mutawalli appears as a plaintiff, while a wāqif is allocated the role of a defendant, and that the judgment is delivered as a result of the qadi’s own ijtihād are not clearly shown in the closing formula after the sixteenth century. On the whole, besides the detailed description of the lawsuit, these separate sijills have the essential feature which provides a striking contrast to the closing formula incorporated into the text of a waqf deed, that is, they are written in the first person in the name of the qadi who passed the judgment in favor of the binding force of the waqf in question.10 This feature – being written in the first person in the name of a qadi – appears to have been well preserved in the second half of the fifteenth century when the description of the lawsuit became drastically simplified.11

The fact that some Central Asian waqf deeds drawn up before the sixteenth century have a separate sijill in the first person, even though they also contain the description of the lawsuit in the third person at the end of their own text,12 clearly shows the significance of these separate sijills. At least, at that time including only the description of the lawsuit in the text of a waqf deed apparently could not give waqf the effect expressed by the term “musajjal” (lit., being provided with sijill).

In contrast to these precedent separate sijills, the later closing formula was neither written in the first person nor took the form of a separate document. The new feature...