1 The Japanese tattoo

Play or purpose?

Joy Hendry

Introduction

The tattoo is associated with play in many countries, and this frivolity has recently spilt over into Japan in a big way, especially among young people. In Japan, tattooing has a deadly serious side too, however. Defining the boundaries of play is a difficult enterprise, of course. One person’s play is another’s toil, and ‘play’ often incorporates a serious purpose beneath the apparent fun. Moreover, activities that amuse members of one society, or one sector of a wider society, may well offend a different one. The association between play and tattooing is highly ambiguous in Japan, complicated by a global resurge of interest in the subject, and this chapter will seek to explore the meaning of this curious example of Japanese playfulness.

Japanese tattooing attracts the attention of artists far and wide for its beauty, and for the skills of its creation. Although tattoos are found in various parts of the world, in various degrees of elaboration, the Japanese version is undoubtedly among the most aesthetically developed. Years ago historian of tattooing, W.D. Hambly, wrote, ‘no other style can compare in colour, form, motion, or light and shade of background’ (1925: 312; cf. Morris and Marsh 1988: 84), yet the reaction of many Japanese people to the whole idea of tattooing is still negative. A friend with whom I was staying when I began this investigation, in 1991, looked sickened when I mentioned the subject. Others warned me very seriously against it.

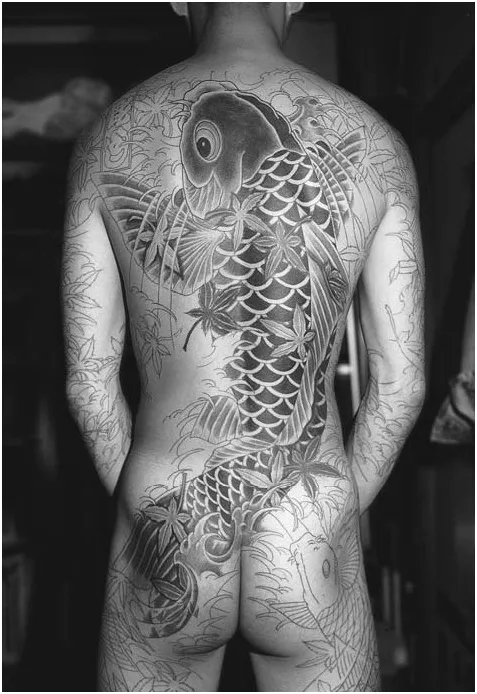

The two opposing attitudes stand, of course, for different points of view, and there are several others that could be mentioned, but they introduce the theme by way of epitomizing the ambivalence that surrounds the nature of Japanese tattoos and the people who wear them. A Japanese tattoo, in its full glory, covers the back and several other adjoining parts of the body. It depicts folk heroes, religious figures and a variety of flora and fauna, outlined, first in the blue-black of ink beneath the skin, and then coloured in with a combination of brilliant dyes. There is usually a main character depicted on the back, but the design will be picked up, or offset, with other smaller figures on the arms, chest and thighs. More limited Western-style tattoos, sometimes called ‘wan-pointo’, though they may cover several square inches of flesh, have recently gained popularity.

All this is often entirely obscured by clothes, however, and people with tattoos are barred from many public bathhouses, so the full effect may be reserved for a privileged few on a limited number of occasions. Some of these occasions are specifically associated with ‘play’, such as a contemporary example found in ‘club culture’, where it is possible to admire tattoos that glow in their full glory only under ultra-violet light.1 Other such occasions are far more serious in their purpose and may indicate quite sinister intent. Let us first examine some of the historical reasons for this propensity to hide what may in effect be works of art little different from the famous Japanese woodblock prints liberally on display in galleries around the world.

A short history of tattooing in Japan2

First mention of Japanese tattooing is to be found in the third-century Chinese chronicle, the Wei Chih, where the Japanese, ‘the Wa’, are described as follows:

men, young and old, all tattoo their faces and decorate their bodies with designs . . . The Wa, who are fond of diving into water to get fish and shells, also decorated their bodies in order to keep away large fish and waterfowl.

(McCallum 1988:114)3

Later reports emphasize the decorative nature of the designs, rather than their protective qualities, and the fact that the position and size of the patterns indicated differences of rank (ibid.).

However, the Chinese disapproved of tattooing, and indeed any puncturing of the skin, and in the first Japanese chronicles, which were written from the seventh century, it was evident that these Chinese attitudes had been adopted in Japan too. References to tattooing in the Nihonshoki, for example, were about its use as a form of punishment and showed indications of the barbarism and savagery it was supposed to represent. Otherwise, tattoos were associated particularly with the people who inhabited the peripheries of Japan, namely the Ainu, who tattooed their faces and arms, and the Okinawans who tattooed their hands and feet (McCallum 1988: 116–7).

For mainland Japanese, over the centuries, tattooing was used as a punishment for heinous crimes such as murder, betrayal and treason. It was also used to brand slaves and to distinguish groups of outcast people. Such tattoos seem to have been much more limited in size and elaboration, however, composed merely of a line or a series of lines, depending on the severity of the punishment. In a 1716 code, tattooing was associated with relatively minor offences such as ‘flattery with ulterior motives’ (van Gulik 1982: 10), fraud and extortion, and there is some evidence to suggest that by this time people with tattoos had begun to band together and also to have more elaborate tattoos done over the ones which marked their catalogue of crimes. Tattooing as a punishment was finally abolished in 1870 (ibid.: 12).

During the Edo period (1600–1868), tattooing became evident in the context of play, with reference in the writings of Ihara Saikaku, and depictions of the full-body tattoo in the wood block prints of Utamaru (Richie and Buruma 1980: 14–21). It seems to have flourished in the pleasure quarters, first in a small way as a mole or a name – for a concubine to pledge devotion and loyalty to her master, likely as not married officially elsewhere (ibid. cf. McCallum 1988: 118) – and then as a kind of full-body rejection of the wider, highly organized society into which some people just did not fit. Those with tattoos would be in clearly marginal positions: the wandering samurai with no leader, second sons of merchants with no business to inherit, or people associated with transition such as palanquin bearers, firefighters and construction workers.

Figure 1.1 A full-body Japanese tattoo, with main theme on the back, picked up again on other parts of the body. This example is a koi (carp), and illustrates the process of making a complete ‘canvas’ before gradually filling in the colour. As the bearer of such a tattoo moves, the fishes depicted on his body may appear to be swimming

Many commentators point to a connection between full body tattoos of the time with the Suikoden, a Japanese translation of the fourteenth-century Chinese story now known in English as the Water Margin, legendary tales of a Robin Hood type figure called Sung Chiang and his 108 followers. These stories were popularized in Japanese in ninety volumes by Bakin, illustrated by Hokusai and, later, with even more impact, in 108 individual prints by Kuniyoshi.4 Some of the favourite characters wore splendid tattoos, and several of these characters have since been chosen as the centrepiece of tattoos in real life.

During this period, tattoos were actually banned several times, along with restrictions on other activities such as kabuki, woodblock prints and elaborate clothes, in the repeated official condemnation of the world of pleasure. In response, merchants developed elaborate linings for their austere coats, subtly to display their wealth, and others expressed their rejection of the rules by elaborately decorating their bodies, which they then concealed with clothes. The wider society disapproved – partly expressing a notion of sin attached to the piercing of the skin – but like the outlawed heroes of the popular legends, those with tattoos may well have seen themselves as forces for good in an overly authoritative world.

One group of people who wore tattoos, and whose designs distinguished their particular associations, were the firefighters of the time. They were, of course, absolutely vital because of the serious threat fire was and is in a country where most of the houses are built of wood, but they were a rough and rowdy crowd, and ordinary people were wary of them. Nevertheless they provided an important service, and tattooed or not, people were obliged to seek their help. This relationship typifies the ambiguous attitude of the wider society to tattooing, and the marginal position those with tattoos often held.

From 1868, under a perceived notion of Western disapproval, tattooing was again prohibited as a barbarous custom and many of the chapbooks used by the artists were forcibly burnt. However, foreigners often liked the tattoos they saw and they even sought out people with tattoos to employ as palanquin bearers. Furthermore the tattoo artists began to receive foreign customers, some as illustrious as King George V of England, when he was Duke of York, and Nicholas II of Russia, when he was Tsarevitch, cousins who were serving together a period as sailors (Brain 1979: 52; McCallum 1988: 124). In fact, many European tattoo artists have been influenced by Japanese techniques and designs since that time, some even travelling to Japan to learn more about them.

In Japan itself, tattooing remained prohibited until 1945, but several groups of people continued to practise it covertly. The various skills had been divided between different artists, as with woodblock printing, but during this period individual artists learnt to master all the techniques required in order to diminish the likelihood of revealment. Unlike in Europe, their customers were not soldiers and sailors, who were rather part of mainstream society, but members of the underworld and people in other marginal positions.

After the Second World War, tattooing became associated particularly with the yakuza, or gangsters of the Japanese mafia, who themselves carry a somewhat ambiguous image – partly of terror, partly romantic, through their portrayal in films and television dramas, and their self-styled chivalrous path of ninkyōdo (see, for example, Kaplan and Dubro 1986; Raz 1992). Their activities are definitely associated with the world of play, but in forbidden arenas of gambling, prostitution, protection and drugs. There are other occupational groups who are said to wear tattoos, such as construction workers, steeplejacks, sushi-makers and prostitutes, but the predominant image was until very recently with the yakuza.

Since I first presented this chapter at the Berlin conference in 1991, tattoos have become increasingly popular with young people in Japan, many of whom choose Western motifs, which are thereby distinguished from the more traditional Japanese variety and apparently carry less opprobrium. They are called ‘tattoo’, using the English word, and some artists confine their work to these smaller examples of the genre, offering a range pretty much like those found in Western countries. Their clients are influenced by Western rock artists who sport tattoos, and one of my Japanese students mentioned the US band Motley Crüe as having inspired his own interest. The main focus of this chapter is concerned with the more specifically Japanese tattoos, however.

A contemporary impression

With this historical overview as background, I would like to turn now, first, to the world of tattooing as I observed it during a period of field research in 1991, and from that albeit very limited experience, examine some of the rationale behind its practice. My contacts in this world were rather few, but they were good ones in the sense that they were extremely co-operative. As might be expected, there were no official figures about the numbers of people involved, but estimates of my contacts put the number of artists in Japan at that time between 120 and 300, mostly men, and mostly located in a few urban centres.

At that time, there was no advertising, very few entries in the yellow pages, and the artists hung no signboards over their studios. In the last few years of the 1990s artists specializing in Western tattoos began to appear and advertise themselves quite openly on the streets of many Japanese cities, but in order to meet my best informant in 1991, things were a little clandestine. A personal introduction from an artist in Oxford provided me only with a telephone number, and when I called I was instructed to take a taxi from the nearest station to a specific street corner, where I should phone again. I was then collected by the deshi (apprentice), who led me through several back streets and eventually up an outside staircase into a firstfloor apartment.

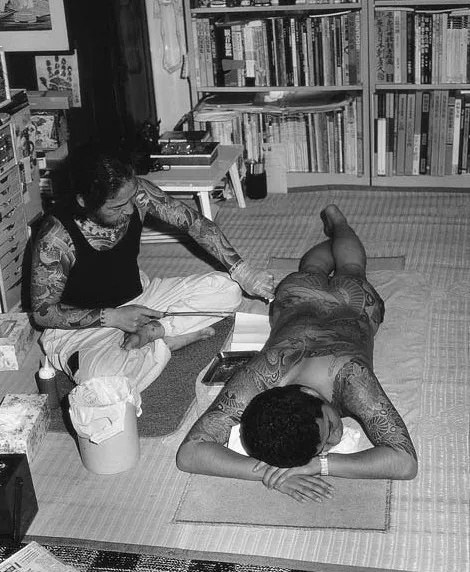

There are two chief words for tattooing in Japanese. The first, irezumi, literally the insertion (ire) of ink (sumi ), is the one associated with punishment and the general disgust of the wider public for the practice. The second, horimono, is based on the verb horu, to engrave, puncture or incise, also used for carving, engraving and sculpture, so that this word has much more positive, artistic connotations. The character for horu appears in the adopted names of the artists. Some examples are Horicho, Horiuno, Horibun and Horigoro, names that are passed on through the generations. The one I found in the first-floor apartment was Horiyoshi III, a man who by the end of the decade was to become probably one of the best regarded tattoo artists in the world. A photograph on the wall depicted his predecessor and mentor, Horiyoshi I.

Figure 1.2 The artist Horiyoshi III at work in his studio

Horiyoshi III claimed to have some 2000 clients, on whose bodies he was working, but he had by then completed 20 full-body tattoos and these customers met two or three times a year, with the artist, in a sort of reunion. A photograph of this group also hung on the artist’s wall, alongside a polished plaque with the names of some of his earliest creations, who apparently purchased it for him as a way of showing their gratitude. The deshi described the feelings of these men in buying the plaque almost in terms of worship, and neither argued when I suggested that the artist was on his way to becoming a sort of kami-sama (deity).5 It certainly became clear when I asked if I could photograph his work, and therefore the bodies of his clients, that the decision to allow me was his, totally without reference to the canvas, except where I asked!

The process of acquiring a full-body tattoo is a long and complicated one requiring between 150 and 200 hours of work, usually carried out at the rate of one or two hours weekly and costing (in 1991) some 10,000 yen a time, adding up to a total basic ...