![]()

1

Introduction

Science is nothing but trained and organised common sense.

— T. H. Huxley, 1825–1895

Mere awareness of research is not sufficient for a profession that seeks truth and knowledge. Research is an activity concerned with systematic gathering of information about matters in which one is interested. It does not in itself lead one to the truth or to explanations for events.

Historically, the search for truth has taken many forms. Our ancient ancestors searched for truth among the elements, the gods represented by the sun, wind, earth, fire, animals, rocks, and trees—all vividly captured in mythologies of the Australian aborigines, the First Nation tribes in North America, the stone tablets of the Middle Eastern kingdoms, and so one. This represented one approach, or paradigm. If one were to not look to external sources such as these in the quest for knowledge or truth, then an alternative approach might be to look within oneself for the answers (i.e., introspect). Two hundred years ago, introspection was taken seriously and considered an important approach to discovering knowledge. The scientist would ponder and reflect on a yet-unsolved question (e.g., What do I do when I read the word irresistible? What happens in my mouth when I speak the sentence “Mary has a little lamb”?). The answer to this question (i.e., whatever the person thought he or she did when reading this word or speaking the sentence) would be taken as knowledge about the reading or speaking process. Introspection is, of course, wholly inadequate as an approach or paradigm to discovering truthful, factual knowledge because people vary and disagree among themselves. This paradigm also provides no basis for testing the truthfulness of this information because the information is private and really only known to the individual volunteering this information. It is also very difficult to distinguish this type of truth from the truth of dreams, hallucinations, and other private experiences. So, sometime around the beginning of the 20th century, a group of learned philosophers debating the question of truth decided it was crucial that knowledge be observable and measurable. This led to behaviorism, a school of thought that dominated research and thinking through the 1970s. Dissatisfaction with simply reporting observable behaviors eventually led to the emergence of new approaches that admitted the role of mental processes and their measurement in the mid-1950s. In psychology, this was called cognitive psychology.

Although the quest for truth has taken many paths, two broad groupings encompass the vast array of different beliefs and views on what constitutes truth and how to get at it. Basically, one group adheres to a scientific doctrine and the other consists of several doctrines, many of which accept truth as defined by introspection and the self.

Professions adhering to a scientific doctrine accept that adherence to science means that the search for truthful knowledge must accord with set of agreed principles, guidelines, and criteria for defining knowledge. However, this identification with science as the basis for defining knowledge is clearer in some professions than in others. Whether a discipline or profession attains the status of being a science is a related, but separate, issue. The goal of striving for scientific status by a professional group is, however, not a trivial matter, particularly in the case of the public being encouraged to accept that a profession’s knowledge base is dominated and subject to control by scientific standards.

SPEECH AND LANGUAGE THERAPY AS AN APPLIED SCIENCE

The study of speech and language therapy draws heavily for its theoretical bases from the domains of psychology, medicine, linguistics, and, to a lesser extent, sociology. A traditional view of the speech and language therapy discipline is that it acquires its theoretical perspective on a particular condition from one of the other domains and applies this knowledge to the treatment of a communication disorder. Speech and language therapy is an applied science in the sense that the study and practice of speech and language therapy is predicated on adopting relevant theories and methods from other disciplines and applying these to the context of abnormal communication. The nature of the relationship between speech and language therapy and other fields suggests two things:

• Progress in areas of speech and language therapy could be secondary to the developments in these other primary disciplines.

• The definition of the scientific status of speech and language therapy could be contingent on how successfully these other domains have attained scientific status within their own fields.

It is reasonable to posit that the scientific disposition of speech and language therapy reflects the scientific status of the theories and methods it borrows from other disciplines. These disciplines vary among and within themselves as to how they approach investigating problems, which in turn has an effect on whether their ideas are considered to have scientific merit. For example, let’s contrast linguistics and psychology. In linguistics, introspection still forms a major approach in situations such as judging the grammatical correctness of sentences, whereas psychology traditionally relies on experiments to inform about the nature of grammatical judgments.

Although speech and language therapy has a codependent relationship with other disciplines, the modern speech and language therapist has a legitimate role as a researcher, someone who is capable of making independent contributions to theory development, whether or not it has a transparent relationship with practice.

WHO WE ARE AND WHAT GUIDES OUR CHOICES IN PRACTICE

At some point, members of the speech and language therapy profession must reflect seriously on what it means to be a discipline with a scientific basis and how this is determined. If the scientific identity of the speech and language therapy profession were uncertain, then it follows that its members could become confused when asked, “Are speech and language therapists clinical scientists? care-givers? teachers? remedial educators? Are they spiritual healers? Are they simply heart-on-sleeve do-gooders? Do they work within the same realm as those in alternative therapies? Who decides whether they do or not? How do we differentiate what we do from the group of caregivers and healers who are perhaps not counted among the group of orthodox (i.e., scientific) professions? In what way is the practice of speech and language therapy scientific? What are the markers of scientific practice?

Were science not the guiding hand in speech and language therapy practice, then it is difficult to imagine what could take its place as the guiding doctrine. All that would be available to clinicians would amount to nothing more than a set of arbitrary rules to define good practice. The image of speech clinicians guided by intuition rather than more principled and tested methods would persist. Ignorance and confusion would prevail among clinicians; they would not know why certain therapy ideas do or do not qualify as valid methods of speech therapy practice (e.g., dysphagia, group therapy, computer-based therapy, reflexology). Why are some therapeutic solutions accepted more readily than others? For example, compare the Lee Silverman Voice program designed to remediate the soft-spoken voices of Parkinson’s disease patients (Ramig, Countryman, Thompson, & Horii, 1995) and the Tomatis method (Tomatis, 1963). Both treatment methods claim to ameliorate patients’ vocal conditions (and more—in the case of the Tomatis treatment). At the time of this writing, there were only two efficacy studies on the Lee Silverman method, one of which was published by the group advocating this new treatment and the other study, though by a different group of researchers, was equivocal. The Tomatis method is presented in many more publications (admittedly in nonprofessional journals), and yet it remains the more obscure treatment of the two methods. Why? What is informing this preference?

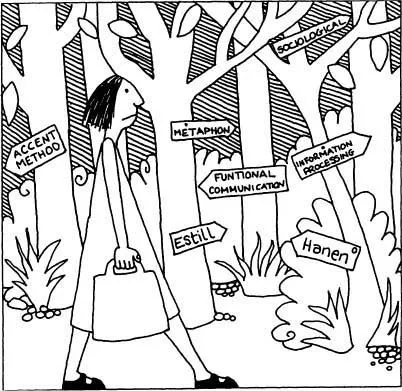

Clinicians debate the value of qualitative versus quantitative approaches and real-life intervention approaches versus formal decontextualized clinic-based intervention approaches. Issues like these can divide communities of clinicians because of closely held beliefs that one approach is vastly superior to another. These are complementary perspectives of a patient, and yet there are clear differences in the core values and preferences expressed by different clinicians about how best to approach patient management. Situations like this make it important that clinicians grasp the meaning of their professional actions beyond simply what they are doing and what appears congenial for their patients. The focus has to be on how we think about our patients. Besides thinking, it is also essential for clinicians to have a language for expressing why some treatment methods are more valid than others (see Fig. 1.1).

FIG. 1.1. Lost in the therapy wilderness.

RESEARCH AND SCIENCE EDUCATION OF SPEECH AND LANGUAGE THERAPISTS

Clinicians’ engagement in and appreciation of the importance of research is relatively recent. The value of research does, however, appear to exist in a vacuum when it exists without reference to any greater guiding meta-principle or philosophy. This state of affairs may go some way toward explaining why disagreements about therapy approaches tend to focus on superficial aspects of treatments or procedures rather than on their intrinsic scientific value. Some of the confusion appears to be due to a failure to discriminate between research as an activity and research as a part of a greater scientific endeavour. Confusion over research and methods of scientific inquiry is also evident in understanding the difference between outcome and efficacy studies. The ready adoption of new therapy approaches based on face validity (i.e., the approach appears to be useful to the patient on the surface rather than on the basis of any scientific explanation for its efficacy) is also an indication of a certain scientific naïveté.

In countries such as the United Kingdom and Australia, most clinicians encounter research when they take undergraduate courses in statistics and research methods. A smaller number have the opportunity to conduct research projects, usually to fulfill the requirements of an honors degree. A typical therapy course introduces statistics and research methods quite independently of other subjects in the curriculum. The motivation for teaching these subjects is often described in course handbooks in terms of equipping the student with skills to complete a research project to fulfill course requirements.

The present approach to educating clinicians presents certain inherent difficulties starting with selection interviews through the nature of instruction. Speech and language therapy courses that still conduct interviews as a part of the process of selecting students for a course are undoubtedly applying criteria that the assessors believe will produce the “right” type of clinician. This belief means we do not know, for example, whether the characteristics favored by these selection committees predict student success in the course or success as a professional.

In regard to the nature of instruction, many courses offer students courses in statistics and research methods. These are very important courses, and, if taught effectively, they have a major positive and enduring impact on the student clinician’s thinking. A problem for students entering an introductory statistics course in speech therapy, however, is that they often have to confront new material in several domains simultaneously, such as statistics, research methods, and speech therapy subjects. In addition, students bring to the subject the usual collection of well-known misconceptions and reasoning fallacies. Not surprisingly, students typically express a loathing for statistics, confusing it with mathematics, and fail to see the relevance of both research methods and statistics to the professional work. In consequence, some students’ academic self-esteem, although generally good in other subjects, is low in statistics and research methods.

Courses vary in how much time they give to covering topics related to the philosophy of science and its methods. It appears to me the greatest failure in many conventional courses is the failure to help students make a connection between the concepts expressed in statistics and research methods courses with other clinical courses. Students rarely make this connection for themselves, and ultimately students go on to become clinicians who regard these subjects as being largely irrelevant to clinical practice. Statistics and research methods are regarded as tools solely for the researcher’s use. How many lecturers incorporate statistics in teaching clinical problems, such as how to perform a McNemar test on client data to assess whether the client has improved in therapy? The concepts that the clinician and the researcher are both clinical scientists and that both are players in the larger scientific arena are rarely fostered in therapy education. One consequence of this conduct of teaching is the perception by students (and later clinicians) that there is a schism between research and speech and language therapy practice.

Some educators may feel that the dichotomization of clinicians into clinicians and scientists or clinicians and researchers is justified. It then becomes difficult to ignore the rather truncated situation of educators speaking keenly to speech and language therapy students in terms of hypotheses, models, and theories when minimal attention is given to developing the student’s understanding of these terms. Mathews (1994) brought these points to the fore when he argued for an improvement in science teaching through the teaching of the history and philosophy of science:

Knowledge of science entails knowledge of scientific facts, laws and theories—the products of science—it also entails knowledge of the processes of science—the technical and intellectual ways in which science develops and tests the knowledge it claims. (p. 3)

Although Matthews made these points when deploring the fact that students who are engaged in basic science courses graduate with little understanding of science, much of what he says also applies to health science courses. In other words, most health education programs offer students the small picture (e.g., the opportunity to undertake a research project) and rarely the big picture (e.g., the philosophical and historical context that embraces and defines the meaning of research activity).

One solution to this situation is to provide a broad prestatistics (e.g., a critical thinking skills course) course that introduces general principles of inquiry in a way that is decoupled from pure statistics. Such a course would teach valid thinking and address scientific thinking as one instance of valid thinking. Student clinicians and would-be researchers would both benefit from a course in scientific thinking as preparation for follow-on courses in statistics, research design, and research projects.

This type of learning, however, would have a much better chance of influencing thinking if the concepts explained in a scientific thinking and/or research methods course were considered with other subjects taken by the student. It would therefore be desirable for speech and language therapy educators and clinical tutors to repeatedly illustrate and express these concepts within various speech and language therapy contexts. This means that the presentation of a clinical disorder topic in a therapy course should include an evaluation of the arguments, identify theoretical predictions, and assess the evidence and question the claims made. This would be in addition to providing students with factual information about the disorder under consideration. Making this link between scientific thinking and other clinical subjects in speech therapy is important because research in thinking suggests that the transfer of thinking skills to other contexts rarely occurs spontaneously (Nickerson, 1987). Giere (1997) also asserted that scientific reasoning, like any other skill, can be acquired only through repeated practice.

Application of thinking skills in a variety of contexts (academic and practical) is also thought to be necessary for promoting the transfer of knowledge between subjects or contexts (Baron & Sternberg, 1987). Helping students make this link with science would ideally be among the main education goals of educators delivering a speech and language therapy course. It would also require educators to view their role as being facilitators in changing student’s thinking. This task cannot, however, be left solely to the one lecturer who takes the research methods course. Mathews (1994) identified three competencies that he believed would assist educators in their teaching of science to students: a knowledge and appreciation of science, some understanding of the history and philosophy of science, and some educational theory or pedagogical view that informs their choice of classroom activities.

In speech and language therapy courses, the primary emphasis is traditionally on students receiving an account of a particular speech disorder, its diagnostics, and treatment, usually, less emphasis is given to discussions about the methodological issues, the standard ...