1

THE GEOGRAPHY OF EUBOIA AND THE ERETRIAS1

Euboia

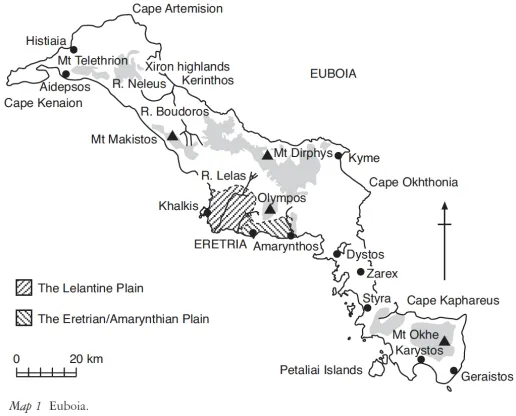

The island of Euboia (Map 1) extends for some 220km parallel to the coastline of Boiotia and Attica on the Greek mainland opposite,2 to which it is presently linked by a swing bridge across the narrowest part of the Euboian Channel, which is known as the Euripos, as well as by a suspension bridge, constructed in the 1980s, farther to the south. The Euripos was first bridged in 411/10, and the structure was subsequently repaired or renewed several times.3 The Greeks believed that the island (Figure 1.1) had once upon a time been violently torn away from the mainland as a result of earthquakes, and these are indeed still of frequent occurrence. The presence on the island of a number of thermal springs that both in ancient times and today attract tourists to try ‘the cure’, are a legacy of its seismic history (Figure 1.2).4 Its area is 3,770 km2, a large island by Mediterranean standards.5 It varies between about 60km at its widest to 3.2 km at its narrowest point. But it was its length that most impressed the ancients, and so it was sometimes called Makris (‘Long’ Island). Over its history it was given some seven different names, although only Euboia, Makris/Makra and Abantis/Abantias (and perhaps Ellopia) are likely ever to have applied to the whole island. Apart from Euboia, Abantis was the most commonly used, especially by poets. Although Homer refers to the island as Euboia, he calls the inhabitants Abantes. The Canadian Euboian specialist W. Wallace believes that the variety of names reflects the political separateness of the island’s regions and the difficulties of intercommunication. The name Abantis persisted, perhaps, because the area was traditionally associated in later times with the warlike Homeric Abantes.6

Figure 1.1The Euripos narrows and the old swing bridge at Khalkis.

Figure 1.2 Hot springs erupting at the site of the ancient spa on the coast at Aidepsos.

Mountains

As is the case with most of Greece, Euboia is very mountainous with only a few small plains, which in historical times were controlled by four principal poleis, Histiaia, Khalkis, Eretria, which between them held the largest and most fertile plains on the island, and Karystos. Although the latter is generally considered one of the principal city-states, its cultivable land was quite restricted. On the other hand, Kerinthos, which similarly had only a smallish plain, was never of great significance politically, was never regarded as a polis and was dependent on its larger and more powerful neighbours during most periods of its history. By the sixth century, it was certainly a dependency of Khalkis.7 The extensive tracts of rugged terrain separating the towns on the island were undoubtedly a significant reason why there was no real movement towards unity on the island until late in the fourth century (Figure 1.3).

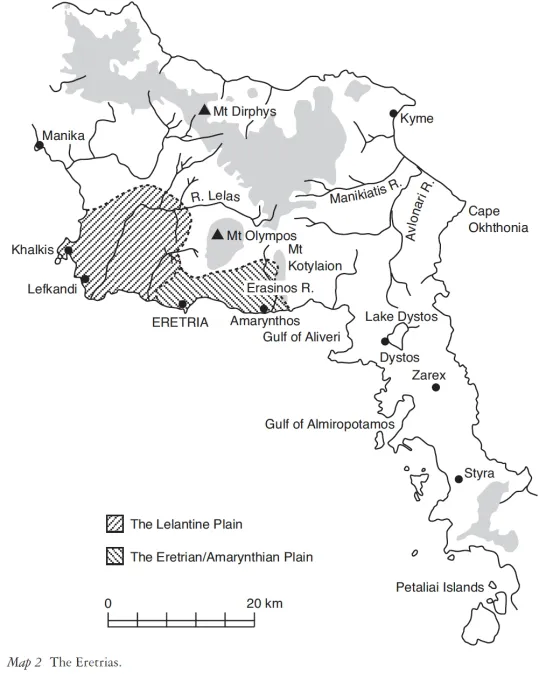

In the far north-east8 is the large mountain known in ancient times as Telethrion, which Strabo9 unambiguously locates in the Histiaiotis and which rises to an altitude of 970m. It is an offshoot of the Knemis Range in Epiknemidian Lokris on the mainland opposite. A series of ranges thrust themselves out from Telethrion. One to the west ends as Mt Likhas on the Kenaion Peninsula, another to the north forms the promontory of Artemision (Figure 1.4), while a third, today called Kandeli (1,209 m), extends south-eastward. In ancient times, it was known as Makistos.10 Other spurs and ridges extend out from it in a wide arc to the east and then curve around the north coast to link with Mt Dirphys (1,962 m), the highest point on the island (Figure 1.5), across the eastern and southern flanks of which were the marches between the territory of Khalkis and the Eretrias (Map 2). This chain then continues southward, although at a lower altitude, by way of the narrow neck of territory on which are located the considerable towns of Zarex and Styra (demes of Eretria by the fourth century), finally to connect with the most southerly of the great mountains of Euboia, Mt Okhe (1,398 m) in the Karystia. In the middle of the large amphitheatre formed by Dirphys and a range of moderately high ridges, presently called Servouni (in ancient times, Kotylaion)11 and which terminates on the coast near the important town of Amarynthos, there rose another high mountain, Olympos, in the Eretrias proper (1,172 m). Close to the east coast of the Eretrias and somewhat isolated rises Mt Okhthonia (771 m).

Figure 1.3 The ancient pass between Khalkis and Kerinthos.

Figure 1.4 Cape Artemision and the Straits of Oreoi.

Figure 1.5 The Throne of Hera at the summit of Mt Dirphys.

Plains and lowlands

There are only four significant plains on the island and, clearly, they are of the greatest importance as factors influencing its history. The most famous was the Lelantine Plain, an area of fertile grazing and agricultural land that lies between Eretria and Khalkis. On it, between these cities, lies the very important prehistoric settlement at Lefkandi, which has yielded finds of a richness that is almost unique for the so-called Greek Dark Age of the eleventh to the ninth centuries, testament to the prosperity provided by the plain as well as overseas trading. Its destruction led to the rise of Eretria. It is no accident that the best-known ‘event’ in the early history of Euboia, the so-called Lelantine War, takes its name from this plain for control of which it was fought. It is a part of the semicircle of lowlands and coastal plains enclosed by the peaks and ridges of Makistos, Dirphys and Kotylaion. Cut off to some extent from its most easterly sector, known as the Plain of Eretria (or Amarynthos) south-east of Eretria, by the mass of Mt Olympos, it was (and is still) a very fertile region, ploughed for the barley for which in later centuries Eretria was renowned (Figure 1.6). Its soil is deep and thick, as Theophrastos observed.12 Nineteenth-century travellers wax eloquent on its fruitfulness:

Figure 1.6 Barley and vegetable crops on the Lelantine Plain near Myktas.

Our course lay through the famous Lelantine Plain which, in spite of the rain, was seen to be a paradise. Such vines and fig trees and, further on, such grain fields! I had not seen the like in Greece. It is no wonder that it was a bone of contention almost before the dawn of history.13

It was on the pasturage of the upland fringes, on the slopes of the surrounding foothills, and on an extensive area of irregular terrain north of Khalkis called the Diakria that were located the horse-rearing lands of the Hippobotai, as the Khalkidian aristocrats were called. Two other areas of relatively flat land are in the north and north-east of the island, one around the town of Histiaia and the other the Plain of Mantoudhi near Kerinthos (Figure 1.7). They are separated by ridges of hill land, presently called Korakolithos and Xeronoros, and were famous in antiquity for the viticulture carried out on the surrounding hill slopes.14 Karystos in the far south of the island had its own modest plain that supported its smallish population. But Kyme on the Aegean coast north of Eretria, which must in most periods have been insignificant almost to the point of being non-existent, had no coastal plain and the inhabitants had to rely on narrow strips of flat land along the river valleys for cultivable terrain.15 The fourth, which lies within the Eretrias, is a fertile intermontane valley plateau, stretching from the head of the Gulf of Aliveri northwards via Lepoura and Avlonari to the modern town of Kipi.

Rivers and streams

As might be expected from the description of the island so far, Euboia is not a land of notable rivers. The largest is the Boudoros, which w...