1

STATE ENTERPRISE RESTRUCTURING

Renegotiating the social compact in urban China

Barry Naughton

‘Enterprise restructuring’ is the most recent of a series of Chinese policies designed to improve the performance of state-owned enterprises. As such, it has sometimes been hard to distinguish from its predecessors, and opinions have been mixed as to whether it has succeeded, indeed even as to whether it has been systematically pursued.1 In fact, as this chapter will make clear, the programme of enterprise restructuring that developed with increasing velocity during 1996 represents a major change in the relationship between enterprise and worker in urban China, and thus amounts to a fundamental renegotiation of the entire urban social contract. Whether or not enterprise restructuring results in dramatically improved economic performance, it has certainly changed the basis of social relations in urban China and its importance is guaranteed on this ground alone.

Enterprise restructuring reflects deeply rooted trends in the Chinese economy. Its impact depends partly on central government policy stance, but more fundamentally on the working out of these powerful economic and social trends. Central government policies have cleared the way for these forces to reshape urban social relations, by removing ideological blockades, by creating a (rickety) framework for social service delivery outside the enterprise, and by sanctioning the flow of resources into welfare-like job creation programmes. However, the key forces driving the process lie outside the scope of government policy. They include a more intensely competitive product marketplace, new opportunities for urban residents in higher-income occupations, increased job market competition for urban residents from rural migrants, and the elimination of constraints on enterprise hiring and (especially) firing. These forces will continue to drive enterprise restructuring forward, albeit at an uneven and inconsistent pace.

State enterprise restructuring has already affected the fundamental relationship between the government and the urban citizen. The nature of the urban social contract has been profoundly altered, and yet there is no clear consensus on the new social forms that are emerging. It is relatively easy to track the modifications in central government policy toward restructuring. We can get a good sense of the most important outcomes, including changes in employment and unemployment. Finally, we can clearly see that the actual outcomes of restructuring are predominantly the product of local government action, and we can trace the main forces operating on local government decision-makers. Thus, enterprise restructuring gives us significant insight into the political economy of Chinese decision-making and specifically the interplay between national and local forces. But enterprise restructuring also has profound implications that go beyond the immediate interplay of political and economic forces. Enterprise restructuring has been the means by which the fundamental urban social contract has been dissolved, and only partially reconstituted. Whether the new terms of urban citizenship in China turn out to be stable and viable cannot yet be determined.

The process of enterprise restructuring

Enterprise restructuring refers to a cluster of policies that have as their common objective clarifying ownership relations in public enterprises. At one end of the spectrum, restructuring can be as mild as so-called ‘corporatization’, converting a previously bureaucratically run state-owned enterprise (SOE) into a company with defined ownership shares and a board of directors to exercise control. Such corporatization is consistent with continued exercise of control by the same government agencies as before, simply requiring these agencies to establish institutions that give the enterprise more legal independence and create some possibility that an ‘arm’s length’ form of governance could develop. At the other end of the spectrum, restructuring can include overt privatization, with a new set of private owners replacing the vaguely defined public interest. In between, a range of alternatives includes mergers, consolidations, and conversion to employee-owned joint stock companies. Typically, restructuring includes some real changes in the scale of the enterprise operation, and particularly a reduction in the workforce. In some cases, bankruptcy and plant closures are the main outcome. Diversity is a prime characteristic of the restructuring process.

Central government policy

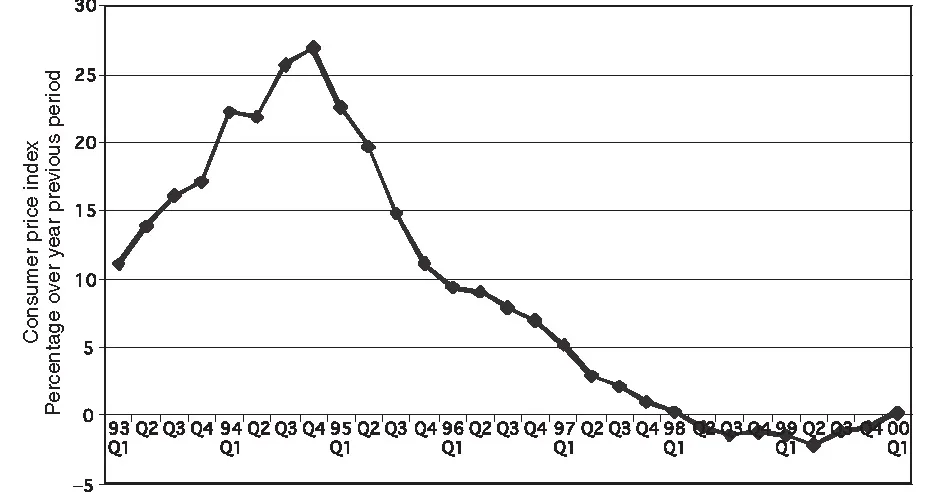

Public ownership restructuring began with central government policy initiatives. The foundation that made a serious programme of enterprise restructuring possible was laid by central government policy-makers soon after Zhu Rongji assumed effective control over economic policy in mid-1993. Two fundamental policy shifts were of enormous importance in creating the conditions for enterprise restructuring. First, Zhu Rongji presided over a fundamental shift in macroeconomic policy toward a much more conservative policy stance. Macroeconomic austerity gradually brought inflation under control. As Figure 1.1 shows, the effects were not immediate, and inflation peaked during 1994. Gradually, however, inflation came down and dropped below 10 per cent in the first quarter of 1996. During 1996 and 1997, policy-makers congratulated themselves on having engineered a ‘soft landing’, controlling inflation without harming economic growth. After the beginning of 1998, though, the economy slipped gradually into deflation, and prices fell throughout 1998 and 1999. Tough macroeconomic policies had become deeply entrenched in the economy. The success in controlling inflation was important for the subsequent enterprise restructuring in numerous ways. The ability to control growth of the money supply and credit shows that Zhu Rongji had at least temporary success in his efforts to reduce enterprise dependence on the banking system for cheap credit. A more ‘arm’s length’ relationship was created between state-owned banks and state-owned enterprises that made it much more difficult for failing enterprises to turn to the banking system for bail-outs. This was achieved partly just by throwing the weight of central government bargaining influence on the side of the banks, and partly by reorganizing the banking system in ways that made it less dependent on local government officials and local economic interests. Moreover, nominal interest rates – still administratively set by the government – were adjusted downward much more slowlythan the inflation rate dropped. As a result, real interest rates (nominal interest minus the actual inflation rate) turned positive at the beginning of 1996, and stayed significantly positive (over 5 per cent) after the beginning of 1997. Credit, in other words, became more difficult for state-owned firms to get, and much more expensive when it was available.

Figure 1.1 Consumer price inflation.

The secondary effects of macroeconomic austerity were, if anything, even more important. As growth slowed, competition became fierce. The falling price level after 1998 testifies to the intensity of competition and the abundance of supply. An enormous amount of industrial capacity had been created during 1992–96. Not only were domestic investment rates high, but a cumulative total of US$153 billion worth of foreign direct investment, mostly in manufacturing, flowed into China during those five years. As growth slowed, and much of this new industrial capacity came on stream, a fierce competitive environment developed. As numerous articles put it, China bid ‘farewell to the shortage economy, and hello to the buyer’s market’. Under these conditions, enterprises faced intensified competition on product markets, just at the time when their access to easy credit was being cut. Squeezed between two increasingly unforgiving forces, enterprises began to search intensively for solutions to their predicament.

The second overall central government policy initiative that made restructuring possible was a shift to a more rule-based approach to enterprise reform. The pace of economic legislation stepped up, but what was more significant was a government commitment to use ‘rule by law’ to impose a roughly equivalent set of economic obligations on most firms. Particularly during 1994–95, there were a number of important legislative milestones. First of the blocks was the tax reform implemented on 1 January 1994, which shifted government reliance to a broad-based value-added tax, and which also lowered and unified corporate profit tax rates. The tax reform had the effect of substantially (though not totally) equalizing tax rates among different businesses, and established the principle that different ownership systems should be subject to the same tax treatment. In addition to the new tax code, three important regulatory laws were passed in 1994–95 that shaped the environment for enterprise restructuring. The Banking System Law (1995) reinforced many of the ad hoc changes that Zhu Rongji had carried out in the previous years, strengthening the banking system’s independence and its ability to withstand (especially local) political pressures. The Company Law, also in 1995, provided an ownership and accounting framework that enabled all public enterprises to begin the process of reorganization, with clearly defined capital contributions, ownership, and executive bodies that represented the interest of the owners (shareholders). The third regulatory law, passed in 1994, was the Labour Law.2 The Labour Law had many important provisions, but the defining characteristic was the shift to compulsory universal labour contracts. The labour relationship henceforth was to be governed, in all cases, by a contract voluntarily signed by the employer and employee. By clear implication, the ‘iron rice bowl’ system of permanent employment was abolished, and an employment relationship of specified duration, which either side could dissolve at will, was created in its place.

The central government not only establishes the framework for economic policy, it also signals to local governments the scope for policy experimentationIn the case of enterprise restructuring the central government began to signal a permissive attitude as early as 1995. In April 1995, the State Council approved a report on ‘Re-employment Projects’ from the Ministry of Labour, creating a framework for local governments, enterprises and social welfare agencies to contribute resources to expanded training and job creation programmes.3 With this addition, by the end of 1995, the central government had in place a rough regulatory framework and a rudimentary social safety network. The social safety net, although full of holes, at least provided a framework for those local governments which had resources to provide help to unemployed and impoverished urban residents. Under construction since the mid-1980s, the social safety net included unemployment compensation, retirement funds independent of individual enterprises and, now, training and job creation programmes. With these elements in place, a framework – albeit fragile and rickety – was in place that could support an accelerated programme of enterprise restructuring.

Through 1996 and 1997 the official media gave increasingly prominent, positive coverage to localities that had carried out thorough enterprise restructuring. Particularly thorough coverage was given to the case of Zhucheng in Shandong, discussed further below. During the course of 1997, it became increasingly clear that the central government was allowing local governments enormous leeway in the pursuit of SOE restructuring. Moreover, beginning in early 1997, public discussions increasingly stressed the need for the private sector to pick up some of the slack created by public sector downsizing, and the need for a rapid growth in the ‘non-public’ economy.

The XVth Communist Party Congress in September 1997 marked a new peak of central government enthusiasm for restructuring. In his main report to the Congress, Jiang Zemin carefully chose a formulation describing ownership under the socialist market economy which subtly but unmistakably increased the role and legitimacy accorded to private ownership. Zhu Rongji emerged as Premier-designate at the Congress, and promoted a series of active policies designed to shrink and restructure the state sector. The dominant policy at the Congress was that of ‘grasping the large, and letting the small go’ (zhuada fangxiao). Under this formulation, central government organs would intensify the pace of managed restructuring of large state firms, while allowing small state and collective firms to be restructured by market forces. This Party Congress thus marked a major increase in the impetus given to restructuring, both by relaxing ideological constraints and by actively advancing central government support for a wide array of restructuring initiatives.

This level of enthusiasm for restructuring lasted through the National People’s Congress in March 1998. Zhu Rongji formally became Premier, and immediately announced a wide-ranging programme of accelerated change. Characteristically, he used the format of a nationally televised press conference, displaying his own authoritative position as well as his commitment to continued reforms, while keeping specifics to a minimum.4 Yet even as Zhu spoke, the central government policy emphasis was beginning to shift. With the Chinese economy continuing to slow and the Asian Crisis showing few signs of abating, Chinese leaders were becoming increasingly concerned about rising unemployment. Some signs of increased concern emerged at the Congress, and were incorporated into official policy in subsequent months, notably in a May 1998 special State Council meeting on unemployment and lay-offs.5

From that time through to the end of 1998, we saw a classic case of Chinese policy reformulation. While the central government repeatedly reaffirmed the original pronouncements on state enterprise, the emphasis of new proclamations clearly shifted. Stress was placed on t...