1 Introduction

Leighton Vaughan Williams

When I was asked to consider putting together an edited collection of readings on the theme of the ‘Economics of Gambling’, I was both excited and hesitant. I was excited because the field has grown so rapidly in recent years, and there is so much new material to draw upon. I was hesitant, however, because I knew that a book of this nature would not be truly satisfactory unless the papers included in it were new and hitherto unpublished.

The pressures of time on academics have perhaps never been greater, and it was with this reservation in mind that I set out on the task of encouraging some of the leading experts in their fields to contribute to this venture. In the event, I need not have worried. The camaraderie of academics working on the various aspects of gambling research is well known to those involved in the ‘magic’ circle, but the generosity of those whom I approached surpassed even my high expectations.

The result is a collection of readings which draws on expertise across the spectrum of gambling research, and across the global village. The papers are not only novel and original, but also set the subject within the existing framework of literature. As such, this book should serve as a valuable asset for those who are coming fresh to the subject, as well as for those who are more familiar with the subject matter. Topics covered include the efficiency of racetrack and sports betting markets, forecasting, lotteries, casinos, betting behaviour, as well as broad literature reviews. The twenty-nine contributors hail from nineteen academic institutions, as well as government service, from as far afield as the UK, USA, Australia, Canada, Israel and Ireland.

In many cases, the contributions would, in my opinion, have gone on to be published in top-ranked journals, but the authors lent their support instead to the idea of a single volume that would help promote this field of research to a wider audience. In all the cases, the authors have provided papers which are valuable and important, and which contribute something significant to the burgeoning growth of interest in this area. It has been a joy to edit this book, and my deepest gratitude goes to all involved.

Most of all, though, my thanks go to my wife, Julie, who continues to teach me that there is so much more to life than gambling.

2 The favourite–longshot bias and the Gabriel and Marsden anomaly: An explanation based on utility theory

Michael Cain, David Peel and David Law

Introduction

Research on gambling markets has focused on the discovery and explanation of anomalies that appear to be inconsistent with the efficient markets hypothesis; see Thaler and Ziemba (1988), Sauer (1998), and Vaughan Williams (1999) for comprehensive reviews of the salient literature.

The best-known anomaly in the literature on horse-race gambling is the so-called ‘favourite–longshot bias’, where the return to bets on favourites exceeds that on longshots. This was first identified by Griffith (1949), and confirmed in the overwhelming majority of later empirical studies; see below for some further discussion. A second apparent anomaly was reported by Gabriel and Marsden (1990 and 1991), who compared the returns to winning bets in the British pari-mutuel (Tote) market with those offered by bookmakers at starting prices. They reported the striking finding that Tote returns to winning bets during the 1978 British horse-racing season were higher, on average, than those offered by bookmakers; even though, they suggested, both betting systems involved similar risks and the payoffs were widely reported. Consequently, they suggested that the British racetrack betting market is not efficient. As noted by Sauer (1998) in his recent survey, the Gabriel and Marsden finding calls for explanation. That is one of the main purposes of this chapter.

We will show that the relationship between Tote returns and bookmaker returns is more complicated than implied in the Gabriel and Marsden study. Whilst Tote pay-outs are higher than bookmakers for longshots, this is not the case for more favoured horses; also see Blackburn and Peirson (1995) for additional evidence consistent with this point. In addition, we argue that bets on the Tote are fundamentally different from bets with bookmakers since the bettor is uncertain of the pay-out. Whilst bettors have some limited information on the pattern of on-course Tote betting via Tote boards, off-course bettors have no such information and the pay-out is determined by the total amount bet. If Tote bettors did have full information on pay-outs, then, the fact that the Tote paid out £2,100 on winning bets of £1 in the Johnnie Walker handicap race at Lingfield on 12 May 1978 whilst the bookmaker SP odds were only 16 to 1, would in itself invalidate the usual economists’ notions of arbitrage processes and market efficiency. Assuming, then, that the Tote pay-out is uncertain whilst bookmaker returns are essentially certain, expected returns will be equalised only if the representative punter is risk-neutral, an assumption implicit in Gabriel and Marsden, and in previous analyses of the relationship between Tote and bookmaker returns; see, for example, Cain et al. (2001). However, the assumption that the representative bettor is risk-neutral is not consistent with the stylised fact derived from empirical work on racetrack gambling, that there is a favourite–longshot bias; bets on longshots (low-probability bets), have low mean returns relative to bets on favourites, or high probability bets. This has been documented by numerous authors for both the UK (book-maker returns) and for the US pari-mutuel system (see, e.g., Weitzman, 1965; Dowie, 1976; Ali, 1977; Hausche et al., 1981 and Golec and Tamarkin, 1998). The standard explanation for this empirical finding has been that the representative punter is locally risk-loving; see, for example, Weitzman (1965) and Ali (1977). However, Golec and Tamarkin (1998) have recently shown for US pari-mutuel data that a cubic specification of the utility function, of the Friedman and Savage (1948) form, that admits all attitudes to risk over its range, provides a more parsimonious explanation of the data than a risk-loving power utility function with exponent greater than unity. We will show that, if the representative bettor is not everywhere risk-neutral, an explanation of both the observed relationship between Tote and bookmaker returns and the favourite–longshot bias can still be provided. This is the second main aim of the chapter.

Theoretical analysis

Utility and the favourite–longshot bias

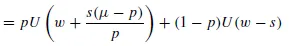

It is assumed that the representative bettor has utility function, U(⋅) and total wealth, w. With odds against winning of o and win probability, p, the expected pay-out to a unit bet is μ = p(1 + o) + (1 – p)0 = p(1 + o) and hence o = (μ/p) – 1 = (μ – p)/p. If the punter stakes an amount s, the expected utility of return is

E = E(U) = pU(w + so) + (1 – p)U(w – s)

The optimal stake for the punter is such that (əE/əs) = 0 and (ə2E/əs2) < 0 so that

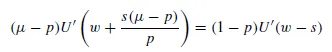

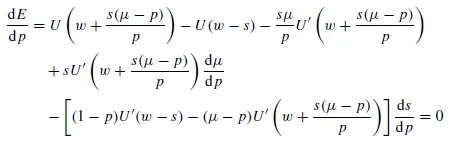

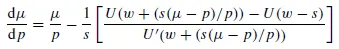

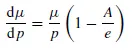

and s = S(μ, p; w){if E > U(w)}. Substituting s = s(μ, p) into equation (1) gives expected utility, E, as a function of μ and p, and hence we may obtain an indifference map in (μ, p) space. It is thus possible to differentiate equation (1) with respect to p and equate to zero in order to find the combinations of expected return, μ, and probability, p, between which the bettor is indifferent. This produces

and hence, in view of equation (2), equation (3) reduces to

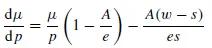

so that

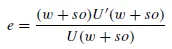

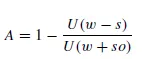

where

When w = 1 = s, the assumption made by Ali (1977) and Golec and Tamarkin (1998), equation (5) simplifies to

If U(0) = 0, then equation (6) reduces to

where e = e(X) = e(μ,/p) is the elasticity of U(⋅) at X = μ/p. Observe from equation (7) that the slope of the equilibrium expected return–probability frontier will be positive (or negative) depending on whether the elasticity is greater than (or less than) unity. Clearly, with a power utility function which is everywhere risk-loving, the (μ, p) frontier will be everywhere upward sloping – the traditional favourite–longshot bias.

A condition for the favourite–longshot bias is that (dμ/dp) > 0, in order that the mean return–probability relationship is not constant or declining throughout its range. It is perhaps surprising to find that this condition is consistent with a utility function that is not everywhere risk-loving over its range.

As an illustration, consider the utility functi...