14 Tonal relations

Lola L Cuddy

Department of Psychology, Queen’s University, Kingston, Canada

An important development for music perception and cognition in the last few decades is the flourishing interaction between experimental and music-theoretic approaches to systematic issues. According to Krumhansl (1995), the current psychological literature contains many and varied instances of the exchange urged in the 1950s in the writings of Meyer (1956) and Francès (1958/1988). Empirical studies of tonal relations, for example, have led to quantitative descriptions of listeners’ implicit knowledge of music-theoretic constructs; these descriptions portray the consistency and reliability of the internal representation of traditional tonal-harmonic structures. Moreover, and more recently, proposed theoretical structures for contemporary music have been subjected to experimental test, and the results have informed both analysis of psychological processes and critical evaluation of the theory. A particularly strong test of psychological proposals for music perception and cognition is offered when proposals are evaluated in the context of contemporary music (or composed excerpts with specially controlled properties).

In this chapter, I will provide an overview of the research issues engaged in our study of tonal relations (Cuddy, 1991, 1994), and will illustrate some connections between empirical results and music-theoretic constructs. I will first comment on the role of quantification and will illustrate research methods directed toward the quantification of the tonal hierarchy, taking the approach of Krumhansl and colleagues (Krumhansl, 1990). Next I will note convergence of the description of the tonal hierarchy that emerges from research findings with the description of stability conditions in Lerdahl’s (1988a, 1988b, 1989) extension of his tonal theory with Jackendoff (Lerdahl & Jackendoff, 1983). These considerations lead to questions about the constraints that are implied by the study of tonal relations within the Western tonal-harmonic system. I will then pursue the notion that principles of tonal relations, from both empirical and music-theoretic perspectives, may be applied to the study of listeners’ sensitivity to nontonal music structures.

QUANTIFICATION OF THE TONAL HIERARCHY

The study of tonality requires the analysis of complexity at many different levels, and is a challenge far beyond the scope of this chapter. I will deal primarily with elementary levels of description—the levels where the greatest control of experimental contexts can be obtained. This focus does not, however, mean that the findings are musically and psychologically trivial. On the contrary, the study of elementary levels conveys rich information about the delicate interface and interplay between the psychological processes of music perception and cognition. When musical elements as simple as scales and chord progressions engage a sense of tonality, we have evidence for many processes—the detection of raw acoustic attributes, detection of intervallic relationships, classification and categorisation, abstraction of a hierarchy of functions, and the application of knowledge. To illustrate: given the simple element C E G, a sense of the key of C depends on the input of sensory pitch information from the three sounded tones, the processing of relative information among the intervals formed by these tones, the detection of a tonal centre, C, from the pattern formed by the intervals, the assignment of function to the other tones sounded, and, finally, the assignment of function to tones not sounded. For example, once the key of C is established, our knowledge of tonal relations establishes the function of F even if F has not been sounded.

The above description is straight-forward, but detailed understanding of the nature, timing, and availability of the psychological processes engaged is not. To conduct research on these issues, a means of quantifying listeners’ sense of tonality is needed. With a quantitative approach, we can evaluate listeners’ sensitivity under different conditions, and examine how sensitivity changes with relationship to factors such as musical context, attention, learning, age, experience, and culture. Quantification provides a tool for testing the predictions of various theoretical formulations.

An important methodological contribution to the issue of quantification, called the probe-tone technique, was initiated in the late 1970’s by C. L Krumhansl and R.N.Shepard (see Krumhansl & Shepard, 1979); subsequent developments are summarised in Krumhansl (1990). Two versions have been constructed, the single-probe and the double-probe technique. In the singleprobe technique, a listener is presented with a musical context followed by a probe tone, one of the 12 tones of the chromatic scale. In a typical paradigm, the listener is asked to rate how well the probe tone fits the context in a musical sense. The set of 12 probe-tone ratings for a context is called the probe-tone profile for that context. In the double-probe technique, the listener is presented with a musical context followed by two probe tones, a pair of tones selected from the 12 tones of the chromatic scale. The listener is asked to judge the musical relationship, or similarity of function, of the first tone to the second tone, given the context.

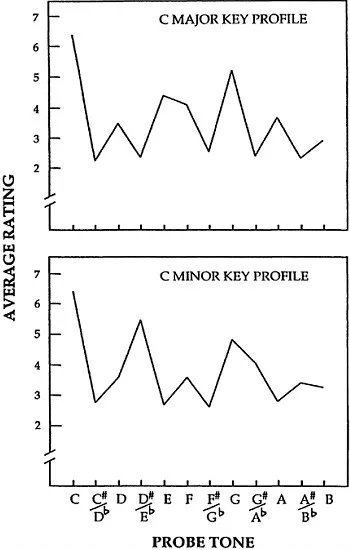

Figure 14.1 displays standardised probe-tone profiles, collected by the single-probe technique, for the keys of C major and C minor (Krumhansl & Kessler, 1982). Profiles were obtained for contexts consisting of tonic triads, and chord cadences, and then averaged to form the standardised profiles shown in Fig. 14.1. The averaging of profiles is an important point to note; the standardised profiles are not intended to reflect local variation dependent on specific context, but, rather, reflect the overall regularity contained in profiles obtained from key-defining contexts. Thus, they provide a standard against which specific profiles, obtained in specific cases, can be compared.

Inspection of Fig. 14.1 reveals that the standardised profiles capture the hierarchy of function described by traditional music theory: the tonic receives the highest rating, followed by the other tones of the tonic triad, followed by the other scale tones, followed, finally, by the tones outside the scale.

The reliability and validity of tonal hierarchy measures collected by the probe-tone technique have been repeatedly demonstrated in our laboratory and elsewhere. One example is research conducted in collaboration with Willi Steinke (Steinke, Cuddy, & Holden, 1993; Steinke, Cuddy, & Peretz, 1994). Probe-tone ratings for musical contexts consisting of cadences in both the major and minor keys and a tonal melody in the major key were collected from a large sample of participants (n=100) over a wide range of age, formal education, and music training. Reliability was demonstrated in the finding that the ratings for all contexts reflected the levels of the tonal hierarchy recovered in the standardised profiles.

Moreover, validity was demonstrated in the finding that participants’ abilities to produce the levels of the tonal hierarchy in the probe-tone profiles were intercorrelated with other tests of sensitivity to tonal relations. These other tests included judgement of melodic endings, discrimination of tonal from atonal melodies, and discrimination of tonally conventional from nonconventional chord progressions. All tests involved ranking the most to least tonal stimulus along a continuum of tonality. Further analyses revealed that the intercorrelations could not be completely explained in terms of amount of musical training or in terms of performance on intelligence measures or other nonmusic tests of cognitive ability (e.g. standardised tests of abstraction, vocabulary, and memory). At Liège, we reported the results of factor analyses and model testing of these data (Steinke, Cuddy, & Peretz, 1994). A principle-components analysis revealed a dissociation between the music tests and the nonmusic tests; music tests loaded on one factor and the nonmusic tests on a second factor. Model testing ruled out alternative solutions, including dissociation between abstraction vs nonabstraction tests, auditory vs nonauditory tests and linguistic vs nonlinguistic tests.

In addition, we reported the data from a neurologically impaired individual, CN, who had a history of bilateral temporal-lobe surgery. CN had been classified as amusic but not aphasic (Peretz & Kolinsky, 1993). Compared to controls matched for age, gender, formal education and musical background, CN scored much lower on the music tests, but scored much the same on the nonmusic tests. Her data were consistent with the notion that there is functional specificity for certain music abilities; in the present instance there was a specific loss of tonal encoding of musical pitch.

Another validation of the tonal hierarchy measure recovered by the probetone technique has been obtained from studies of sensitivity to key shifts or modulations in a musical passage. Krumhansl and Kessler (1982) constructed chord sequences in which the type of modulation contained in each sequence was derived from Piston’s (1987) table of harmonic progressions. Probe-tone profiles were collected for each successive chord in each sequence. The findings outline how a sense of the first key of the sequence becomes established and then changes, over time, to a sense of the second key. Comparison of the findings for the different modulation types (e.g. near vs distant) were interpretable in terms of music-theoretic expectations, and also informed psychological descriptions of the unfolding processes tracking key movement in time.

Bill Thompson and I have pursued the application of probe-tone techniques to track the shifting sense of key in excerpts from Bach chorales (Cuddy & Thompson, 1992). More recently, we have been studying listeners’ sensitivity to modulations in harmonised sequences based on melodies composed by Hindemith (1968). In the course of this work, we have been analysing the performance expression for the sequences provided by an expert pianist (Thompson & Cuddy, 1994, in press), and we presented some of these data at Liège. Judgements of key movement were obtained for harmonised sequences presented without performance expression in one experiment, and with performance expression provided by the pianist in a second experiment. Sequences contained modulations of either 0, 2, 4 or 6 steps around the cycle of fifths. When performance expression was provided, judgements of key movement conformed more closely to predictions based on models of keyrelatedness (Krumhansl & Kessler, 1982) than when performance expression was absent.

FIG. 14.1. Standardised probe-tone profiles for the keys of C major and C minor. From Tracing the dynamic changes in perceived tonal organization in a spatial representation of musical keys by C.L.Krumhansl and E.J.Kessler, 1982, Psychological Review, 89, p.

343. Copyright 1982 by the American Psychological Association.

Redrawn with permission.

Next we examined the expressive variations introduced by the pianist (coded as MIDI data) and compared the variations with the values of the standardised profiles for the keys of the sequences. This comparison revealed that the pianists’s variations in loudness and timing were correlated with the tonal hierarchies of the keys of the sequences. Notes that were tonally stable within a key tended to be played for longer duration in the soprano and bass voices, and softer in the bass voice. The performance thus contained cues about tonal hierarchies that may have influenced listeners’ judgements of key and key movement.

...