- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This volume has as its focus the role of the Marshall Plan as both a force in the transformation of European Economic practices and a stimulus to political integration in Europe. This organizing theme is framed in terms of two other issues that are central to contemporary debates in international political economy and geopolitical studies: the origins and development of the Cold War, and the growing globalisation of the world economy. In relating the Marshall Plan to these issues, this book goes beyond the typical diplomatic history approach to place the Plan in the context of both the political economy of late twentieth-century Europe, and the impact of American models of business and government that came with the Plan.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Marshall Plan Today by John Agnew,J. Nicholas Entrikin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economics & International Economics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part 1

European Recovery

1

Post-World War II western European Exceptionalism: The Economic Dimension

Introduction

After World War II western Europe developed a set of politico-socio-economic institutions that turned out to work remarkably well. The institutional setup was scorned by the Left as a social democratic halfway house that failed to solve the structural contradictions of capitalism and was doomed to eventual instability and collapse. Similarly, the Right saw it as sapping the will and individualistic enterprise of the people, and thus opening the door to left-wing totalitarianism. But the western European social democratic ‘mixed economy’ worked amazingly, remarkably, unbelievably well. It delivered economic growth at a pace that the world had never before seen. It produced an after-tax and transfer distribution of income that was remarkably egalitarian. It powered western Europe’s remarkably smooth and rapid transition through the final stages of its structural transformation to an industrial economy and society.

So what went right? Where did this post-World War II western European exceptionalism come from? What lessons were learned from the Great Depression and from World War II, and why did these lessons prove so appropriate for managing western European economies in the first generation after the war?

And what went wrong thereafter? The post-World War II European miracle lasted for only a single generation, until 1973. Why was western European exceptionalism so temporary? And why did the economic policy lessons learned from the Great Depression, World War II, and the first post-World War II generation turn out to be inappropriate for the post-1973 period?

The short answer is that after World War II western European politico-economic policy was successful because it tapped into a virtuous circle. Trade expansion drove growth, growth drove expanded social insurance programs and real wage levels; expanded social insurance states and real wage levels made for social peace, which allowed inflation to stay low even as output expanded rapidly; rapidly expanding output in turn led to high investment, which further increased growth and created the preconditions for further expansions of international trade.

The combination of all these factors created an extra 1.5–2 percent per year of productivity growth – the approximate magnitude of the unexpectedly rapid growth of the post-World War II western European miracle – coming from nothing but the fact that things had started off on the right foot.

Why, then, did the period of western European exceptionalism end?

I believe that western European exceptionalism ended because it was assassinated. It was assassinated by an odd combination of oil barons, union leaders and monetarists. Without the tripling of world oil prices in 1973, and again in 1979, the pressure to do something to reduce inflation would have been much weaker. It was strong pressure to do something to reduce inflation that broke down the alliance between social democratic welfare state politicians and union leaders. The former pressured the latter to sacrifice their real wages in support of the fight against inflation. This they refused to do. The consequence was, first, higher inflation and, second, a shift in political power to the Right and the turnover of power to make monetary policy to central banks interested in halting inflation no matter what the cost.

Once it was plain that the old consensus politicians could not fight inflation through corporatist dialogue, the new non-consensus politicians won votes by promising that they would fight inflation through monetary restraint – and their monetarist economic advisers assured them that any excess unemployment created by fighting inflation would be transitory and temporary (see Friedman, 1968). In the United States the monetarists turned out to be largely right: the higher unemployment created by fighting inflation turned out to be transitory and temporary. In Europe the monetarists turned out to be wrong: the higher unemployment created by fighting inflation turned out to be persistent and permanent, leaving Europe with its current problems of structural unemployment (see Cohen, 1996).

The post-World War II western European Miracle

The Magnitude of the Miracle

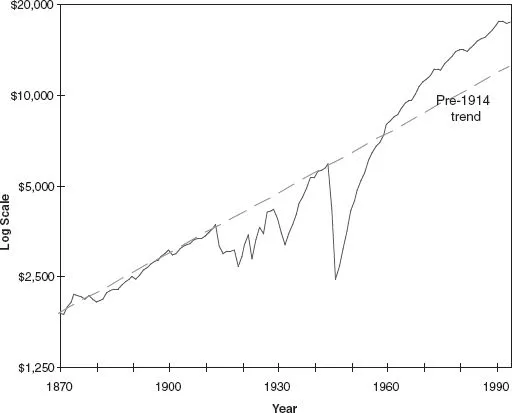

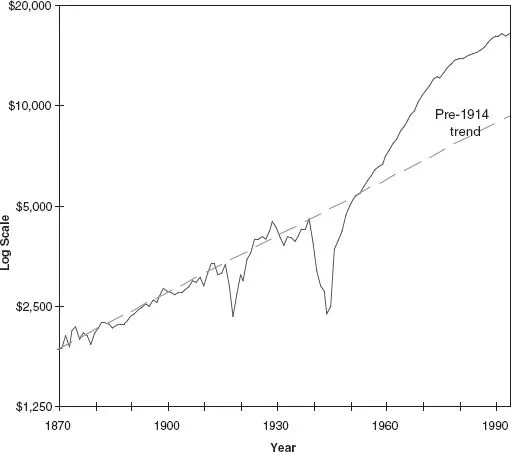

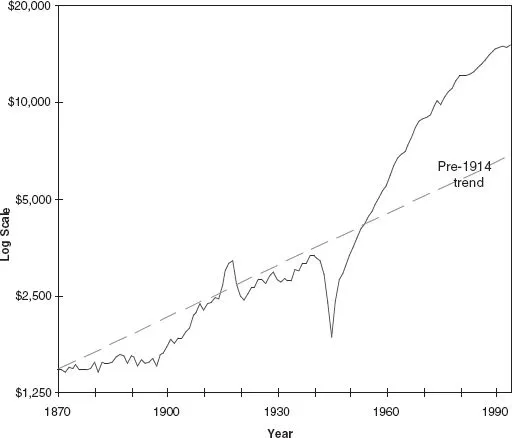

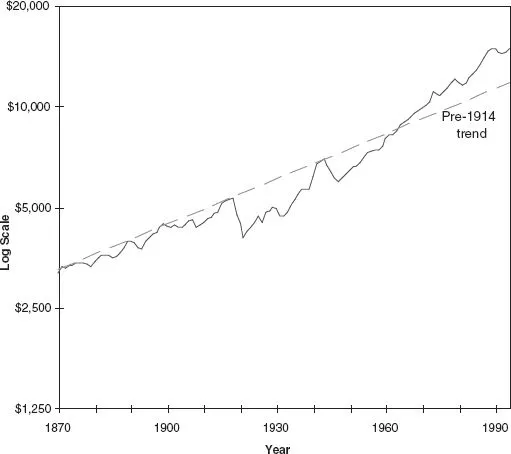

Nobody disputes that post-World War II western European economic growth was miraculous. The magnitude of the miracle is clear in the graphs of the broadest of macroeconomic aggregates. As Figures 1.1–1.4 show, in West Germany, France, Italy, and even in Britain, the level of real economic product – GDP – per capita exceeded the best performance of the interwar period by the early 1950s. By 1960 all countries’ economic product was higher than not just the best interwar performance, but it was well above levels that would have been predicted by extrapolating pre-1939 or pre-1914 trends into the indefinite future.

Figure 1.1 Germany (West after 1945): GDP per capita, 1870–1994

For example, in West Germany just after reunification, GDP per capita (measured in 1990 dollars) from the late 1970s through the 1990s was, and remained, some 40 percent higher than even pre-1914 trends would have predicted, and some 70 percent higher than would have been predicted from the interwar growth trend.

In France GDP per capita settled into a new trend some 70 percent higher than the pre-1914 trend – and fully 100 percent higher than the interwar trend. Italy was even more extreme, with GDP per capita levels settling into a new trend at double what would have been predicted from simple extrapolation from before 1914 or from the relatively stagnant interwar period. Even Britain – which experienced the smallest relative acceleration in growth after World War II of the four – has today a GDP per capita level some 20 to 30 percent above the pre-1914 trend, and some 30 to 40 percent above the interwar trend. The net result has been to give the average Italian in the 1990s a measured material standard of living of some $16,500 dollars of 1990 purchasing power – more than five times the measured material standard of living on the eve of the Great Depression. For (West) Germany the coefficient of multiplication is 4.5; for France it is 3.5; for Britain the coefficient of multiplication is roughly 3.

Figure 1.2 France: GDP per capita, 1870–1994

National statistical agencies, however, are far from perfect. They have a hard time measuring the impact on the material standard of living of the invention of new goods and new types of goods. Walk around Westwood, Los Angeles, and see the people wearing polarized sunglasses, listening through earphones to portable CD players, wearing shoes with well-cushioned yet lightweight soles, and drinking the products of espresso machines. Ask yourself the question: when did the increment to material welfare from the ability to make shoes with better soles, polarized sunglasses, or espresso machines enter into national income accountants’ calculations of aggregate economic activity? The odds are that each of these improvements never made it into national income accountants’ estimates of long-run growth. National income accountants have limited budgets and very difficult tasks.

Figure 1.3 Italy: GDP per capita, 1870–1994

There are many who believe that unmeasured improvements in productivity stemming from new goods and new types of goods average perhaps 1 percent per year today. It seems reasonable to extrapolate their estimate to cover all of this century, and to hypothesize that unmeasured improvements contributed perhaps half as much in the second half of the nineteenth century, when technological progress was slower. Before 1850 these issues are much less important, for most of pre-1850 waves of innovation were in the making of producer, not consumer, goods. If correct, then the coefficient of multiplication since 1930 in Italy is not a factor of 5 but a factor of 10; in (West) Germany not a factor of 4.5 but a factor of 9; in France not a factor of 3.5 but a factor of 7; for Britain not a factor of 3 but a factor of 6. That is, I think, the proper measure of the post-World War II western European miracle.

Figure 1.4 Britain: GDP per capita, 1870–1994

Does this seem too large a coefficient of multiplication? It probably is if you are one of relatively poor for whom the inventions of the past 60 years are a smaller part of your consumption bundle. It probably is too large if you are one of the very rich for whom the principal benefit of wealth is, as economist Paul Krugman likes to say at conferences, ordering people around: ‘seeing ’em jump’. It probably is too large if you follow Richard Easterlin (1997) and believe that increased material wealth does not increase human happiness, and that our restless dissatisfaction and non-satiation today tells us that the twentieth century has seen the triumph of economic growth. Easterlin adds that this triumph is not a triumph of humanity over material wants. Instead, it is material wants that have triumphed over humanity.

But for those from the lower middle class to the merely rich, it is hard to imagine anyone who does not view their material welfare as vastly, vastly greater than that of their counterparts of 60 years ago. Consider modern audiovisual and recording technologies, antibiotics, information-processing, telecommunications and transportation. It is hard to escape the conclusion that more than half the differences between 1300 and today in how western Europeans live their material lives have come since the start of the Great Depression.

Was This Miracle Inevitable?

From today’s perspective it is easy to ignore claims that the western European growth miracle is something in need of special explanation. Is not the ‘convergence’ of western European economies to the approximate level of national product per capita and the approximate long-run growth path of the United States a ‘natural’ process? Was it not bound to happen as technology diffused across national boundaries, as universal secondary education made its presence felt, and as governments allowed market forces to direct investment and to weed out noncompetitive firms (see Barro and Sala-i-Martin, 1995)?

But there is nothing ‘natural’ about such ‘convergence’ to North American norms. To put it another way, if ‘convergence’ is ‘natural’ to economists, it is ‘unnatural’ to political economists. There are many forces and factors that could have blocked the western European growth miracle – and that did indeed block its analogue in many times and places.

There are only only two other places and times that this ‘natural’ process has been operating with strength similar to that of western Europe in the first post-World War II generation. One is North America during its 1860–1950 century of industrialization. A second is East Asia in the past two generations. But in the world as a whole since 1870, and in the world since 1945, the dominant trend has been toward divergence, not convergence (see DeLong, 1988). Over the past century, at least, those nations and economies that start behind in GDP per capita have tended to fall further behind as time has passed.

Let me expand on this point by very briefly sketching out crude pictures of three counterfactual alternative futures for western Europe as of 1945 – alternatives that might have been the future, or that informed observers in 1945 thought might well become the future, but that were vastly different from what western Europe’s actual experience turned out to be: relatively stable democracy, growing welfare states with diminishing income inequality and rapid economic growth.

Stalin’s Dream

The first we might as well call Stalin’s dream: the future that Josef Stalin may well have expected to see in western Europe in the generation after the end of World War II. Or, more accurately, a future that we might speculate Stalin expected, for trying to read the mind of Josef Stalin is an extremely hazardous occupation. For Stalin and his acolytes, all the experience of the interwar period reinforced the interpretation that Lenin (1916), drawing from Hobson (1913), had arrived at in trying to understand the failure of Marx’s (1848) predictions of increasing immiserization to come true in the pre-World War I period. The pre-World War I economies had managed to avoid the problems of overproduction, insufficient consumption and consequent financial crises, deep depressions and worker immiserization through imperialism: maintaining employment at home by force-flooding the rest of the world with exports. But by 1910 there were no new markets to conquer: imperialist expansion had reached its limits.

Hence, Stalin and his acolytes may well have believed that history was on their side. In World War I the imperialist capitalist powers resorted to armed struggle so that the victors, at least, could restore the conditions for imperial expansion and further prosperity. But the spoils of empire from defeated Germany, Austria-Hungary and Turkey were small. Hence the post-World War I prosperity in the victors was short-lived and anemic. Moreover, the bourgeoisie in the losing nations became anxious for a rematch – World War II.

World War I had brought their brand of state socialism to Russia and its dependencies. World War II had brought their brand of state socialism to the Balkans, to the Elbe and to half of Asia. So to Stalin and his acolytes the obvious thing to do in the aftermat...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of illustrations

- Contributors

- Foreword: The Marshall Plan Speech

- Preface

- List of Abbreviations

- Introduction: The Marshall Plan as Model and Metaphor

- Part I: European Recovery

- Part II: Markets and National Policy

- Part III: International Cooperation and Globalization

- Index