- 488 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Connectionist Models in Cognitive Psychology

About this book

Connectionist Models in Cognitive Psychology is a state-of-the-art review of neural network modelling in core areas of cognitive psychology including: memory and learning, language (written and spoken), cognitive development, cognitive control, attention and action. The chapters discuss neural network models in a clear and accessible style, with an emphasis on the relationship between the models and relevant experimental data drawn from experimental psychology, neuropsychology and cognitive neuroscience. These lucid high-level contributions will serve as introductory articles for postgraduates and researchers whilst being of great use to undergraduates with an interest in the area of connectionist modelling.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Connectionist Models in Cognitive Psychology by George Houghton in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Cognitive Psychology & Cognition. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

Introduction to connectionist models in cognitive psychology: Basic structures, processes, and algorithms

George Houghton

University of Wales, Bangor, UK

INTRODUCTION

This book aims to present an overview of the current state of connectionist modelling in cognitive psychology, covering a broad range of areas. All of the authors are specialists in their chosen topic, and most have been actively engaged in connectionist cognitive modelling for many years. In these chapters the reader will find numerous examples of the way in which theories implemented in the form of connectionist models have interacted, and continue to interact, with experimental data in an intellectually productive and stimulating way. I believe these contributions speak for themselves and that there is no need in this introduction to advance or defend any particular conception of the modelling enterprise. Instead, my purpose here is to provide an accessible introduction to some of the basic, and most frequently encountered, features of connectionist cognitive modelling, ones that recur throughout the chapters of the book. Readers new to connectionist modelling, or who encounter difficulty with technicalities in any of the chapters, will hopefully find the discussion presented here of some use.

The development of connectionist (or “neural network”) models has a long history, involving contributions from scholars in many disciplines, including mathematics, logic, computer science, electronic engineering, as well as neuroscience and psychology. For instance, the ideas of Donald Hebb on modifiable connections go back at least to the 1940s; the “delta rule” learning algorithm discussed below dates to the early 1960s (Widrow & Hoff, 1960). However, despite influential work by such authors as Grossberg (1980), Kohonen (1984) and others, the impact of such ideas on cognitive psychology really began with the publication in 1986 of the two volumes by Rumelhart, McClelland and colleagues (Rumelhart & McClelland, 1986; McClelland & Rumelhart, 1986). These books, as well as describing numerous connectionist models and algorithms, including the well-known back-propagation learning rule, also contained programmatic chapters written with an “ideological” purpose. The authors clearly believed they were on to something new and exciting, something that would change the way theoretical cognitive psychology was done, and they wanted the rest of us to know about it.

Previously, during the 1970s and early 1980s, modelling in cognitive psychology was dominated by the idea, initially inspired by developments in linguistics and artificial intelligence, that all cognitive processes involved the rule-based manipulation of cognitive symbols (Charniak & McDermott, 1985). On this account, the dominant metaphor for the relationship between the brain and cognition was that of the hardware/software division of computing. The brain is the hardware (the physical machine) and the cognitive processes are the software (programs) being run on the machine. The crucial thing about this metaphor is that understanding how a piece of software works (i.e. understanding the rules of the program by which one can predict its behaviour) does not require knowledge of the machine it is running on. Indeed, the same program can run on very different physical machines, so long as each machine has a compiler for the program. Hence, an understanding of the program (predicting its behaviour) will be independent of the machine. It is a simple step from this view to the idea that the “rules” of cognition (our mental software) should be stated at an abstract, functional level, without reference to physical machine properties (Pylyshyn, 1984).

Neural network modelling involves a shift in this view, proposing rather that there is no such clear division in real brains: the way the brain physically operates will need to be taken into account to explain cognitive phenomena. To take one example, many phenomena in learning and memory can be accounted for by network models of associative learning, in which links are formed between “neurons” representing different aspects of the environment (see Shanks, Chapter 2; Kruschke, Chapter 4; O’Reilly, Chapter 5, this volume). In connectionist networks, this is not an accident; that is, it is not just one form of memory out of many that could be equally easily implemented. Associative memory is therefore “natural” to neural network models. At the same time, most current work on the neural basis of memory is dedicated to understanding how synaptic connections between neurons can be modified. It is hard to overestimate the importance of this coming together of the cognitive and neuroscientific levels of investigation; although scientists in each field will have their own specific issues, which may not easily translate into the terms of the other, there is nevertheless a central, common perspective (in this case, memory is in the connections) which is meaningful to both fields, and which allows the productive interchange of discoveries and questions. The theoretical “lingua franca” in which this interdisciplinary discourse takes place is that of connectionist networks.

Hence, the success of the connectionist program in cognitive psychology has not just been due to the empirical success of individual models. The push for a more “neurally-inspired” form of modelling came at the right time. By the mid-1980s the work of the cognitive neuropsychologists, investigating the patterns of breakdown in cognitive capacities as a result of brain injury, had become a major force in cognitive psychology (Shallice, 1988). This work not only led to revisions of traditional “box-and-arrow” models of cognitive architectures, but also produced a demand for computationally explicit models that could be artificially “damaged”, while continuing to function at a suboptimal level (Bullinaria, Chapter 3, this volume). The disturbed behaviour of the model following various patterns of damage could then be compared to the behaviour of individual patients (Shallice, Glasspool, & Houghton, 1995). The symbolic approach to cognition was singularly unhelpful in this enterprise, as models based on it tend to either work perfectly (i.e. as programmed) or to crash, generating only error messages. Generating a damaged version of such a model, if it is feasible at all, typically involves extensive reprogramming to implement the hypothetical effects of the brain damage. For example, if the model involves the interaction of separate modules, then any disruption in the output of one module (the damaged one) will generally require reprogramming of any other modules receiving that output. If this output is not of the form expected, then it will cause the program to crash. Connectionist models, on the other hand, lend themselves easily to forms of damage: for instance, by the addition of random noise to weights or activations, loss or reduction of connections, and so forth. The models will always continue to function under such circumstances, but the patterns of breakdown will not be random.

THE NEURAL BASIS OF CONNECTIONIST MODELS

Connectionist models of cognitive functions are said to be “neurally inspired”. However, it is fairly rare to come across models containing features specifically based on data regarding the brain mechanisms involved in the particular capacity being modelled. In most cases this is simply because nothing very specific is known about these mechanisms. Of course, in many cases a given psychological function can be reliably located within a circumscribed brain region, generally some part of the cerebral cortex in the case of higher perceptual and cognitive functions. However, this kind of simple localization (achieved by studies of the performance of brain-injured patients, and functional neuroimaging) does not provide much in the way of constraints on the mechanisms built in to the models. The simple fact is that we do not yet understand how specific cortical neural circuits work, or how to constrain functional principles on the basis of the kind of variation in cortical architecture that underlies brain maps of such as the classic Brodmann map.

Connectionist models are therefore neurally inspired in a more general sense. They are based on a set of widely held beliefs about what are the central functional characteristics of the way in which neurons represent, store, and retrieve information to construct our behaviour. These basic characteristics should not be thought of as being complete, or even undeniably correct. However, it is necessary to start somewhere, and current work has shown that very interesting and empirically successful models can be constructed using a handful of basic ideas.

Below I discuss the most common of these features, ones that appear repeatedly in the articles in this book. I hasten to add that the following is not intended to constitute an introduction to the basic principles of neuroscience, but simply to highlight the neural origins of the features most commonly found in connectionist models in cognitive psychology.

The neuron

The fundamental principle of neuroscience is the so-called “neuron doctrine”, the first complete expression of which is typically attributed to the Spanish histologist Santiago Ramon y Cajal, in work published 1888–1991 (Shepherd, 1992). At the time, it was widely supposed that the nervous system was a single continuous network, the “reticular theory”. Ramon y Cajal used microscopes to view nervous tissue stained by a method invented about 14 years earlier by the Italian physician Camillo Golgi, and recorded what he saw in hundreds of detailed drawing. These observations showed (to Ramon y Cajal, at least) networks made up of distinct cellular elements, typically containing a bulbous body; short, branching filaments (the dendrites); and a single elongated projection (the axon). The neuron doctrine thus states that the nervous system is composed of physically separate entities (neurons), and hence that understanding how the nervous system works requires an understanding of the neuron.

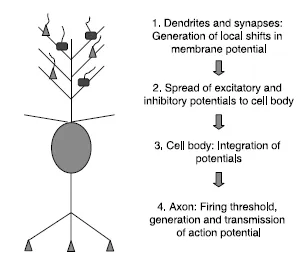

The neuron is an electrochemically excitable cell capable of sending spatially localized, invariant impulses (action potentials, discussed further below) throughout the brain and body. The prototypical (projection) neuron (Fig. 1.1) is comprised of: a cell body (soma) containing the cell nucleus; a set of branching elements emanating from the soma, known as dendrites, which act as input sites for connections from other neurons; and a single pronounced projection, the axon, which makes distant connections to other cells. The dendrites and cell body are the main “input sites” of the neuron, where connections from other neurons are made. The axon carries signals from the neuron to other cells, hence acting as an output channel. Although neurons have at most one axon, the axon can branch many times, allowing a single neuron to make contact with many others.

Figure 1.1. An idealized neuron based on the pyramidal cell of the cerebral cortex. The function of the neuron is shown as transforming mixtures of excitatory and inhibitory dendritic potentials into the production of action potentials with a given firing rate. In real pyramidal cells, the cell body of the neuron also receives (mostly inhibitory) synapses.

How are these contacts between cells made? At the time of the formulation of the neuron doctrine this was not known, and it was not until as late as the 1950s that the theory of the chemical synapse, the most common type of connection throughout the nervous system, became firmly established. Synapses are mainly formed between the axon terminals of one neuron (the pre-synaptic neuron) and the surface of the dendrites and cell bodies of others (post-synaptic neuron). Between the pre- and post-synaptic elements there is a small gap, the synaptic cleft. How communication between neurons takes place at synapses is discussed below.

This description of the neuron is fairly generic and best characterizes long-axon, projection neurons, which send signals between brain regions, and between the brain and the peripheral nervous system and spinal cord. However, the nervous system contains many variations on this theme, reflecting specialization of function. For instance, the Purkinje neuron of the cerebellum has an enormous system of dendrites, which appears to be needed to accommodate as many as 200,000 synapses (Llinas & Walton, 1990). All brain regions contain intrinsic or local-circuit neurons, which do not send signals out of their containing region, and hence have only relatively short axons. The distinction between this latter type of cell and projection neurons (which send long axons between nervous system structures) is an important one. The projection neurons of any brain structure are often referred to as its principal neurons. Since these are the only neurons that leave a given area, they are the route by which the results of any “computations” carried out within the region are conveyed to other brain structures, or to the muscles. Since the only thing projection neurons appear to do is to produce action potentials (see below), it follows that the results of any significant kind of neural computation must eventually be coded in the firing pattern of these neurons. Of particular interest to cognitive psychology, the principal cell of the cerebral cortex is the pyramidal cell, which constitutes about 70% of all cortical cells. Moreover, the major input to any cortical region comes from other cortical regions, i.e. from cortical pyramidal cells (Douglas & Martin, 1990), and connections between cortical regions are usually reciprocal. This is true even of primary sensory regions (such as primary visual cortex, V1), and presumably indicates the importance of “top-down”, or feedback, projections on even supposedly “low-level” sensory processing. A fair generalization, then, is that the “language” of the cerebral cortex, by which cortical areas talk to each other, and to other parts of the brain, is expressed in the firing patterns of pyramidal cells.

The action potential

The first nervous systems evolved in the sea, in water full of salts such as potassium and sodium chloride. Dissolved in water, the constituents of these salts separate into positively and negatively charged ions, and the cells of ancient sea creatures evolved to exploit these ions to create the local electrical potentials which underlie all neural activity. Although we have long since left the sea, in effect we continue to carry it around with us in the fluid which surrounds and permeates the neurons in the brain. The membrane of the neuron contains mechanisms which ensure that the positive and negative ions are unevenly distributed inside and outside of the cell, so that in its resting state a neuron has a net internal negative charge (of about −70 millivolts, the resting potential). This polarization leads to pressure on positive sodium ions in the extracellular fluid to enter the cell, which they can do so via specialized channels in the cell membrane. However, in a beautiful piece of natural engineering, whether the relevant channels are open or closed depends on the potential across the cell membrane, and at the resting potential the sodium channels are closed. However, at a slightly less negative potential, called the “firing threshold”, the channels open, allowing positive charge, in the form of sodium ions, to enter the cell. Whenever this happens, there is a local “depolarization” of the neuron, as the potential turns from negative to positive. If the firing threshold is crossed at the initial part of the axon, t...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- List of contributors

- Series preface

- Chapter One

- Section One: Learning

- Section Two: Memory

- Section Three: Attention and cognitive control

- Section Four: Language processes