- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

War and Peace in the Baltic, 1560-1790

About this book

From the middle of the sixteenth century to the end of the eighteenth cetury the Baltic sea was the scene of frequent conflicts between the powers that surrounded it. As the fortunes in the struggle changed, so did the composition of opposing alliances and the identity of the leading participants. Not only were the littoral states concerned by the outcome; other European states were anxious thoughout the period with what went on in the Baltic, where the emergence of one dominant power could be potentially dangerous and where many had important commercial interests. Stewart Oakley makes clear the causes and course of the conflicts and explains the varying fortunes of the participants. It traces the emergence of Sweden, poor as it was in resources, as the leading power in the area in the early seventeenth century, the early unsuccessful attempts by the Muscovite state to break through to the Sea, the eventual collapse of Sweden's `empire' at the beginning of the eighteenth century and final emergence of Russia as the leading player on the stage. The main part of the work ends with the failure of Sweden's final attempt to regain something of its former status. The subsequent fortunes of the area are described briefly.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

SETTING THE SCENE

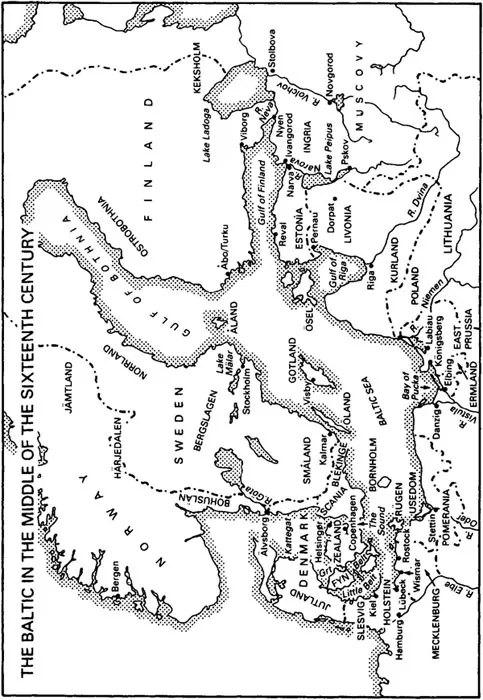

The Baltic, like the much larger Mediterranean,1 of which it is in many ways northern Europe’s equivalent,2 is almost an inland sea. Access to the world’s oceans is provided only by three narrow outlets: the Sound between the most easterly and largest Danish island of Zealand (Sjælland) and the southernmost part of the west coast of what is now Sweden, only 5 km wide at its northern end; the Great Belt between Zealand and the second largest Danish island of Fyn;3 and the Little Belt between Fyn and the Danish mainland (Jutland or Jylland). The Mediterranean is divided into western and eastern basins between Sicily and Tunisia. The Baltic is similarly divided into two well-defined main areas: a larger southern basin between the Danish islands and the coasts of ‘Balticum’;4 and a smaller northern arm—the Gulf of Bothnia. These are separated from each other by an almost continuous string of islands between the Swedish capital of Stockholm and the ancient Finnish capital of Turku (Åbo),5 of which the Åland islands (now Finnish) form the central core.

The struggle for power in the Baltic in the early modern period, which will be examined in the succeeding chapters, was in effect a struggle for power in the southern Baltic, which takes up well over half its total area.6 Around this lie the most densely populated land, the main ports of the region and the most productive agricultural areas. But, as will be seen, for long periods the struggle centred even more narrowly on the Baltic’s eastern inlet of the Gulf of Finland, at the extreme eastern end of which Tsar Peter I (the Great) of Russia founded at the beginning of the eighteenth century his new capital of St Petersburg to be his ‘window on the west’.

In the middle of the southern Baltic basin lies the Sea’s largest island of Gotland. By the sixteenth century this had lost its earlier importance as a commercial centre for trade between eastern and western Europe, but it was still of considerable strategic significance, lying as it does close to the main channels of communication by sea between central Sweden and the north coast of Germany. Of the other Baltic islands, that of Öland, lying like a long cigar off the east coast of Sweden south-west of Gotland and sheltering the port of Kalmar, has played only a minor role in the region’s history, but those of Ösel (Saaremaa), which blocks access to the Gulf of Riga and the mouth of the River Dvina (Düna), of Bornholm between the north German coast and southern Sweden, and of Rügen and Usedom at the mouth of the river Oder in Pomerania have all been the subject of dispute because of their value as bases.

The main rivers flowing northward or north-westward into the Baltic from the heart of the European landmass have provided access to a large and potentially rich hinterland.7 The Oder, Vistula (Wisla) and Dvina each has at or near its mouth an important port, respectively Stettin (Szczecin), Danzig (Gdask) and Riga. Also of some significance is the river Neva flowing into the Gulf of Finland and linking the Russian interior with the Baltic via lakes Ladoga and Pskov.8 The rivers flowing from the interior of the Scandinavian peninsula into the Gulf of Bothnia became of significance only with the opening up of northern Sweden in the nineteenth century. The whole coast of the Baltic is low-lying and provides few good natural harbours, although the southern coast offers comparatively frequent sheltering river mouths such as that of the Oder and inlets such as the Bay of Pucka (Putzig) north of Danzig.9 The Sea itself is comparatively shallow, especially at its outlets; the Sound and the Belts have saddle depths of only about 35 m. The paucity of deep channels and the plenitude of small islands in coastal waters have strongly influenced the character of naval warfare in the area and distinguished it from that of the open waters beyond; large deepdraught vessels have been unable to penetrate extensive strategic stretches of water.

The climate of the region is continental, modified by maritime influences. The Sea’s considerable length north to south (over ten degrees of latitude) means that there are appreciable differences in winter temperatures. Ice usually forms along the whole coast in winter and in normal years in the twentieth century the northern part of the Gulf of Bothnia, the narrow channels through the archipelago at its southern end and the Gulf of Finland are frozen over during the winter months. In particularly severe winters the narrower channels in the southern Baltic can also be ice-bound for brief periods, while drift ice can hinder navigation for longer.

During the socalled ‘Little Ice Age’, a period which began before and extended beyond our period, severe winters were more frequent and freezing could be more extensive. This could have serious effects on communications, particularly across the Gulf of Bothnia. The Sound and the Belts might on occasion freeze over to a considerable depth, and naval actions and seaborne trade were largely limited to the spring, summer and early autumn.10

In the north of the region the severity of the climate as well as the short growing season have discouraged settlement. In the south nature has been more generous. The plains bordering the southern and south-eastern coasts and the Danish islands provide potentially rich grain-growing areas. Further north mixed farming has been the rule; only in exceptional years was there a surplus of grain with which to trade. But other resources have provided some compensation. An almost continuous belt of forests stretching from southern Sweden to southern Finland and eastward into Russia has not only offered plentiful timber for building and other domestic purposes but also provided tar for preserving ships’ timber and charcoal for the smelting of iron. The latter was of particular significance for the area of Bergslagen north-west of Stockholm, rich not only in good quality iron but also other metals in demand like copper and even small quantities of silver. The harvest of the sea has, since the sixteenth century, when the herring migrated into the North Sea, been rather meagre, and fishing as an occupation has been of only local significance.

Traditionally water in pre-industrial Europe bound people together rather than kept them apart. Transport by sea was generally easier and swifter than travel by land over roads which were often impassable, and the Baltic from Viking times acted as the main channel along which flowed goods between western and north-eastern Europe.11 The earliest nation state and for long the most important power in the Baltic grew up around the Sea’s exits and entrances. By the end of the Viking period in the eleventh century, the kingdom of Denmark, centring on the island of Zealand, embraced not only the surrounding islands and the Jutish peninsula but also the southern part of what is now Sweden (the provinces of Scania (Skåne), Halland and Blekinge). This encouraged its kings to claim the right to control all shipping sailing into and out of the Baltic, a symbol of which was the toll exacted from all merchantmen passing the castle of Elsinore (Helsingør) from 1429. In the course of the early Middle Ages Danish power spread along the southern coast of the Baltic as far as the river Oder and for a time established itself on the southern coast of the Gulf of Finland, where the Estonian capital of Tallinn (literally Danish fort) commemorates these activities. Of its medieval conquests only the island of Gotland remained in the middle of the sixteenth century, but the kingdom’s historical associations with both the north coast of Germany and with the south-eastern Baltic were never forgotten and were to play some part in Danish foreign policy in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

To the north of Denmark, the effective power of the Swedish monarchy was confined to what is now south-central Sweden and south-western and southern Finland as far as the eastern end of the Gulf of Finland.12 The country’s only access to the west lay through a narrow strip of coastline around the mouth of the river Göta, squeezed between the Norwegian province of Bohuslan to the north and the Danish province of Halland to the south and far from the heartland of the monarchy around lake Mälar.13 To the north, the Norwegian provinces of Jämtland and Harjedalen reached out towards the Gulf of Bothnia and further north still Sweden’s frontier with Norway, whose crown had been united with that of Denmark since 1380, was ill defined, a fact which was liable to lead to disputes between the two monarchies. The frontier between eastern Finland and Muscovy had in theory been delimited by the treaty of Nöteborg (Orechovets) in 1323, but this was liable to more than one interpretation, and disputes over it also caused friction, especially as the inhabitants on either side of it often moved about as if it did not exist, and the Swedish government actually encouraged settlement beyond it.14

Muscovy touched the Baltic only where the river Neva flowed into the easternmost end of the Gulf of Bothnia. This limit had been reached as the result of the absorption of the republic of Novgorod between 1471 and 1478, and in 1492 Tsar Ivan III had built there the fortress of Ivangorod opposite the Estonian port of Narva, to which he hoped it would become a commercial rival. It never did.15

To the south of the Gulf lay the most complex of the Baltic’s political units—an area referred to loosely as Livonia and occupying roughly the territory of the modern republics of Estonia and Latvia (the most northerly part was after the middle of the sixteenth century usually treated separately as Estonia (Estland), while the term ‘Livonia’ was confined to the area to the south). It consisted of a loose confederation of trading cities, most of whom were members of the Hanseatic League, ecclesiastical territories dominated by the archbishopric of Riga, and the estates of the Knights of the Sword or Livonian Order under their Grand Master, isolated in the eastern Baltic since the secularization of the parent Order of Teutonic Knights in 1525 as a result of the Protestant Reformation. All had since 1526 owed a vague allegiance to the Holy Roman Emperor in Vienna, who, however, took only an occasional interest in Baltic affairs. The original inhabitants of these lands, many of them still only nominally Christian, had long played a minor role in Livonian affairs; both political and economic life were dominated by German-speakers.16

South of the river Dvina began the sprawling grand duchy of Lithuania, united with the ‘Republic’ of Poland under the same king reigning in Cracow but retaining its own laws and institutions. Both Lithuania and Poland had only small coastlines, but between them lay that of the duchy of Prussia. This was ruled over by the successors of the last Grand Master of the Teutonic Knights, who had received it from the king of Poland when the Order was secularized and who still ruled it as a Polish vassal from his seat of power in the city of Königsberg (Kaliningrad). The king of Poland also exercised a claim to sovereignty over Danzig, the busiest of the Baltic’s ports, through which flowed the bulk of Poland’s grain and timber exports. The city, however, jealously guarded its privileges granted in the fifteenth century as reward for backing Poland against the Teutonic Order and which included freedom from taxation and a wide degree of autonomy.17 Further west the boundary of the Holy Roman Empire reached the Baltic. The two duchies of Pomerania and Mecklenburg which lay between this border and Danish territory were poor and backward. Pomerania’s main significance was as a barrier between the Baltic and the rising margravate of Brandenburg, whose ruling house of Hohenzollern had strong family ties with both Livonia and Prussia.

On the coast of Mecklenburg also lay the Hanseatic cities of Wismar and Lübeck, the former enjoying an uneasy relationship with its overlord, the duke of Mecklenburg, the latter an Imperial city owing allegiance only to the Emperor in Vienna and recognized as the leader of the League in the Baltic. The circle was completed by the two duchies of Holstein and Schleswig. The former lay within and the latter outside the Empire. Together they formed a jigsaw of lands, some ruled by the king of Denmark as duke of Schleswig-Holstein, some by various members of the Danish royal house of Oldenborg, and some administered jointly by king and dukes. On the Baltic coast of Holstein, the port of Kiel offered potential as a naval base.

2

THE BALTIC WORLD IN THE MIDDLE OF THE SIXTEENTH CENTURY

In the middle of the sixteenth century the Baltic was thus surrounded by three independent kingdoms—Denmark-Norway, Sweden-Finland and Poland-Lithuania; a number of secular principalities owing allegiance to the Holy Roman Empire—the duchies of Holstein, Mecklenburg and Pomerania and the lands of the Livonian Order; ecclesiastical territories in Livonia headed by the archbishopric of Riga; and surrounding the Sea in an arc from east to south-west, self-governing towns and cities, most of them members of the Hanseatic League—Narva, Reval, Riga, Elbing (Elblg), Danzig, Stralsund, Lübeck and Wismar.

Of the kingdoms, only Sweden was an hereditary monarchy and had become one as recently as 1544. Since finally breaking away from the Danish-dominated Kalmar Union in the early 1520s, King Gustav, the first of the house of Vasa, had built up a powerful position by his own personality and energy. For by western European standards his system of government was still rather primitive, relying as it did on the king’s close personal supervision with only a rudimentary civil service to carry out decisions. Central government headed by the Chancery lay within an itinerant court, travelling from royal castle to royal castle throughout the year in medieval fashion. While Stockholm was the largest town and the most important commercial centre of the realm, it was not to be a centre of administration for nearly a century. Local control was exercised through royal bailiffs in charge of estates which had grown considerably as a result of the Reformation settlement and from which much of the king’s regular income was drawn, and through the royal castellans. The system was financed largely by assigning the revenues (largely in kind) of royal farms for the support of specific offices. The considerable mineral deposits in central Sweden, in particular iron and copper, had been exploited since the early Middle Ages, but, in spite of Gustav’s valiant efforts and his success in building up a store of silver, the economy in general was backward, overseas trade small scale and largely in foreign hands, ready money in short supply, the land thinly peopled and the crown’s resources consequently limited1.

Royal power was restricted in theory by the terms of the medieval Land Law of King Magnus Eriksson. This bound the king to rule with the advice of his Council of great nobles (med råds råde as the phrase went) and by his coronation oath, and in practice by dependence on a nobility which monopolized all the great offices of state and, conscious of its own power, was jealous of any attempts by the king to increase his. The Diet (Riksdag), consisting of the Estates of nobles, clergy, burghers and peasants was not yet firmly established as an organ of government, but, as with Henry VIII and the English parliament, the king’s use of it to drive through the new religious settlement since 1527 had helped to strengthen its power. Its claim to approve significant changes in the law and to grant new taxes was already becoming accepted. The monarch, however, could—and did—still call together representatives of only one or two of the Estates to deal with matters he deemed relevant to them alone, or summon provincial meetings to discuss local issues. The limitations on the king’s powers were thus both in theory and practice quite considerable. But in matters of foreign policy, he had the final say.2

Denmark and Poland were elective monarchies. In both the crown had in practice passed for some time from father to son, but in Denmark the right of rebellion against an unpopular monarch had been exercised by the nobility as recently as the 1520s, when Christian II had been forced to make way for his uncle Frederik I, and the Council was able to force on each new monarch a Charter (håndfæstning) which obliged him to consult it on all matters of peace and war, on relations with foreign powers, and on the raising of taxes and troops.

In Poland the king was also expected to consult his noble Council on all important matters and to call regular meetings of the national Diet or Sejm. This consisted of two houses: a Senate of bishops, the chief officers of state and provincial governors; and a House of Representatives made up of all other members of the nobility (szlachta) able to attend, together with representatives of the city of Cracow. To this body the monarchy had to submit proposals for new laws and taxes. The royal bureaucracy was pitifully small, and the king’s need to rely on the Sejm for much of his war expenditure made it difficult for him to act decisively in foreign affairs and to take advantage of opportunities which were offered. Many of the great nobles in fact felt free to conduct their own relations with foreign princes, and the nobility as a whole claimed the right to form armed ‘confederations’ to oppose a king who, they felt, had infringed upon their rights.3

In Denmark the Estates (Stænder) of nobles, clergy, burghers and...

Table of contents

- COVER PAGE

- TITLE PAGE

- COPYRIGHT PAGE

- MAPS

- PREFACE

- THE HOUSE OF VASA

- RULERS OF THE BALTIC LANDS 1560–1790

- THE BALTIC 1558–1790: A CHRONICLE

- INTRODUCTION

- 1: SETTING THE SCENE

- 2: THE BALTIC WORLD IN THE MIDDLE OF THE SIXTEENTH CENTURY

- 3: THE STRUGGLE FOR LIVONIA (1558–95)

- 4: THE TIME OF TROUBLES (1595–1617/21)

- 5: THE BALTIC DURING THE THIRTY YEARS WAR (1618/21–48)

- 6: THE FIRST GREAT NORTHERN WAR (1648–67)

- 7: THE LATER SEVENTEENTH CENTURY (1667–1700)

- 8: CHARLES XII, PETER THE GREAT AND THE END OF SWEDISH DOMINANCE (1700–21)

- 9: A NEW BALANCE (1721–51)

- 10: MID-CENTURY CRISES (1750–72)

- 11: THE AGE OF GUSTAVUS III (1772–90)

- EPILOGUE: THE BALTIC IN THE REVOLUTIONARY AND NAPOLEONIC WARS (1790–1815)

- POSTLUDE: THE BALTIC IN THE NINETEENTH AND TWENTIETH CENTURIES

- NOTES AND REFERENCES

- BIBLIOGRAPHY

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access War and Peace in the Baltic, 1560-1790 by Stewart P. Oakley in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.