Chapter one

Water resources and food production in Jordan

Hassan A.K.Saleh

When discussing the economy of Jordan, one cannot ignore water and food. Water resources are considered a national asset and essential to satisfy the demand for food.

Scarcity of water is the most serious of several constraints that limit development of food production. Therefore, Jordan depends largely on rainfall for its water and food resources.

This chapter will include an evaluation of the present state of water and food in Jordan, and the role of man in exploiting and managing these important resources. The government, in cooperation with the private sector, has taken numerous measures aimed at developing these resources. Despite this effort, it has not yet been possible to achieve a reasonable degree of food self-sufficiency.

In the last few years Jordan has witnessed substantial social and economic changes which have made a major contribution to the expansion of domestic demand for foodstuffs. This has led to an ever-increasing reliance on food imports, which increased from an annual average of JD 41 million for the period 1973–5, to JD 179.9 million for the period 1981–5.

This chapter is divided into three parts. The first part deals with the land and the people of Jordan and is a basis for the following two parts. The second part discusses the present state of ground and surface water resources, with reference to the water balance and water use in irrigation. The third part analyses food production and its sufficiency, with reference to the factors affecting food supplies. A regression model was used to analyse these factors, in addition to other simple statistical methods which were used to compute variation and correlation coefficients, as well as self-sufficiency ratios.

Land and people

The physical background

Topography

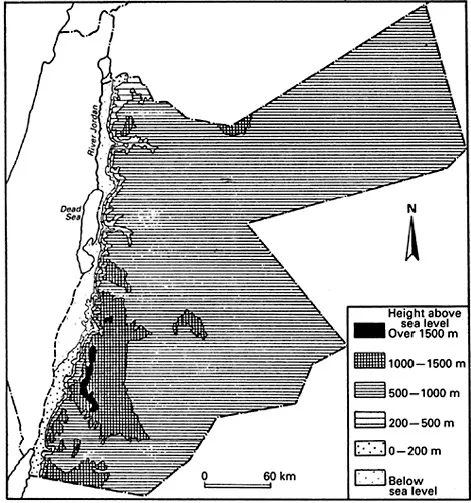

Jordan can be divided into three physiographic regions which are from west to east as follows: the Jordan valley, the highlands and the desert plateaux (Figure 1.1). The rift valley comprises the low lying Jordan Valley, the Dead Sea and the Wadi Araba. The Jordan River descends from below sea level at the Dead Sea. The valley through which the Jordan flows into the Dead Sea is about 105 km long and from 5 to 25 km wide. The river drains the water of Lake Tiberias, the Yarmouk and the few other streams and wadis from the side of plateau into the Dead Sea (Saleh 1971, p. 1; Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan 1973, p. 2).

The highlands east of the rift extend as a backbone of Jordan from the Yarmouk river in the north to Aqaba in the south. Several wadis and some twelve perennial streams cut across this upland area, dissecting it into many well-defined hills and plateaux. Four main blocks, however, are readily distinguishable, divided by the Yarmouk, Zarqa, Mujib, Balqa, Moab and Edom. Their height is about 1,200 m on average above sea level.

The desert plateau, lying east of the highlands, is by no means uniform. It rises about 600 m on average above sea level. Its undulating land is dissected by dry wadis descending from the highlands eastward, and draining inland into the depressions of Al Jafr, Al Azraq and Wadi Sirhan. Prominent landmarks in the desert result from past volcanic activity and from the exposure by erosion of durable volcanic intrusions known as inselbergs (Saleh 1975, pp. 19–20; Buheiry 1972, pp. 54–5).

Soil and vegetation

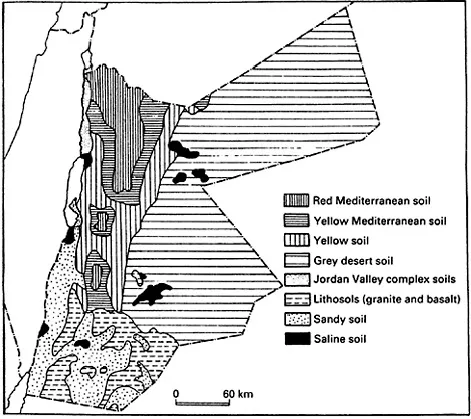

The different types of soil in Jordan are illustrated in Figure 1.2. In highland Jordan, limestone is usually weathered into calcareous or silt clay. This is an important soil-forming material, and in the wetter areas it assumes a typically reddish brown colour. It is usually heavy and only rarely contains the debris of the original limestone. Most of the food agricultural soils of the Jordanian plateau belong to these red Mediterranean soils (Aresvik 1976, pp. 22–3).

Yellow Mediterranean soils and regosols are also found in some parts of the highlands, in the scarps and in the Rift Valley. The sirrozems, on the other hand, are the grey desert soils covering about half of Jordan. Alluvial soils are found in the Jordan flood plain and in the bottoms of the valleys (Fisher et al. 1968, pp. 16–20). Most of the soils are rich in mineral components and poor in organic matter. Alluvial and red Mediterranean soils are the best of all soils in Jordan. When deep, these soils form excellent cropland. Their natural fertility is relatively high. On the whole, the problem of erosion and salinity is an obstacle to cultivation, and it often causes low productivity.

Figure 1.1 Relief features

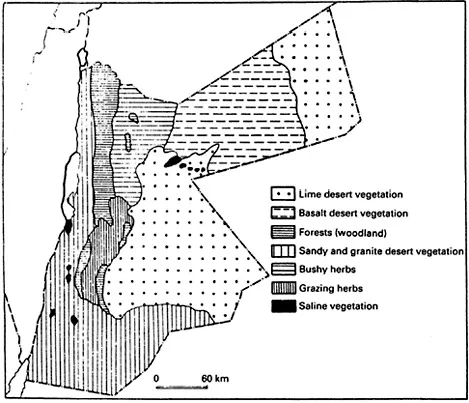

The flora of Jordan fall into three phytogeographical regions: the Mediterranean, the Irano-Turanian and the Saharo-Sindian. These three floral regions correspond to the three vegetational zones of forest, steppe and desert. The Mediterranean forest is scattered on the highlands, encircled by steppe grasses. The different types of vegetation are shown in Figure 1.3. The dominant species of the forest are pines and different varieties of oak and bushes, whereas that of the steppe is artemisia herba-alba and those of the desert are drought-resistant halophytic species (Eig 1951, pp. 112–14; Zohary 1962, p. 73).

Rainfall

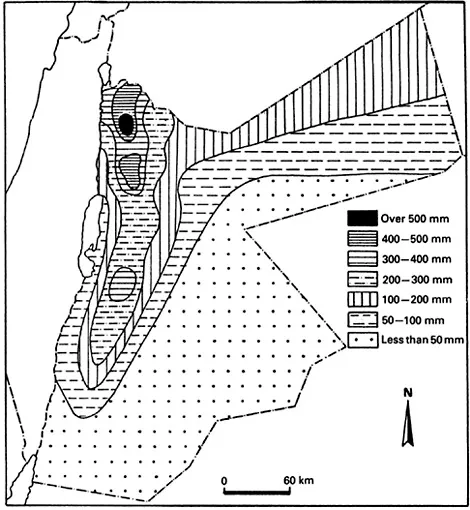

The total area of Jordan is 92,544 km2. Of this area, only 9 per cent receives more than 200 mm of rainfall and can be considered productive agricultural land. The area of marginal land (200–300 mm) is about 5.3 million dunums (1 dunum=0.1 hectare), or 5.7 per cent of the total area of Jordan. That of semi-arid land (300–500 mm) is about 1.7 dunums, or 1.8 per cent, and that of semi-humid land (500 mm and more) is about 1 million dunums, or 1.1 per cent of the total area (Duwayri 1985, p. 126).

It can be concluded that about two-thirds of the total area of Jordan receives less than 50 mm annually, this quantity representing more than one-fifth of the total rainwater. On the other extreme, 1 per cent of the total area receives more than 500 mm annually, this quantity representing about 8 per cent of the total rainwater falling in Jordan (see Table 1.1 and Figure 1.4).

The average rainfall quantity in Jordan is approximately 6,885 million m3, plus about 2,000 million m3 that fall on catchment areas outside Jordan. A large amount (about 75 per cent of the total rainfall) is lost through evaporation. It is estimated that about 15 per cent of the total rainfall flows down rivers and streams. About 10 per cent of the total rainfall percolates underground to replenish subterranean water, part of which will rise to the surface in the form of springs. Renewable water resources, surface and subterranean, are currently estimated at 1,200 million m3. Of this quantity, irrigated agriculture has used less than half (about 520 million m3) in 1985 (Ministry of Planning 1986, p. 497; Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan 1978, p. 7).

Table 1.1 Annual average rainfall for various areas of Jordan

Because of rainfall variation, annual changes in agricultural output have been very great. Wheat production in a good year may be four or five times that in a bad year (Mazur 1979, p. 147). The correlation between annual rainfall and both field crop areas and production is high. The north-western parts of Jordan receive the highest quantities of annual rainfall with the lowest coefficients of variation in rainfall and field crop production. In contrast, the south-eastern parts of Jordan receive lowest quantities of annual rainfall with highest coefficients of variation in rainfall and field crop production (Saleh 1975, p. 40) (Figure 1.5).

Not only is production of field crops affected by spatial variation of rainfall, but it is also affected by irregular distribution of rainfall during the course of the year. With the exception of the dry summers, rain falls during three periods of the year: in autumn (the early rain of October and November), in winter (the seasonal rain of December-February) and in spring (the later rain of March-May). In order to have a successful growing season, rain must fall during these three periods in sufficient quantities. If early rain is low in quantity or late, the field crops will be unable to grow. Moreover, late rain determines the extent of agricultural output, and extreme insufficiency may result in failure of both winter and summer crops.

Figure 1.4 Annual rainfall distribution, 1952–74

Successive dry years are disastrous for farmers. On average, rainfall is distributed as follows: October 2.6 per cent, November 7.7 per cent, December 20.7 per cent, January 23.5 per cent, February 19.7 per cent, March, 17.6 per cent, April 6.4 per cent and May 1.8 per cent (Saleh 1985, p. 31). The region of sufficient rainfall for cropping in a normal...