![]()

Part 1

New approaches to psychodrama theory

![]()

Chapter 1

Scheme of human development

(inspired by Moreno and Buber)

An approach to sanity and insanity*

This text combines the theories of Moreno and Buber with my experiences from clinical practice, which includes experiments carried out in a psychodramatic psychotherapy group, composed mostly of psychotics.

Bowlby's (1958) studies on “attachment”corroborate many of the affirmations made here. He offers a firm basis for the interpersonal theories I describe and for the foundation of “a relationship psychotherapy” – by which I mean psychotherapy which takes into account, as a technical procedure, the two-way (as opposed to unilateral) interaction established between patient and therapist.

Role reversal as a “measure”

From a practical perspective, a correlation between Buber and Moreno would have to begin with the encounter, the I–Thou (from hereon referred to as the I–you), their greatest point of convergence. Buber refers to role reversal (the psychodrama theory and technique) as “experiencing the other side”, an essential condition for the I–you encounter. Moreno's concept of role reversal represents the culmination of a development process (of the matrix of identity) in the human being. Hence, by means of the psychodramatic technique of role reversal (“experiencing the other side”) we would have the necessary tool for a practical study of Buber and Moreno. In other words, with the capacity “to reverse roles/experience the other”, we have the possibility for the encounter. Either allows us to see that a healthy person has the potential and capacity for the encounter since they would be capable of “reversing” or “experiencing the other”.

Through psychodrama and the technique of role reversal, the capacity to “reverse with or experience the other” can be measured. As such, one would be measuring the degree of health or sickness afflicting a person. Laing (1973) suggests that sanity or psychosis may be tested by the unity or disunity between two people. Role reversal proposes the same or goes even further. For Moreno (1977), personality begins to form with the development of roles. So, to study the personality formation, given the strict relationship between the “role process” and its formation, he presents “the role test” (1977, p. 161).

Acting out a role always suggests the presence of “another”. For each role there is a complementary role or counter-role. The relationship (mother–son, doctor–patient, etc.) emerges from the meeting of the two. Role and counter-role are “co-existent”, “co-acting”, “co-dependent” (Moreno, 1977). The presence of a great number of psychotic elements (during an outbreak or severe regression) in a personality would correspond to a total inability to play and reverse roles. Likewise, the total absence of psychotic elements (the ideal model) would result in a perfect role-reversal performance. Between these extremes lie the myriad variations. The “sign of not reversing roles”, means some healthy process has been altered. This is in agreement with Moreno's theory of the development of the matrix of identity (see diagram on p. 22), where, in regressive order, we would first have the “loss of role reversal”. Alteration of the intermediate phases would then take place, followed by the inability to perform one's own role (recognition of I ) leading to “indifferentiation”. An alteration in the ability to reverse roles would be the first indication of “sickness”.

It is important to note that a patient's capacity to reverse roles is not established in a single psychodramatic scene but throughout numerous scenes. First of all, the protagonist must be appropriately warmed up for the scene. Then, only by observing a series of psychodramatic sessions can one conclude to what point the patient is unable to reverse particular roles, a specific role, several roles, or all roles. Such observation permits one to confirm whether blocks in an emotional sector pertain only to a particular relationship, or if the block is more extensive or even global.

Neurotics1 are frequently incapable of performing in the role of the other. Roles, which contain strong emotional stress, lead to restricted spontaneity and performance. For example, in presenting a great inner conflict with a particular person in the psychodramatic scene, the person is unable to perform the role. The psychotic's block, especially during an outbreak or with “defects of personality”, is much more profound and intense, making role reversal a threatening experience.

Patients with processual evolution and consequent “defects” in chronicity are also unable to role reverse. However, when the personality is “conserved”, outside the psychotic episodes, it may be possible. I have observed that in the remission phases of cyclical psychosis patients manage reversal. Yet, in remission from schizophrenic outbreaks role reversal may be more difficult, depending on the intensity of the “defects”. With psychogenetic and/or reactive psychosis, the ability to reverse roles returns with the disappearance of the psychotic symptoms. Neurotics, or non-psychotics, including character neurosis or psychopathies, manage a considerably better performance of roles and role reversals, despite blocks sometimes existing for particular roles and for reversals. In short, the more sickness afflicting the personality, the greater the difficulty in playing and reversing roles – both in psychodrama and in life.

J. L. Moreno mentions (1975) that role reversal should be used carefully when a poorly structured individual is involved, especially when the other participant is a well-structured individual. For example, “double technique is the most important therapy for lonely people … A lonely child, like a schizophrenic patient, may never be able to do a role reversal but he will accept a double” (J. L. Moreno, 1975, p. 157). Precisely as one would expect, since the double stage corresponds to stages before the development of role reversal.

Referring to the Rojas-Bermudez (1975) role diagram, in neurotics the “self” would expand, hindering performance of the complementary role. In his own role, the individual would act according to stereotypes of all the neurotic conflicts accumulated during his life. The thought that this neurotically crystallized role or type of linkage could be transformed would generate panic. Thus, a block would exist for certain roles. In the psychotic, once something has set off this “alarm”, a highly expanded “self” would emerge as a supposed defense. In more severe cases expansion would disguise all vital roles, making connection with complementary roles difficult, if not impossible. Attempts to make contact are inhibited by this “self” barrier, perceived as threats of invasion and loss of boundaries (in patients in psychotic outbreaks and/or with “handicapped” personalities).

Mazieres (1970) states that in the psychotic patient the sequence would be: (a) alarm signal; (b) threat of being invaded and destroyed; (c) expansion of “self” as defense (covering up the roles) and; (d) difficulty or impossibility in performing roles (with role-to-role relationships there are no linkages). I add that, without linkages, the psychotic would find him/herself deprived of the you – alone in psychotic solitude.

J. L. Moreno (1975) states that human beings suffer fundamentally from the incapacity to realize all the roles that are part of them. They are always greater than their undertakings show, and this greatness is also the reason for their misery. Anguish arises from the pressure exerted by all these inadequately performed roles, roles that are repressed and demanding realization. In the psychotic, it is as if pressure and anguish are at a maximum. Under such pressure, the psychotic frequently explodes, performing megalomaniac and grandiose roles, as if to compensate for a long period of restriction. The resulting delirious roles are a rebellion against personality repressing procedures that hinder the free flow of forbidden roles.

Paths between reality and fantasy

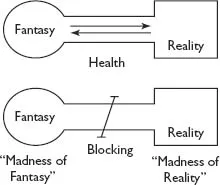

The psychotic, unable to distinguish fantasy from reality, regresses. According to Moreno (1977, p. 114) in “The Breach Between Fantasy and Reality Experience”, a child's development is accomplished through two preparatory processes – one related to real acts, the other to fantasy acts. The problem is not one of leaving the world of fantasy in favor of the world of reality, which is practically impossible. Rather, it lies in creating the means to enable the individual to master both situations, able to shift from one to the other. Nobody can live forever in a totally real world, nor in a totally imaginary one. The psychotic is blocked on the pathways that allow free transit between the two worlds and thus confuses them. He/she, therefore, has difficulty in getting out of him/herself – of being the other – of performing at the level of the “as if”, of the “make believe”, of fantasy. It might seem strange that, being in the realm of (pathological) fantasy, the psychotic is unable to interpret a scene's (psychodramatic) fantasy, dominated instead by a “fantastic rigidity”. The psychotic cannot reach the free path, the healthy exchange between the two worlds (as occurs to a greater or lesser degree in all psychotic patients).

Likewise, remaining exclusively in the realm of reality would be a “realistic rigidity”, a madness, “the madness of reality”. Henry Miller, in his magnificent essay on Rimbaud, says that the last desperate attempt to flee from madness is to become so completely wholesome that one does not realize one is mad: “Rimbaud never lost touch with reality, conversely, he held on to it like a maniac; what he did was abandon the true reality of his being” (1968, p. 112).

In these cases, the “tele” (Moreno) is altered. Psychotics are unable to grasp the surrounding world. Psychotics are unable to act, to get out of themselves and seek the other (Buber and Moreno). They submerge themselves in their transferential world.

A case study from group psychotherapy may illustrate the point: Joana, 28 years old, looked bored and annoyedly aloof. She was ostensibly indifferent to the environment, distrustful, introverted, inhibited, with schizoid retraction and a reduction of her “vital contact with reality” (Minkowsky, 1961). Her thought sequences seemed poor, clouded by continued fantasy. Some ideas were overvalued, compromising experiences. In the group, she would not state her opinion about the others when asked to, making personal complaints instead. She was unable to perform complementary roles during dramatizations, and found it extremely difficult to transfer herself to fantasy. Yet, whenever she did manage to, she had difficulty coming back to reality. On one occasion, during a group scene of a shipwreck, she removed the watch of one of the shipwrecked persons (played by an auxiliary ego). After the scene was over, and even after the end of the session, she refused to return the watch, arguing with elements from her “as if” role played in the dramatized scene. During another session, she performed with an auxiliary ego who played the role of a homosexual. Since then, she has always considered him to be homosexual.

Her inability to be the “other” during fantasy play and its mixture with reality, together with her inadequate emotional level, gives us an idea of the existential weakness and self-loss of existence.

The impossibility of being the other, the you, of performing and reversing roles according to Moreno, corresponds to the incapacity to experience or include the other side according to Buber. Under such conditions there is no capacity for mutuality and reciprocity. These patients find themselves mute to spell out the “basic words”. According to Moreno and Buber, this would be the failure of the encounter. Both conceive of man as the bearer of cosmic linkages and the cosmos as the great cradle of human beings. Since, for Moreno, man develops from the cosmos (through the matrix of identity) and, for Buber, man starts his evolution through the “basic words”, then Moreno's “indifferentiation” phases correspond to Buber's innate I–Thou. Through Moreno's “role reversal” and Buber's “experiencing the other”, man becomes fit for encounter, for a full “dialogical” relationship.

A scheme of human development

Performing the “role of the other” is not something that comes about suddenly and fully fashioned. It requires a whole sequence of develop mental stages that overlap and frequently operate jointly. For Moreno, the matrix of identity – comprised of five stages – is a child's first emotional learning process. The first stage is characterized by the child's inability to distinguish himself from his/her environment – he/she feels him/herself as one with the rest of the world (“oneness”). The second stage is characterized by the infant centering att...