![]()

Part I

GESTURES AND WORD LEARNING

![]()

Chapter 1

Gesture and the Emergence and Development of Language

Virginia Volterra

Maria Cristina Caselli

Olga Capirci

Elena Pizzuto

Institute of Cognitive Sciences and Technologies

Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche (CNR), Rome

Nature is a miser. She clothes her children in hand-me-downs, builds new machinery in makeshift fashion from sundry old parts…

(Bates, 1979, p. 1)

PREFACE (BY VIRGINIA VOLTERRA)

During the autumn of 2002, just a few weeks before we would discover about her disease, Liz and I were walking through Rome, talking about work and a dream we had. We wanted to write something together again, something about gesture—a topic in which we had been interested since we started our lifelong collaboration and profound friendship, about thirty years ago. We were aware that many of our old ideas about the role of gesture in children’s linguistic development were suddenly becoming extremely “modern” and we were planning to articulate our current perspective (old and new at the same time) by doing a critical review of recent work carried on in different laboratories and countries.

As we had done many times in the past, we started to write the manuscript “a due mani” (two-handed) but despite the attempts we made during the first half of this awful 2003, we did not have enough energy to complete that work.

The present chapter is meant to be a modest, partial attempt to realize that dream: it has been written “a quattro mani” (four-handed) by four peo ple of the “Nomentana Lab” who share a common debt: a debt of immense gratitude to Liz who has forever marked their life with her unique, intense depth and generosity, as a scientist and as a human being.

INTRODUCTION

We would like to frame our observations within the context of current discussions of the origins of language, a topic that has been debated, from different perspectives, since antiquity. Early accounts of language origins often contained speculations about the relationship between language and gesture, including the idea that our hominid ancestors communicated through hand signs, which served as the “missing link” in language evolution. Adam Kendon (2002) recently provided a very elegant review of theories about a gestural origin of language showing the relationship between these theories and a deep interest in deaf people and their signed communication, For example the eighteenth-century Neapolitan philosopher, Giambattista Vico, in La Scienza Nuova (1744/1953) formulated his theory on the origin of language according to which in the beginning, humans were mute and communicated by gesture, not by speech. Similar ideas on the first forms of language being rooted in action or gesture were debated at about the same time in Paris by such thinkers as Condillac and Diderot. For Condillac, language began in the reciprocation of overt actions, making its first form a language of action. This led Condillac to write about the language of gesture, both as this was practiced in the pantomimes of antiquity and as it might be observed among deaf people (Kendon, 2002:37).

In the nineteenth century comparative linguists like Bopp, Schleicher, Humboldt, and Muller, speculating on a universal language from which all modern languages were supposed to originate, formulated various hypotheses on the use of onomatopoeia and of so-called “acoustic gestures,” which may have originally accompanied expressive gestures but then became more sophisticated, and were progressively detached from gestures (Leroy, 1969).

The issue was even too much debated and in 1866 the Société de Linguistique banned papers on language origins, stating that: “The Society will accept no communication concerning either the origin of language or the creation of a universal language.” The London Philological Society did the same in 1872. The ban was so effective that the topic of language origins was almost ignored until the second half of the twentieth century when scientists from different disciplines like anthropology, paleontology, primatology, and linguistics came together for a symposium at the 1970 meeting of the American Anthropological Association. Many of the papers presented were collected and published a few years later in a volume entitled Language Origins (Wescott, Hewes & Stokoe, 1974). In order to get this book into print, Stokoe established a small publishing company, Linstok Press. This book put forward again the theory of a gestural origin of language showing that a great accumulation of ethological, neurological, and paleontological data relevant to the study of language made it possible to develop a scenario for the origins of language.

It is not accidental that around the same years a large body of research was developed in two areas strictly related to the above issue: sign language and language acquisition in deaf signing children. The study of the visual-gestural or signed languages used by deaf people has shown that gestures can, and indeed do develop into full-blown linguistic systems, with functions and properties that are largely comparable to those of vocal languages. This general result highlights the links and continuity that relate gestures to language systems. Due to the gestural substance of these languages, the comparative, crosslinguistic and crossmodal exploration of signed and spoken languages also provides unique insights with respect to the distinctive features of human language, the extent to which these can be influenced by the modality of production, and their evolutionary path (Annstrong, Stokoe & Wilcox, 1995).

The study of language acquisition by children exposed to sign language has highlighted interesting relationships between gestures and signs and between the acquisition of spoken and signed languages. Such comparisons have promoted remarkable advancements in the study of language development in human infants. Significant insights into the organization and evolution of language have been gained through studies aimed at clarifying the interplay between the vocal and the gestural modality in early development, and the more general cognitive roots and developmental precursors of language (Volterra & Erting, 1990),

The most recent formulation of a theory of a gestural origin of language has been provided by Corballis (2002) who, in his recent book From Hand to Mouth, has proposed that gesture has existed side by side with vocal communication for most of the last two million years, a hypothesis that has also been put forward by other scholars (Hewes, 1976; Armstrong, Stokoe & Wilcox, 1995; Deacon, 1997).

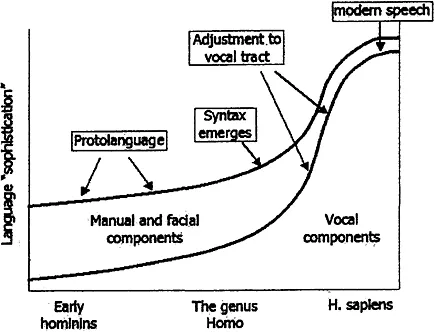

According to Corballis, something over 30 million years ago great apes differentiated from the Old World monkeys, and by around 16 million years ago larger brains probably heralded an increase in thinking, including enhanced representation of objects in the brain and the capacity of using a form of protolanguage. Around 5 or 6 million years ago, bipedalism was the main characteristic of early hominids that distinguished them from the other great apes and that had freed their hands and arms for more effective gesturing. But the advance from protolanguage to true grammatical language may not have begun until the genus Homo emerged, sometime around two million years ago. This branch of hominids was distinguished

by an increase in brain size, the invention of stone tools, and the beginnings of multiple migrations out of Africa, and it is likely that language became increasingly sophisticated from then on. For most of this period, language would have been primarily gestural, although increasingly punctuated by vocalizations. An indirect evidence of the gestural origin of language is that articulate speech would have required extensive changes to the vocal tract along with the cortical control of vocalization and breathing. The evidence suggests that these were not completed until relatively late in the evolution of the genus Homo (see Fig. 1.1, from Corballis, 2002:118).

The adaptations necessary for articulate vocalization may have been selected, not as a replacement for manual gestures, but rather to augment them. Since many species show a left-hemispheric dominance for vocalization (a bias that may go back to the very origins of the vocal cords), as vocalizations were increasingly incorporated into manual gesture, this may have created a left-hemispheric bias in gestural communication as well Homo sapiens discovered that language could be conveyed more or less autonomously by speech alone, and this invention may have been as recent as 50,000 years ago (Corballis, 2002). Gesture was not simply replaced by speech. Rather, gesture and speech have coevolved in complex interrelationships throughout their long and changing partnership. If this account is correct, then both modalities should still exhibit evidence of their prolonged co-evolution, reflected in certain universal (or near-universal) interdependencies, as well as predispositions that reflect the comparative recency or antiquity of these abilities (Deacon, 1997).

The tight relationship between language and gesture described above is compatible with recent discoveries regarding the shared neural substrates of language and meaningful actions that, in the work developed by Rizzolatti’s laboratory (Gallese, Fadiga, Fogassi & Rizzolatti, 1996; Rizzolatti & Arbib, 1998) have been likened to gestures, Specifically, Rizzolatti and his colleagues have demonstrated that hand and mouth representations overlap in a broad frontal-parietal network called the “mirror neuron system,” which is activated during both perception and production of meaningful manual action and mouth movements. The discovery of “mirror neurons” in the monkey brain provided a significant support to the notion of a gestural origin of language. These neurons respond both when the monkey makes a grasping movement and when it observes the same movement made by others. Since the mirror-neuron system is present in both monkeys and humans, it was most likely present in the common ancestor, providing a basis for a form of communication that was voluntary and flexible rather than fixed (Corballis, 2002).

In the present chapter we review a set of studies conducted in our laboratory that bear on the broader issues outlined above. These studies provide evidence on the continuity between prelinguistic and linguistic development, and on the interplay between the gestural and the vocal modalities in both typically developing children and in children with Down and Williams syndromes, whose development proceeds in atypical conditions. Corballis’ (2002) evolutionary views on a slow transition from gesture to vocal language appear to be supported by our developmental data, as this transition, and the interdependency between gesture and speech, seem still evident in children’s communicative and linguistic development. As observed by Deacon, it is of course unlikely that language development recapitulates “language evolution in most respects (because neither immature brains nor children’s partial mapping of adult modern languages are comparable to mature brains and adult languages of any ancestor)” (Deacon, 1997 p. 354), but we can gain useful insights into the organization and evolution of both language and gesture by investigating the interplay between these modalities in the communication and language systems of children with typical and atypical development.

EARLIER WORK ON GESTURE AND THE EMERGENCE OF LANGUAGE

The first investigation on the role of gesture in the emergence of language conducted at our institution was a longitudinal (for that time pioneering) study by Bates, Camaioni, and Volterra (1975). That study involved three infant girls aged 2, 6, and 12 months, at the beginning of the study, observed (with home visits at two-week intervals) over a period of eight months. At the end of this period the three infants overlapped one another in development. The study aimed to explore:

• the continuity from precommunicative schemes, to preverbal communication, to verbal interaction;

• cooccurring developments in other domains, such as nonver...