- 260 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Anne Bangfocuses on the ways in which a particular Islamic brotherhood, or 'tariqa', the tariqa Alawiyya, spread, maintained and propagated their particular brand of the Islamic faith. Originating in the South-Yemeni region of Hadramawt, the Alawi tariqa mainly spread along the coast of the Indian Ocean. The Alawis are here portrayed as one of many cultural mediators in the multi-ethnic, multi-religious Indian Ocean world in the era of European colonialism.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Sufis and Scholars of the Sea by Anne Bang in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Middle Eastern History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

THE ĀL BĀ(BANĪ) ‘ALAWĪ

Aḥmad b. Sumayṭ, like several of his fellow East African ‘ulamā’, was a scion of mad b. Sumayṭ a clan originally from Ḥaḍramawt, a region in the south-east of what is today the Yemen Arab Republic. Claiming descent from the Prophet Muḥammad, this group has considerable prestige both in their original and adopted homelands. In order to trace the impact of scholars like Ibn Sumayṭ on the history of Muslim East Africa, it is necessary first to understand the tradition in which they were formed. This tradition first came to evolve in Ḥaḍramawt.

The Ḥaṭ ramawt and the Āl Bā ‘Alawīad

There exists a considerable literature on Ḥaḍramī history and social organisation.1 Although more recent research2 has questioned the rigidity of the social system described by earlier authors, the distinct Hadramī stratification system remains a natural starting point for a survey of the ‘Alawī homeland. It must be noted that the above-mentioned literature all stems from the twentieth century, i.e. the 1950s and onwards. This means that caution must be exercised when trying to project backwards in time surveys undertaken a hundred years later. What can be said is that we have no indication that Ḥaḍramī society was organised along entirely different lines in the nineteenth century; the stratas described in twentieth-century literature are well represented also in the historical material.

The Ḥaḍramī stratification system was inextricably linked to the concept of nasab (genealogical descent). The more worthy his nasab, the higher the individual would find himself in the social hierarchy. In the top stratum were the sāda (sing. sayyid), who claimed descent from the Prophet Muḥammad. All Ḥaḍramī sāda genealogies trace their line to the Prophet Muḥammad via Aḥmad b. ‘Isā of Baṣra, Iraq, who migrated to the Ḥaḍramawt around 950 ADAD. The family name – Āl Bā ‘Alawī – refers to a grandson of Aḥmad b. ‘īsā named ‘Alawī (b. ‘Ubayd Allāh b. Aḥmad). Over time his descendants became a large, influential and tightly-knit religious stratum with several segmentary sub-branches known by a family name usually derived from the founder.

Apart from the sāda, two other strata held considerable influence and power in Ḥaḍramawt. These were the mashā’ikh (sing.: shaykh) and qabā’il, (sing. qabīla) i.e. the religious scholars of non-sāda origin and the tribesmen. Both groups trace their ancestry to Qaḥḥṭān, the eponymous ancestor of the southern Arabs. Whereas a mashā’ikh nasab would typically include a number of holy men and scholars of the past, a tribesman’s nasab would recount a lineage of heroic tribal warriors. The mashā’ikh stratum thus possessed an ascribed religious status, whereas the tribesman’s status was tied to his ability to defend his sharāf (honour), hence the tribal prerogative of carrying arms.3 The mashā’ikh would typically reside in towns, and engage in scholarly activities – often side by side with the sāda, inferior to them only because of the latter’s superior nasab. The qabā’il typically inhabited specifically demarcated territories in the countryside, quarrels over which often caused long-standing feuds.

Finally, at the bottom of the hierarchy, we find the people who had no nasab, thus possessing neither baraka, religious status nor sharāf. These were slaves or descendants of slaves, or immigrants of no known genealogical origin, known collectively as masākīn (poor) or ḍu‘afā’ (weak). Also in this group was placed resident traders, fishermen and craftsmen of unknown origin.

The Ṭarīqa ‘Alawiyya

Since early in their history, the main social glue of the Ḥaḍramī ‘Alawīs has been the ṭ arīṭarṭ arīīqaṭarṭ arīṭarṭ arīīqaīqa ‘Alawiyya, a Sufi order perpetuated by the Ḥaḍramī sāda until the present.

As R. B. Serjeant has pointed out,4 little is known about the religious beliefs held by the early Ḥaḍramī sayyids, who only later emerge as clearly Shāfi‘ī-Sunnis. Slightly clearer, but nevertheless covered in centuries of hagiography and perpetuation of legends, is the origin of the ṭ arīṭarṭ arīīqaṭarṭ arīṭarṭ arīīqaīqa ‘Alawiyya. Organised mysticism took root in Ḥaḍramawt during the time of Muḥammad b. ‘Alī, known as al-Faqīh al-Muqaddam (d. 1255). He was the great-great grandson of ‘Alawī, the eponymous founder of the clan, and was by all accounts particularly important for the introduction of organised Sufism to Ḥaḍramawt.

Spiritual organisation: The spiritual and genealogical bond

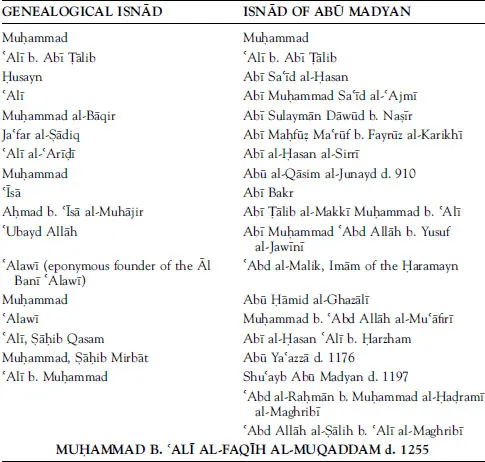

According to ‘Alawī expositions, the ṭ arīṭarṭ arīīqaṭarṭ arīṭarṭ arīīqaīqa ‘Alawiyya rests on a dual isnād: one which was passed on in the family line and one which was introduced from the Maghrib through the process of Sufi initiation. The former is believed to have been brought to Ḥaḍramawt by Aḥmad b. ‘īsā al-Muhājir, while the second arrived during the time of al-Faqīh al-Muqaddam. Both are interpreted as ṭ arīṭarṭ arīīqaṭarṭ arīṭarṭ arīīqaīqas in the Sufi sense – even the ṭ arīṭarṭ arīīqaṭarṭ arīṭarṭ arīīqaīqa that follows genealogy. One is, in other words, not simply born into the ‘Alawī ṭ arīṭarṭ arīīqaṭarṭ arīṭarṭ arīīqaīqa – one is initiated by a system of khirqa – the cloth or robe symbolising initiation. This comes out very clearly in the exposition by Ibn Sumayṭ in Tuḥfat al-Labīb5 where he describes the first ṭ ariqa which al-Faqīh al-Muqaddam took from his father. This chain of transmission is traced back to the prophet Muḥammad, and beyond him via the angel Gabriel to the ultimate fount to mystical knowledge, God himself. This chain of transmission embodies the baraka connected with Sharīfian descent.

Ibn Sumayṭ,6 ‘Abd al-Raḥmān al-Mashhū r7 and J. S. Trimingham8 agree that the second isnād of ‘Alawī Sufism originally derives from the Maghrib – more specifically from the teachings of Andalusian-Maghribi teacher Shū‘ayb Abū Madyan (d. 1197). According to the account given by Ibn Sumayṭ, Abū Madyan sent one of his foremost students, a man named ‘Abd al-Raḥmān b. Muḥammad al-Ḥaḍramī al-Maghribī eastwards towards Ḥaḍramawt. Before reaching Ḥaḍramawt he stayed in Mecca where he associated with another Maghribī Sufi: ‘Abd Allāh al-Ṣramawt, but before his death he instructed ‘Abd Allāh āliḥ al-Maghribī. ‘Abd al-Raḥmān died in Mecca without reaching theḥaḍal-Ṣāliḥto go to Tarīm where he predicted that he would find Muḥammad

Figure 1.1 Dual isnād of the ṭ arīṭarṭ arīīqaṭarṭ arīṭarṭ arīīqaīqa ‘Alawiyya

Source: Aḥmad b. Sumayṭ, Tuḥfat al-Labīb, on the basis of Muḥammad al-Shillī, al-Mushra‘ al-Rawī. b. ‘Alī, known as al-Faqīh al-Muqaddam. In this manner the isnād of Abū Madyan was passed on to Ḥaḍramawt.9 This isnād, too, is understood to be traced back to the Prophet.

It is worth noting that the isnād of Abū Madyan one generation later became the spiritual origin of the Shādhiliyya as propagated by Abū al-ḥ asan al-Shādhilī (d. c. 1258). The ṭ arīṭarṭ arīīqaṭarṭ arīṭarṭ arīīqaīqa ‘Alawiyya, as the Sufism of the Ḥaḍramī tsāda came to be known, can thus in many respects be considered an offshoot of the same origin, on par with the Shādhiliyya. This common spiritual origin serves to explain the strong doctrinal connection between the ethics and literature of the Shādhiliyya and the ‘Alawiyya. One example may be cited from the Comoro Islands, where the Shādhiliyya-Yashrūiyya was introduced during the nineteenth century. Those ‘Alawīs already present on the islands saw little or no contradiction in joining the Shādhiliyya, as the ‘Alawiyya was said to be ‘‘Alawī on the outside and Shādhilī on the inside’.10

In the centuries that followed al-Faqīh al-Muqaddam, the ‘Alawīs, like the Shādhiliyya, continued to emphasise such classical works as Abū Ḥāmid Muḥammad al-Ghazālī and al-Suhrawardī.11 The works of Ibn al-‘Arabī seem to have been known, but controversial. Ibn Sumayṭ sums up the Sufi aspect of classical Ḥramī learning when he in 1924 advised his son to study the works aḍof al-Ghazālī, particularly the Iḥyā’‘Ulūm al-Dīn, which was completed around 1100. According to Ibn Sumayṭ, this was the ‘book to which the forefathers devoted themselves’.12 Moreover, the ‘Alawiyya, like the Shādhiliyya, coupled mysticism with a strong emphasis on the Sharī‘a, both as the science of jurisprudence (fiqh) and as a way of life. Over time, fiqh came to be considered the basis of all knowledge, including mystical insight. For the ‘Alawī sāda, this meant Shāfi‘ī fiqh, and particularly the Minhāj al-ṭālibīn by Muḥyī al-Dīn Abū Zakariyyā al-Nawawī (d. 1277). Again, Ibn Sumayṭ sums it up for his son when he writes that ‘... you should have the books of Imam al-Nawawī and others of those who worked on the Sharī‘a, such as al-Sha‘rānī, and Ibn ‘Aṭā’ Allāh and that which gives the way of the Shādhiliyya and others’.13 It is worth noting here that Ibn Sumayṭ specifically advises his son to read the works of Ibn ‘Aṭ ā Allāh al-Iskandarī (d. 1309) and ‘Abd al-Wahhāb b. Aḥmad al-Sha‘rānī (d. 1565). Both these Egyptian ‘ālims were trained in the way of the Shādhiliyya and came to have considerable impact on the spread of its teachings. The former – Ibn ‘Aṭ ā Allāh, with his works Laṭ ā’if al-Minan and al-ḥ ikam – was especially important as a transmitter and legitimiser of Shādhilī tenets to the Middle East, while al-Sha‘rānī primarily elucidated ethics and the relationship between mysticism and the Sharī‘a.

Despite common ground in terms of teachings and ethics, the ‘Alawiyya cannot be considered simply another offshoot of the Abū Madyan-Shādhiliyya. The difference lies primarily in the ‘Alawī claim to special baraka based on Sharīfian descent from the Prophet, an aspect which at times – at least viewed from the outside – seems to overshadow the mystical content. Instead, it is more correct to define the ‘Alawī ṭ arīṭarṭ arīīqaṭarṭ arīṭarṭ arīīqaīqa as a transmission of mystical knowledge in the genealogical chain, which then was infused with the Madyaniyya during the lifetime of al-Faqīh al-Muqaddam. From that point on, it developed into a Sufi order – a ṭ arīṭarṭ arīīqaṭarṭ arīṭarṭ arīīqaīqa – which combined the methods, rituals and basic theological tenets of the Madyaniyya with an undefined set of mystical qualities perceived to rest in the bloodline of the Prophet.

Spiritual organisation and social stratification

Apart from what is said in the Sufi-biographical works of the ‘Alawiyya, we have no knowledge of when exactly the ṭ arīṭarṭ arīīqaṭarṭ arīṭarṭ arīīqaīqa ‘Alawiyya became a family affair, perpetuated in Ḥaḍramawt by the sāda. Most likely, the internal, clan-oriented characteristics were propagated from the very beginning, by al-Faqīh al-Muqaddam. As described above, he perpetuated the spiritual isnād of the Madyaniyya as well as a more primary isnād which went from father to son. One important hint in this direction is given in the Shams al-Z ahīra, which states that al-Faqīh al-Muqaddam himself used to carry arms (sword), ‘like others of the ‘Alawiyyīn’.14 However, after his introduction to Sufism, al-Faqīh al-Muqaddam ‘broke his sword’. As Sufi ideas spread, so other ‘Alawīs followed his example.

Admittedly on scanty evidence, it is tempting to link the spread of organised Sufism in the thirteenth and fourteenth century to the emergence of the ‘Alawīs as a distinct, unarmed, exclusively religious stratum of Ḥaḍramī society, distincṭ also from the indigenous religiouṢ group, the mashā’ikh. As Serjeant has pointed out, the ‘Alawīs did not really have a special status during their first centuries in the wādī: ‘In the first stage of their history the Ḥaḍramī perhaps regarded the ‘Alawī Saiyids as only one of these Mashāyikh groups – [. . .], and far from creating an immediate impression on the country, it was some time before they established their far-reaching claims to a privileged position [. . .]’15 Organised Sufism may be one factor which set the sāda apart, coupled with a general abandonment of weapons. Far from suggesting that the sāda put away their swords (which in fact is only partially true) because they turned to mysticism, it may be suggested that the two in combination caused the ‘Alawīs to emerge not as a shaykhly clan among many, but as a distinct stratum. The process of consolidation by no means happened overnight. According to the study by E. Peskes,16 early ‘Alawī Sufism was more of a vague set of clan rituals than a coherent order. The actual tenets, as they came to be formulated, can be linked to emergence of ‘Alawī Sufi literature in the fifteenth and sixteenth century i.e. some two-to three hundred years after al-Faqīh al-Muqaddam.

The fifteenth and sixteenth century can also be linked to another phenomena which has been predominant in sāda history: the transformation of spiritual power into worldly influence. By the 1400s and 1500s, we find a number of sāda who take the title ṣāhib (‘master of’) a particular town or place.17 They now emerged as a stratum of ‘holy men’, arbitrators, establishers and protectors of ḥawṭas (sacred enclaves – usu...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Indian Ocean Series

- Figures

- Plates

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1: The Āl Bā(Banī) ‘Alawī

- 2: The Āl Bin Sumayṭ

- 3: Aḥ Mad B. Abī Bakr B. Sumayṭ Childhood and youth in the Comoro Islands

- 4: ḥaḍramawt Revisited Family and scholarly networks reinforced

- 5: Travelling Years Zanzibar–Istanbul–Cairo–Mecca–Java–Zanzibar, 1885–1888

- 6: Ibn Sumayṭ, The ‘Alawiyya and the ShāFi‘ī ‘Ulamā’ of Zanzibar C. 1870–1925 Profile of the learned class: Recruitment, training and careers

- 7: Scriptural Islam in East Africa: The ‘Alawiyya, Arabisation and the indigenisation of Islam, 1880–1925

- 8: The Work of a Qādī Ibn Sumayṭ and the official roles of the Zanzibari ‘ulamā’ in the British-Bū Sa‘īdī state, c. 1890–1925

- 9: Educational Efforts Within the Colonial State Ibn Sumayṭ , the ‘ulamā’ and the colonial quest for secular education

- 10: The Death of a Generation

- Conclusion

- Appendix: The Writings of Aḥ Mad B. Abī Bakr B. Sumayṭ

- Notes

- Sources

- Bibliography