![]()

1 Studying Hong Kong from a comparative perspective

An anomaly for modernization theory (1980–mid-2002)

Problem-setting: the Chinese Government’s opposition is not a sufficient reason for the absence of democracy in Hong Kong

Three years before the twentieth century drew to an end, Britain withdrew from Hong Kong, the most glowing colony it has ever governed throughout its colonial history. Hong Kong, a place where East meets West, where robust Chinese entrepreneurship prospers under a British legal system, is an invaluable “asset” and an economic powerhouse.1 However, Hong Kong’s political development has been dwarfed in comparison with those splendid economic achievements. The handover of the most prosperous British colony in 1997 to China, the most powerful post-totalitarian regime that still remains (Linz and Stepan, 1996), has sparked international concern since the 1980s. The international community is worried whether Hong Kong can maintain its prosperity, freedom, and stability after reverting its sovereignty.

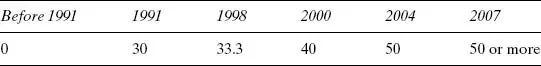

There are two research problems to be explored in this book. First, why has Hong Kong constituted a rare anomaly to the popular modernization theory, i.e., achieved a high degree of socio-economic development without attaining a high degree of democracy? Second, what have been the constraints on Hong Kong’s democratization, especially between 1980 and mid-2002, i.e., when Hong Kong’s sovereignty reverted to China for five years? Given that the pre-handover Hong Kong and British Governments have attempted to democratize Hong Kong since 1984, and that for a long time Hong Kong has had a very favorable level of socio-economic development suitable for developing democracy, why was democracy, as defined by Dahl,2 so lacking in Hong Kong between the mid-1980s and mid-2002, and why has full democracy been and will be precluded with at least until 2007 (Table 1.1)?3

In face of the well-publicized Chinese Government’s opposition to Hong Kong’s democratization since the mid-1980s, one is tempted to argue that the opposition from the Chinese Government was a sufficient cause to explain the absence of a high degree of democracy in Hong Kong.

Table 1.1 Actual and planned proportion of seats in the legislature directly elected between 1991 and 2007 (%)

On closer scrutiny, it can be observed that such a claim, however, is built on shaky ground.

Between 1982 and 1984, Hong Kong’s planned return to China posed a problem to the colony. To preserve Hong Kong’s economic value for China, and to persuade Taiwan to eventually reunify, the Chinese Government promised the Hong Kong people “One Country, Two Systems,” and a high degree of autonomy after 1997. But, as Hong Kong increasingly demanded Western-style democracy, the Chinese Government was forced to face up to its contradictory interests by either imposing more blatant obstructions or granting more concessions. It was also these contradictions in its interests that allowed Britain and local pro-democracy forces some limited room to maneuver.

In 1990, when the Chinese Government promulgated the Basic Law – the mini-constitution stipulated by the Chinese Government for post-1997 Hong Kong – in face of the ardent and vocal demands for faster and greater democratization from Britain and domestic pro-democracy forces, it allowed the direct elections of legislators in 1991 to increase phenomenally from ten to eighteen seats. In addition, a directly elected Chief Executive and a fully directly elected legislature will become possible in 2007, rather than 2011. The Chinese Government also stated that a steady progression of democratization between 1997 and 2007 would be allowed, despite its earlier warning in late 1989 that the democratization after 1997 would subsequently halt for ten years. Those concessions entailed contradictions in the Chinese Government’s interests with respect to Hong Kong, which made room for bargaining between China, Britain, and domestic pro-democracy forces. However, the moderate instead of major concessions to the local pro-democracy movement implied the limited bargaining power of the pro-democracy forces. This study will thus explore what other constraints, in addition to the Chinese Government’s opposition, have restricted the bargaining power of the pro-democracy forces. Hence, although the Chinese Government’s opposition during the 1980s and 1990s is important in explaining the actual and the scheduled slow pace of democratization between 1986 and 2007 (Table 1.1), other constraints need to be admitted.

Theoretically speaking, examination of the case of Hong Kong also makes good sense. The absence of full democracy and the expected and actual slow pace of democratization in Hong Kong between 1986 and 2007 render Hong Kong a rare and inexplicable anomaly to modernization theory. According to modernization theory, countries with a medium to high level of socio-economic development are likely to see the emergence and consolidation of a democratic system. However, from 1987 onwards, while Hong Kong has already been a “high-income economy” (World Bank, 1988–2001), it still remains an undemocratic city–state. Thus, Hong Kong has posed an anomaly to modernization theory and this research aims to draw theoretical implications for the theory from the case study of Hong Kong. The next few sections will argue that, despite some misgivings, modernization theory has been significant in explaining global democratization, and that Hong Kong has been a rare anomaly.

Global democratization and modernization theory

Since 1974, a global wave of democratization has swept over different parts of the world. Between 1974 and 2001, the number of new electoral democracies rapidly increased from 39 in 1974 to 121 in 2001 (Freedom House, 2002). In 2001, the 121 electoral democracies already represented more than 62.5 percent of the world’s population (Lipset et al., 2000). Although the numbers of electoral democracies have flattened out since the mid-1990s, and the prospect of democratic consolidation in different countries remains unclear, the third wave of global democratization has fundamentally altered the political contours of the world with the increase of over eighty-one new electoral democracies since 1974 (Diamond, 2000: 15; Lipset et al., 2000).

Causes of democratization and modernization theory

While many causes, including crises, education, urbanization, cultural values, religious beliefs, institutional arrangements, economic dependency, and economic development have all been cited as important for democratization (Huntington, 1991: 37–8; Shin, 1994: 135–70; Linz and Stepan, 1996; Bratton and Van de Walle, 1997: 19–60), the dominant approach has been modernization theory. This theory has two forms: in its weaker version, it asserts the existence of a general positive association, though not strictly linear, between the level of socio-economic development and the existence of “democracy” (Dahl, 1971: 20–1, 65; 1989; Rueschemeyer et al., 1992: 29). In its stronger version, it maintains that the level of socio-economic development is an important and, at times, the most important causal factor in determining the existence or level of democracy. The theory has received overwhelming support from cross-national research, adopting diverse research sam...