eBook - ePub

Motor Cortex in Voluntary Movements

A Distributed System for Distributed Functions

- 448 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Motor Cortex in Voluntary Movements

A Distributed System for Distributed Functions

About this book

As one of the first cortical areas to be explored experimentally, the motor cortex continues to be the focus of intense research. Motor Cortex in Voluntary Movements: A Distributed System for Distributed Functions presents developments in motor cortex research, making it possible to understand and interpret neural activity and use it to recons

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Section II

Neuronal Representations in

the Motor Cortex

3

Motor Cortex Control of a Complex

Peripheral Apparatus: The Neuromuscular

Evolution of Individuated Finger Movements

Marc H.Schieber, Karen T.Reilly, and Catherine E.Lang

ABSTRACT

Rather than acting as a somatotopic array of upper motor neurons, each controlling a single muscle that moves a single finger, neurons in the primary motor cortex (M1) act as a spatially distributed network of very diverse elements, many of which have outputs that diverge to facilitate multiple muscles acting on different fingers. Moreover, some finger muscles, because of tendon interconnections and incompletely subdivided muscle bellies, exert tension simultaneously on multiple digits. Consequently, each digit does not move independently of the others, and additional muscle contractions must be used to stabilize against unintended motion. This biological control of a complex peripheral apparatus initially may appear unnecessarily complicated compared to the independent control of digits in a robotic hand, but can be understood as the result of concurrent evolution of the peripheral neuromuscular apparatus and its descending control from the motor cortex.

3.1 INTRODUCTION

Unlike a robotic hand that has been designed by human engineers, the primate hand has evolved from the pectoral fin of a primordial ancestor. What began as interconnected bony rays supporting a fin evolved into a hand with digits capable of relatively independent motion. During this evolution, the pressures of natural selection concurrently influenced both the peripheral musculoskeletal apparatus and the central mechanisms for its neural control. The resulting biological hand, which has reached its most sophisticated form in primates, especially humans, nevertheless retains many structural and functional features of the ancestral appendage. To understand how the motor cortex participates in controlling finger movements, we must appreciate certain aspects of how the peripheral apparatus of a biological hand works. Here, we will consider first the motion of the fingers themselves, then the functional organization of the muscles that move the fingers, and then how M1 controls finger movements. Because M1 plays a particularly crucial role in controlling fine, individuated finger movements, we will focus on features that affect the independence of finger movements.

3.2 THE LIMITED INDEPENDENCE OF FINGER MOVEMENTS

Modern amphibians and reptiles have forelimbs with distinct digits, but do not use these digits to grasp objects. Further along the phylogenetic scale, mammals such as rats and cats can be observed to mold the digits of the forepaw to grasp objects.1–3 Although nonhuman primates, and especially humans, are clearly capable of more sophisticated finger movements, the vast majority of what nonhuman primates and humans do with their fingers consists simply of grasping objects. In grasping, all the digits are in motion simultaneously. Independently controlling the 15 different joints of the 5 digits presents a formidable problem for the nervous system, but analysis suggests that most control of the fingers in grasping could be simplified. Only 2 principle components—mathematical functions describing simultaneous motion of the 15 joints in fixed proportion to one another—account for most of the motion of the 15 joints.4,5 The first principle component corresponds roughly to the simultaneous motion of all the joints in the opening and closing of all the digits. The second principle component corresponds roughly to the degree of flexion of the fingertips toward the palm or extension of the fingertips away from the palm. Together, these two principle components account for 84% of the variation in finger joint positions used by humans in grasping a wide variety of common objects. Most of the finger movements used in grasping thus could be controlled by scaling just 2 principle components, a process much simpler than independently controlling 15 joints. Whether the nervous system actually employs such a simplifying scheme to control grasping, and if so, where in the nervous system the scheme is implemented, remains unknown as yet.

Beyond grasping, the fine finger movements used in manipulating small objects, typing, or playing musical instruments are performed much less frequently. Although the fingers commonly are assumed to be moving independently during such tasks, recordings show again that these sophisticated performances entail simultaneous motion of multiple digits.6,7 Even when specifically asked to move just one finger, both nonhuman primates and human subjects show some degree of simultaneous motion in other, noninstructed digits, whether moving the fingers isotonically, or applying forces isometrically.8–11

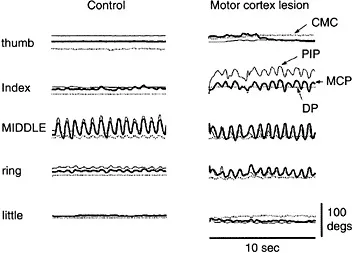

The crucial role of M1 in controlling fine, individuated movements of the fingers is evident from the common observation that such movements are the first affected and the last to recover when lesions affect M1 or its output via the corticospinal tract.12,13 Lesions of the motor cortex, besides rendering movements weak and slow, reduce the ability to move a given body part without concurrent motion of adjacent body parts, as illustrated for the fingers in Figure 3.1.14 From this perspective, the fingers can be hypothesized to have a fundamental level of control that produces general opening and closing of the hand for grasping.15 This fundamental control might be accomplished by rudimentary neuromuscular structures in the periphery and driven reliably by subcortical centers in the nervous system. As evolution progressed, a capability for more sophisticated control of the fingers may have developed on top of this fundamental level. This more sophisticated control required both subdivision of the peripheral neuromuscular apparatus and evolution of a computationally more complex layer of control, in which M1 plays a major role.

3.2.1 BIOMECHANICAL FACTORS

The fingers of a robotic hand are mechanically independent, but the fingers of a biological hand are coupled to a measurable degree by a number of biomechanical factors. Some degree of mechanical coupling between adjacent digits is produced by the soft tissues in the web spaces between the fingers. Cutting this tissue in cadaver hands reduced the extent to which adjacent digits moved along with a passively moved digit.16 Additional coupling is produced by interconnections between the tendons of certain muscles. In humans, the juncturae tendinium between the different finger tendons of extensor digitorum communis (EDC) are well known.17 The tendons of flexor digitorum profundus (FDP) to the four different fingers also are interconnected in the palm, both by thin sheets of inelastic connective tissue and by the origins of the lumbrical muscles.18 In macaque monkeys, these interconnections between the tendons of multitendoned muscles are more pronounced than in humans.19 In the macaque FDP, tendon interconnections have been shown to cause tension exerted at one point on the proximal aponeurosis of the insertion tendon to be distributed to the distal insertions on multiple digits.20

FIGURE 3.1 Loss of individuation after a motor cortex lesion. In these joint position traces, a control subject (left column) and a subject with a motor cortex lesion (right column) were instructed to move the middle finger back and forth while keeping the other fingers still. Joint position traces from the thumb are on top, followed by the index, middle, ring, and little (bottom) fingers. The thick lines show metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joint movement, the thin lines show proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joint movement, and the dotted lines show distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint movement, except for the thumb, where the dotted line shows carpometacarpal (CMC) joint movement. Joint position traces for the middle finger show that both subjects moved the middle finger as instructed. The control subject on the left made highly individuated movements of the middle finger with minimal changes in joint position of the noninstructed fingers. In contrast, the subject with a motor cortical lesion (in the contralateral precentral gyrus hand knob, extending into the white matter beneath) produced substantial changes in joint position of the index and ring fingers simultaneously with the middle finger movement.

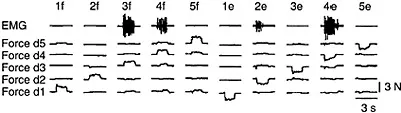

Because of this biomechanical coupling of the digits, muscle activity intended to move one digit will tend to move adjacent digits as well. To move one digit more individually then, additional muscles may be activated to check the coupled motion of the adjacent digits. Such stabilizing contractions have been observed in the electromyographic (EMG) activity of finger muscles in both monkeys and humans. As a monkey flexes its little finger, for example, extensor digiti secundi et tertii (ED23) contracts to minimize simultaneous flexion of the index and middle fingers.21 In humans, the portion of FDP that acts chiefly on the middle finger contracts as the subject extends either the index or the ring finger, apparently to minimize coupled extension of the middle finger (Figure 3.2).22

Additional requirements for stabilizing contractions result from the fact that the extrinsic finger muscles act across the wrist joint as well. When FDP and/or the flexor digitorum superficialis (FDS) contract, for example, they exert torque not only about the interphalangeal and metacarpophalangeal joints of the fingers, but also about the wrist.

FIGURE 3.2 EMG activity in the human FDP during individuated finger movements. EMG activity from a bipolar fine-wire electrode within FDP was recorded simultaneously with the force exerted at each fingertip during individuated flexion or extension movements of each digit. Instructed movements are indicated at the top of each column by a number indicating the instructed digit (1=thumb through 5=little finger), and a letter indicating the instructed direction (f=flexion, e=extension). Each column shows data recorded on a single trial. Looking down each column shows that the most force was produced by the instructed digit in the instructed direction, with only small amounts of force (if any) produced in the other noninstructed digits. Looking across the ten movements shows that the amount of EMG activity recorded at the electr...

Table of contents

- COVER PAGE

- TITLE PAGE

- COPYRIGHT PAGE

- METHODS & NEW FRONTIERS IN NEUROSCIENCE

- PREFACE

- DEDICATION

- EDITORS

- CONTRIBUTORS

- SECTION I: FUNCTIONAL NEUROANATOMY AND IMAGING

- SECTION II: NEURONAL REPRESENTATIONS IN THE MOTOR CORTEX

- SECTION III: MOTOR LEARNING AND PERFORMANCE

- SECTION IV: RECONSTRUCTION OF MOVEMENTS USING BRAIN ACTIVITY

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Motor Cortex in Voluntary Movements by Alexa Riehle,Eilon Vaadia in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Anatomy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.