- 424 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Representing the wide breadth academic disciplines involved in this ever-expanding area of research, this reference provides a comprehensive overview of current scientific and technological advancements in soft materials analysis and application. Documenting new and emerging challenges in this burgeoning field, Soft Materials is a unique and outsta

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Mobility on Different Length Scales in Thin Polymer Films

CONNIE B. ROTH and JOHN R. DUTCHER University of Guelph, Guelph, Ontario, Canada

I. INTRODUCTION

Thin polymer films with thicknesses of tens of nanometers are studied extensively because they provide an ideal sample geometry for studying the effects of one-dimensional confinement on the structure, morphology, and dynamics of the polymer molecules and because they are used extensively in technological applications such as optical coatings, protective coatings, adhesives, barrier layers, and packaging materials.

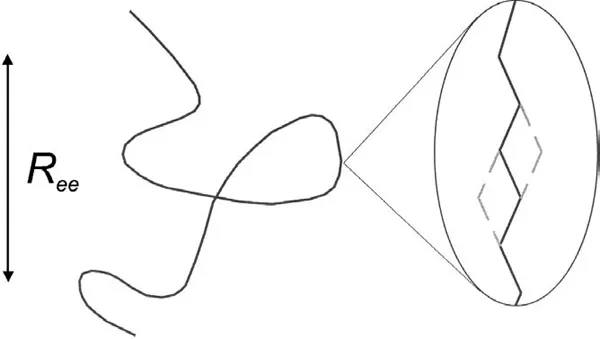

Polymer molecules can be prepared in a wide variety of different molecular architectures such as linear molecules, ring molecules, and branched molecules. The simplest molecular architecture corresponds to linear molecules that consist of identical monomer units connected end to end. In a collection of similar molecules, a linear polymer molecule will tend to form in the shape of a random coil. The overall coil size can be characterized statistically by the root-mean-square end-to-end distance Ree which scales as the square root of the length of the molecule or its molecular weight Mw, and typically ranges from several nanometers to tens of nanometers. The polymer molecule can be described by a variety of different length scales, ranging from the size of the individual monomers to the overall size of the molecule Ree (see Fig. 1). The corresponding time scales range from that corresponding to segmental relaxation, related to the glass transition, to that corresponding to the diffusion of entire chains.

In this chapter, we are concerned with the motion of polymer molecules confined to thin films. We begin by describing the basics of the motion of molecules on small length scales, which are related to the glass transition. This will be followed by discussions of mobility of polymer molecules on different length scales and the effects of confinement on molecular motion on different length scales. The remainder of the chapter contains a detailed discussion of the experimental and theoretical studies of the dynamics of thin polymer films. General trends in the data are highlighted and oustanding issues are discussed.

Figure 1 Schematic of a linear polymer molecule, including a magnification of a small number of segments of the molecule. The dashed lines indicate possible motions of the segments of the molecule.

A. The Glass Transition

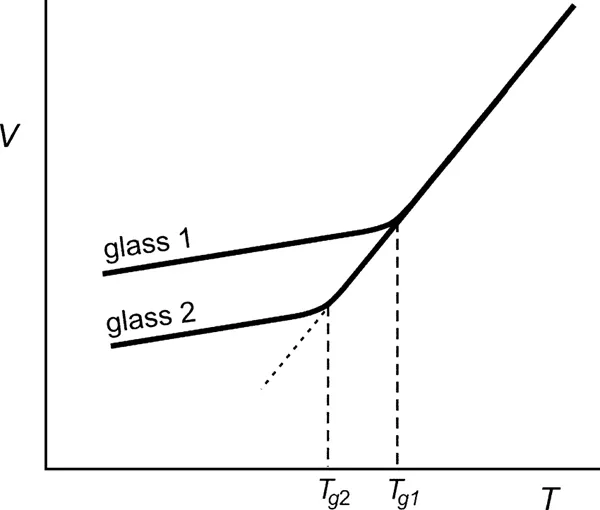

In the simplest picture, the glass transition describes the transition from a rubberlike liquid to a glassy or amorphous solid as a material is cooled. The glass transition will occur upon cooling for almost any material, from organic liquids to metals to polymers, for a sufficiently fast cooling rate. To measure the glass transition temperature Tg, it is convenient to measure the volume or heat capacity as a function of temperature (see Fig. 2). Typically, one observes an abrupt change in the slope of the temperature dependence of the volume at a certain temperature which is identified as Tg. One also finds that the glass transition temperature measured in such an experiment depends on the cooling or heating rate (see Fig. 2), as well as on the thermal history of the sample. A sample which is cooled faster falls out of equilibrium at a higher temperature, resulting in a Tgtalue that is higher than that observed for a slower cooling rate.

Figure 2 Volume V versus temperature T for a glass-forming material for two different cooling rates. Glass 1 has been cooled faster, resulting in a higher Tgtalue than that observed for the more slowly cooled glass 2.

Because of the dependence of Tgon time, the glass transition is not a true thermodynamic phase transition, but, rather, it is a kinetic transition in which the motion of the molecules is slowed so dramatically upon cooling that, at sufficiently low temperatures, no appreciable motion of the molecules can occur. The slowing of the dynamics upon cooling can be observed directly by a dramatic increase in the viscosity of the liquid. For example, the viscosity of o-terphenyl, a simple glass former, increases by nine orders of magnitude in the 30°C temperature range above Tg[1]. Unlike the large structural changes observed during the formation of a crystal upon cooling, only very subtle structural changes are observed during the formation of a glass, with the structure of the high-temperature liquid effectively frozen in with rapid cooling.

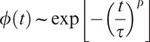

We can understand the frequency (or time) dependence of the measured Tg values if we consider structural relaxation of the material near Tg. If we consider a simplified material that has a single characteristic relaxation time s at a given temperature, then for short times or correspondingly high frequencies, no significant structural relaxation can occur during the experiment so that the material appears to be solidlike. For times that are much longer than s or correspondingly low frequencies, the material fully relaxes during the experiment so that the material appears to be liquidlike. If s increases strongly with decreasing temperature, then below a certain temperature, relaxation for that mobility mode is effectively frozen. For a glass-forming material, physical quantities such as volume or index of refraction will relax in response to a change in an experimental parameter such as temperature. At a given temperature, the relaxation function ϕ(t) can be described by a so-called stretched exponential (Kohlrausch–Williams–Watt or KWW) function:

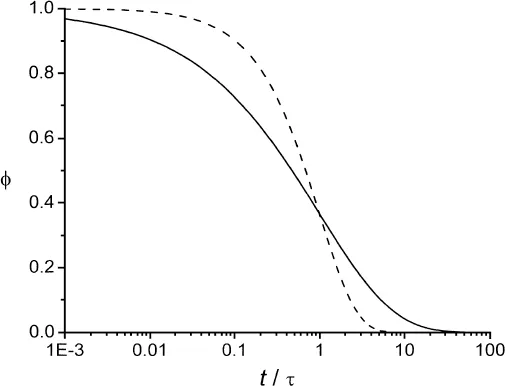

The relaxation function is shown schematically as a plot of ϕ versus tτs in Fig. 3 for two different values of β. For β = 1, the decay is a single exponential; for β<1, which is typical for glass-forming materials, the decay is nonexponential and is ‘‘stretched’’ in time compared with the exponential decay. The nonexponential behavior has two possible explanations: Either the sample is homogeneous, with each molecule obeying the same nonexpo-nential relaxation, or the sample is dynamically heterogeneous, consisting of regions with different dynamics, each obeying nearly exponential relaxation, with different regions having significantly different relaxation times. For a recent review summarizing the experimental evidence supporting dynamic heterogeneity, see Ref. 2.

As mentioned earlier, cooling of a glass-forming liquid makes it progressively more difficult for the molecules to move significantly on the experimental time scale. This dramatic slowing of the dynamics is difficult to understand theoretically [2,3]. There have been a number of different theoretical approaches to attempt to understand the glass transition, including free-volume, cooperative-motion, and mode-coupling theories. Despite these impressive efforts, no complete theory of the glass transition exists today; for a recent discussion of the relevant issues, see Refs. 3 and 4. However, there are two simple concepts that have been useful in trying to explain the dramatic reduction in molecular mobility with decreasing temperature. The basic ideas of the free-volume and cooperative-motion theories are quite simple. The motion of individual particles in a glass-forming material requires sufficient free volume into which the particles can move. As the temperature is decreased, the density increases and it becomes increasingly difficult for a particle to find sufficient free volume for motion to occur on a reasonable timescale [5]. One way to achieve motion at low temperatures is to allow a cooperative rearrangement of neighboring particles such that many particles must move together if any motion is to occur at all. Adam and Gibbs postulated the existence of cooperatively rearranging regions or CRRs as the smallest regions at a given temperature that can rearrange independent of neighboring regions [6]. In their theory, the size of the CRRs was inversely related to the configurational entropy of the system, such that the CRR size increased with decreasing temperature. Experiments indicate that the size of these regions is several nanometers [7,8]. Although the CRRs were originally envisioned as spherical volumes of diameter n, recent computer simulations have shown that the cooperative motion is essentially stringlike [9], with the average string length increasing with decreasing temperature. A shortcoming of the Adam–Gibbs approach is the assumption of no interaction between neighboring regions. Because the stringlike shape is less compact than the spherical shape, interaction between neighboring regions will be more significant and this could have a distinctive signature for the effect of confinement on the dynamic properties of glass-forming liquids.

Figure 3 Relaxation function ϕ versus t/τ for an idealized glass-forming material characterized b...

Table of contents

- COVER PAGE

- TITLE PAGE

- COPYRIGHT PAGE

- PREFACE

- CONTRIBUTORS

- 1: MOBILITY ON DIFFERENT LENGTH SCALES IN THIN POLYMER FILMS

- 2: CRYSTALLIZATION OF THIN POLYMER FILMS: CRYSTALLINITY, KINETICS, AND MORPHOLOGY

- 3: DEFORMATION, STRETCHING, AND RELAXATION OF SINGLE-POLYMER CHAINS: FUNDAMENTALS AND EXAMPLES

- 4: SCIENCE AND ENGINEERING OF NANOPARTICLE-POLYMER COMPOSITES: INSIGHTS FROM COMPUTER SIMULATION

- 5: POLYMERIC ADDITIVES AS MODIFIERS OF HYDROCARBON CRYSTALLIZATION BEHAVIOR

- 6: CONFINEMENT AND SHEAR EFFECTS ON THE STRUCTURE OF A SMECTIC LIQUID-CRYSTAL COMPLEX FLUID

- 7: MACROSCOPIC RHEOLOGICAL BEHAVIOR OF DISPERSIONS OF SOFT RUBBERLIKE SOLID PARTICLES

- 8: COMPUTER SIMULATIONS OF MECHANICAL MICROMANIPULATION OF PROTEINS

- 9: STRUCTURE-FUNCTION RELATIONSHIPS OF ASPARTIC PROTEINASES

- 10: COMPUTER SIMULATION OF SOFT MESOSCOPIC SYSTEMS USING DISSIPATIVE PARTICLE DYNAMICS

- 11: CRYSTALLIZATION OF BULK FATSUNDER SHEAR

- 12: FOODS AT SUBZERO TEMPERATURES

- 13: BIOGENIC CELLULAR SOLIDS

- 14: MODELING OF FORMATION AND RHEOLOGY OF PROTEIN PARTICLEGELS

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Soft Materials by John R. Dutcher,Alejandro G. Marangoni in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Chemistry. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.