![]()

SECTION 1

EXPLORING YOUR

RELATIONSHIP WITH TIME

![]()

Poetic Pause

Time as sunflowers

Facing the light in worship

Petaling forward

The subject of time covers everything from how long something takes to how old we are, how long we will live, and decisions about the “right time” to make choices or take action. Time is familiar to everyone, and yet it’s quite challenging to define and identify.

Modern science defines time within the term space-time in an effort to explain that coordinates in time do not exist without the corresponding coordinates in space. Space-time may therefore reference a scientific interpretation of time. To fully explain the personal experience of time, however, there are an endless number of “coordinates” that locate us in a certain moment, such as emotions, expectations, relationships, and values.

We do not live in purely sequential time, where any moment consists of the moment and that moment only. In fact, the true “present” is so brief that it can’t even be perceived. So, naturally, even when we are completely focused in the present, our awareness extends both to the past and to the future. To illustrate the brief temporality of the present, Leonardo da Vinci said, “The water you touch in a river is the last of that which has passed, and the first of that which is coming. Thus it is with time present.”

The term specious present, coined by E. Robert Kelly (aka E. R. Clay) in 1882, refers to the period that we tend to think of as the present, though it also includes the near past and upcoming future. Specious present indicates the overlap between the circles of past, present, and future. In actuality, though, our perception extends beyond the overlap of three defined circles. We can feel the fabric of time folding itself over us, or perhaps folding itself within us, at every given moment.

“I have a vision of the three bears with bowls of ‘time’ instead of porridge. Ultimately, time is precious, whether it’s going too fast, too slow, or just right.”

— SANDE ROBERTS,

ARTbundance Coach

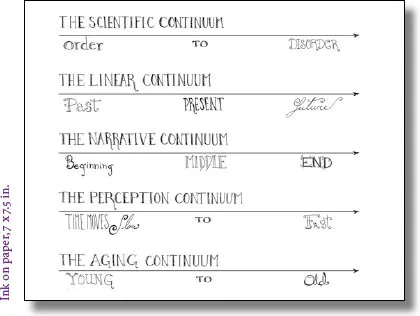

By way of example, I identified a few of the time continua that we use to measure and define time, and asked artist Michelle Berlin to illustrate them as linear timelines. As you can see, each one is represented here by an arrow facing in one direction.

Linear Time Continua

by Michelle Berlin

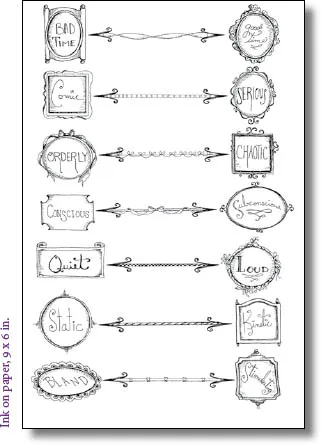

The Linear Time Continua graphs indicate a variety of quantitative continua. However, qualitative continua are more multidimensional, allowing us to measure time in an infinite number of ways. Here are some examples that come to my mind, again illustrated by Michelle:

Nonlinear Time Continua

by Michelle Berlin

Any given moment can be plotted on any combination of the above timelines, as a way to “measure” it. However, when we do so, the measurement consists not only of the “dot” itself but also of the very continuum it lies upon. No matter how we choose to measure time, any moment includes the entire time continuum. Time is not something outside of us; it is an element of everything.

THE PROBLEM WITH TIME

I asked some ACT trainees why we have time, and here are a few of their responses:

“Time allows us to see, to witness the unfolding of free will.” — Tanya Laurin

“We use time to categorize our moments, by year, era, or timeline. Time is a backdrop to place our memories in order, to make sense of the happenings that take us from here to there.” — Amy Heil

“Time makes life’s ‘little gifts’ bigger. Time is here for us to learn and heal and discover.” — Peggy Lynn

As all the statements above indicate, the structure of time allows us to see and experience life. And yet time also can blind us to greater truths, as our time-based consciousness can greatly limit our worldview.

The concept of time management is very new, just as “stress” is a modern phenomenon. Time management can improve what we accomplish but often at the peril of what we experience. As a result, the more we try to manage our time, the more fragmented we feel. If you pay attention to the conversations all around you, it’s startling how often the subject of time comes up.

“How are you?”

“Oh fine, just crazy busy…”

“You should come check it out…”

“Yeah, I know; I just don’t know when I can find the time…”

“How are you?”

“I can’t really talk now, I’m running late…”

People used to be tied to things like families, communities, rituals, worship, curiosity, and beauty. Now we are tied to schedules, watches, datebooks, computers, gadgets that start with i, the media, and exercising on treadmills that don’t go anywhere.

ARTbundance Coach Amy Heil expressed it nicely: “When we become a slave to the system of measuring time, when we are focused on too much or not enough, we are not serving our best interests. This instant is truly endangered, so the only time to focus on is now!”

Somehow the tendencies of our society make it acceptable and even expected that we fall into patterns of being worried and stressed about time. And while worrying about time seems to be part of our humanity, I wonder…does it really need to be?

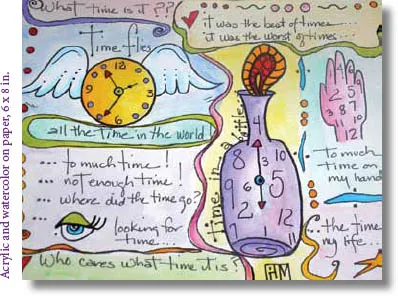

Time Collage by Patricia J. Mosca

MEASUREMENT AND PERCEPTION

One second is officially defined in atomic time as 9,192,631,770 oscillations of the “undisturbed” cesium atom. However, even with this precise number of oscillations, time is surprisingly nonuniform. There is not perfect unity between the rotation of the earth (which measures a day) and atomic time. In fact, official time often has to be put back or forward a bit to compensate.

We measure time in a variety of units, from seconds, hours, and minutes to beginning, middle, end. We also measure time according to our needs (“Is it time to eat yet?”), external demands (“When is it due?”), and anticipations (“Are we there yet?”). Regardless of how we measure time, however, that measurement is always trumped by perception. While so many of us are controlled by time, the interesting thing is that we’re rarely aware of time itself. We usually don’t know how long something takes in the moment, and yet its length is how we end up measuring it.

I was stunned at my own inability to correctly perceive time when recently I was having an MRI and was situated so that I could see a countdown timer of the scan, which I presume is there so that the patient knows how much longer she needs to stay still. I played a game of closing my eyes and opening them when I thought a minute had passed. The first time, I opened my eyes after only forty seconds. I tried again, and it had been forty-one seconds. I continued to try for each minute, and each time I was “accurate” within my own perception: I always opened my eyes at around forty seconds. It was only when I pushed myself to wait a little longer that I came closer to a minute, and I was still under sixty seconds.

Naturally, lying still in an MRI machine would qualify as one of those instances when time perception is slowed, the antithesis of “Time flies when you’re having fun.” Still, I was surprised at my experience. I suppose I shouldn’t have been; many scientific experiments have proved that individuals have a varying sense of perception of time passing. Psychochronometry is the study of the psychology of time estimation. Many studies have explored the various factors that affect time perception, including environment, emotions, and age. Studies of the Logtime Hypothesis, for example, have found that perception of the passage of time increases by the square root of one’s age, and at age sixty, time is perceived about two and a half times faster than it was at age ten.

I decided to conduct my own experiment, a casual wa...