![]()

1

Ice Age Bones

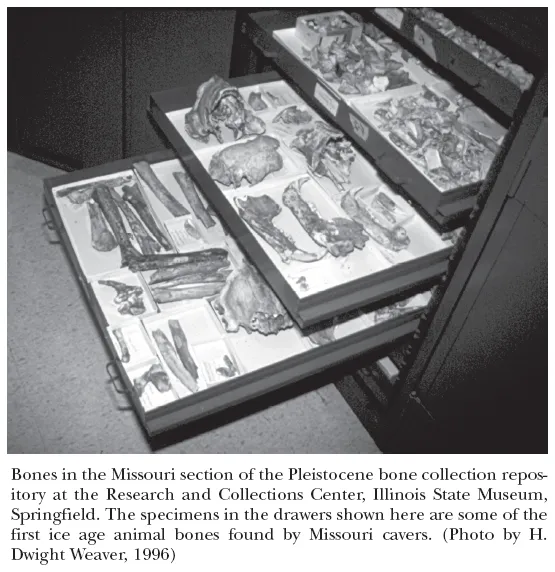

A surprisingly large number of Missourians are engaged in cave exploration. . . . These explorers have recently developed a special interest in the bones that are found in many caves, and new finds are reported so rapidly that it is difficult to keep pace with their identification and analysis.

—M. G. MEHL, Missouri’s Ice Age Animals, 1962

Since the days of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, the bones of ice age animals have been found all across Missouri. They remind us that many great beasts, now extinct, once roamed this land, including creatures such as woolly mammoths, mastodons, giant ground sloths, peccaries (ancient piglike animals), moose-elk, bison, long-legged dire wolves (which must have been terrifying), enormous cave bears, ferocious saber-toothed cats, huge American lions, and giant beavers. A surprisingly large number of fossil animal remains have been found in Missouri caves embedded in clay and gravel sediments. Some remains have been discovered lying exposed on cave floors right where the animal died thousands of years ago. In addition, the clay floors and stream banks of some caves preserve the tracks, dens, and claw marks of extinct animals.

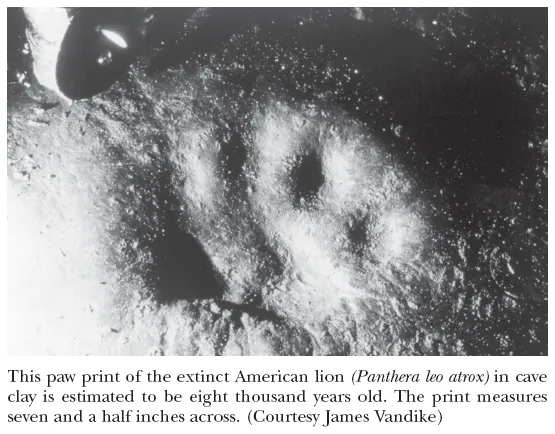

Several decades ago cavers discovered the footprints of the extinct American lion in a cave near the Missouri-Arkansas border. The species has been dead for more than eight thousand years, yet the tracks looked so fresh, according to the cavers, that seeing them raised the hair on the backs of their necks. It was easy to imagine the animal was still alive and somewhere close by in the cave. Many caves

have the ability to preserve fossil remains and tracks for a very long period of time. Another set of remarkable animal tracks preserved in clay were found in a cave near Perryville south of St. Louis—footprints believed to be those of the ice age jaguar or saber-toothed cat.

These kinds of discoveries make experienced cavers very cautious when exploring a wild cave they have not visited before or a cave known to be virgin. They pay attention to where they put their feet, because fossil imprints left in soft clay can be easily and quickly destroyed. One can only wonder how many fossil tracks of ice age, or Pleistocene Epoch, animals have been destroyed in Missouri caves over the past 150 years by careless people.

A diverse group of large animals existed here between ten thousand and two million years ago. The undisputed champions for size were members of the elephant family. The most abundant were the American mastodons and the more common ice age mammoth. These enormous creatures shared their environment with the giant

North American beaver, a muskratlike animal as large as the modern-day black bear. There were two species of ground sloth, one of them a giant, with enormous claws designed for digging and self-defense. The animal weighed a ton and stood twelve feet high on its hind feet.

Another impressive creature was the giant short-faced cave bear, which stood five and a half feet tall at the shoulders and weighed around fourteen hundred pounds. The bear was a formidable carnivore, but it was not alone as it stalked the herbivorous browsers of savanna, swamp, and woodland. The bear’s competition included saber-toothed cats, jaguars, lions, and packs of dire wolves.

These predators fed upon wildlife much different than that of present-day Missouri animals. During the ice age there were also tapirs, armadillos, camels, and crocodiles living in the area that is now Missouri. These animals probably numbered in the millions, and most of them vanished, including the predators, in a relatively short span of time. The issue of why they disappeared so quickly toward the end of the ice age is a subject of considerable scientific debate.

Throughout geologic history there have been many ice ages. The most recent one began about two million years ago. Its cause, like the extinctions of plants and animals, is still highly debatable. Why some animals grew so large during the ice age is also uncertain, but it may have had to do with the nutritional value of the vegetation they consumed and the abundance of good things to eat. Their large size may have also been an adaptation to challenges in the overall environment.

The extinction of these animals may have been caused by the changing climate, but mass extinctions are nothing new. They have occurred a number of times over the past six hundred million years. But while the older extinctions were probably due entirely to natural events unrelated to humans, it appears that some of the extinctions in Missouri did not occur until after the arrival of Native American (Paleo-Indian) groups around ten thousand to fourteen thousand years ago.

Missourians began asking questions about these fossils in the nineteenth century, when the remains kept turning up in newly plowed fields, creek gravel, river sediments, clay banks, and at construction

sites. Some of the first bones of mastodon, peccary, and ground sloth were excavated in the 1830s in eastern Missouri around Kimmswick.

Today, however, most ice age animal remains are found in caves. Animals such as mammoths and mastodons certainly did not live in caves, but their bones were often washed into caves by storm waters or their carcasses dragged into caves by predators. Sinkhole pits that dropped into caves also served as animal traps. The animals would fall in, be unable to climb out, and die of injuries or starvation. Dire wolves, bears, cats, and a few other animals probably denned in caves and dragged their prey into caves, thus leaving behind a stash of bones for today’s cavers to find and paleontologists to study.

One of the most surprising such cave discoveries occurred September 11, 2001, at Springfield, Missouri. On the very day that terrorists were destroying the World Trade Center towers in New York City, a road construction crew discovered a remarkable cave beneath the city streets of Springfield, the largest city in the Missouri Ozarks. Known today as River Bluff Cave, this unique resource contains more than a half mile of passage and is highly decorated with cave formations. It also contains a vast accumulation of ice age animal remains and footprints. Scientists now consider the cave a world-class fossil site, and it may be the oldest fossil cave in North America. This time capsule of the ice age had been sealed by natural events for thousands of years, protecting its fossil remains, which some scientists estimate to be six hundred thousand to one million years old.

The giant short-faced cave bear denned in River Bluff Cave, leaving behind its beds and mighty claw marks as well as a tale of slaughter when it preyed on flat-headed peccaries. The peccaries left behind a rare trail of footprints, bones, and feces in the cave. Even the waste matter of these ancient animals is important because it can tell us what they ate, facts about their environment, and the general nature of their health.

Fossil remains from the cave include mammoth, horse, musk ox, turtles, snakes, and the saber-toothed cat. Since this ice age “museum” has only recently been discovered, its resources have barely been researched. Who knows what discoveries are yet to be made in River Bluff Cave?

Giant cave bears and ice age cats were the first mammals to use caves in the Missouri Ozarks as dens, but mankind too would find refuge in the caves beginning around eleven thousand years ago. Prehistoric cultures would leave behind ceremonial sites, footprints, artwork, fabrics, stone and bone tools and weapons, the remains of countless meals, and even evidence of human burials in Missouri caves.

![]()

2

Prehistoric Times

If “Cave Man”. . . ever existed in the Mississippi Valley, he would not find any part of its natural features better adapted for his requirements than in the Ozark hills.

—GERARD FOWKE, Cave Explorations in the Ozark Regions of Central Missouri, 1922

Because Missouri is at the confluence of the nation’s three great heartland rivers, the Mississippi, Missouri, and Ohio, it became a crossroads for America’s prehistoric Indian cultures. Scientists estimate that the total number of archaeological sites in Missouri could be in the millions. For some counties alone, there are more than two thousand recorded sites, according to Missouri archaeologist Larry Grantham.

Water, to a large extent, determined where prehistoric groups settled or had temporary campsites. It had a major impact upon their environment, their food, and their physical prosperity. These factors, in turn, influenced their social structure, material culture, religion, and trade patterns. Prehistoric Indians, like the American and European settlers who came after them, tended to live along rivers and close to freshwater spring outlets. Missouri caves and rock shelters are most frequently found in bluffs, in sinkhole basins, and along hillsides of streams and rivers. Spring outlets, regardless of their size, are simply cave openings that discharge groundwater.

By definition, a cave generally has an opening that is deeper than it is wide and penetrates the hill, whereas a rock shelter is a hollow that is generally wider than it is deep without a cave component. There are exceptions since both characteristics can be part of the same natural feature or closely associated with it. There are many rock shelter archaeological sites throughout Missouri and many of them have produced prehistoric materials. The number of cave sites that contain prehistoric material is definitely fewer in number. Yet some cave sites are highly significant because cave environments often preserve materials for a long period of time. This depends, of course, upon the composition of the prehistoric material. Good examples are the finds at Arnold Research Cave, also known as Saltpeter Cave, in Callaway County.

John Phillips, one of the first settlers of Callaway County, settled near the present town of Portland and took possession of this cave in 1816 for the purpose of making gunpowder from the cave’s saltpeter deposits. The cave subsequently became known as Saltpeter Cave. Some years later, H. E. Arnold came into possession of the Saltpeter Cave property, and by the early twentieth century the cave was known as Arnold Cave. Long noted for the beauty of its entrance, which has a graceful arch of sandstone spanning two hundred feet, the entry chamber leads to several additional rooms within the hill that are connected by low-ceiling crawlways.

Professional archaeological excavation began at the cave in the mid-1950s. Since then it has been called Arnold Research Cave. The excavations resulted in the discovery of prehistoric materials dating back seven thousand to ten thousand years. Among the finds were more than thirty specimens of perfectly preserved moccasins and slip-on shoes estimated to be nine thousand years old. The moccasins were made of leather while the other shoe-types were woven from fibrous plants. Such finds are uncommon, because most archaeological sites yield only prehistoric materials made of stone and bone. The dry, dusty condition of the cave deposits containing the preservative elements of saltpeter may have been partially responsible for the excellent state of preservation of the shoes.

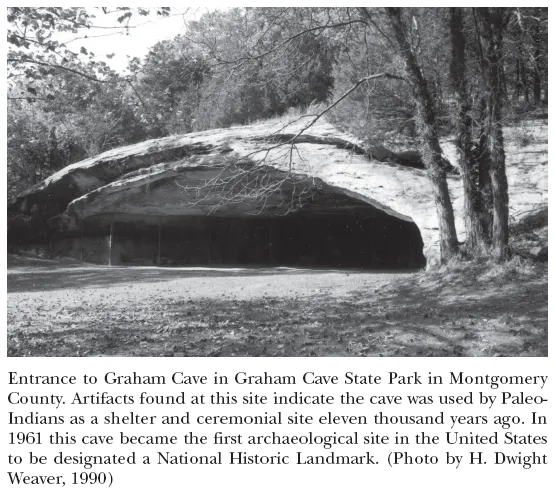

Not far away, in adjacent Montgomery County, is Graham Cave, which was formed in the same St. Peter Sandstone formation as Arnold Research Cave. Graham Cave, however, does not have internal chambers and is more easily classified as a rock shelter. It is now the centerpiece of Graham Cave State Park. Artifacts found in the shelter cave are as much as ten thousand years old, according to radiocarbon dating technology.

Archaeologists have divided the span of time between the appearance of the first Indians in Missouri and the arrival of European settlers into periods that reflect major cultural advances among these vanished people. They include the hunters of the Paleo-Indian Period, 12,000–8000 BC; the hunter-foragers of the Dalton Period, 8000–7000 BC; the foragers of the Archaic Period, 7000–1000 BC; the prairie-forest potters of the Woodland periods, 1000 BC–AD 900; and the village farmers of the Mississippian periods, AD 900–1700.

Most of these cultures used caves from time to time as campsites, as refuges from winter cold and summer heat, as a source for flint to make weapons and tools, and as a source of water, clay for pottery, and minerals that had ceremonial and medicinal uses. Native Americans left pictographs (prehistoric drawings or paintings) and petroglyphs (prehistoric carvings and inscriptions) on some Missouri cave walls. According to Carol Diaz-Granados and James R. Duncan, in The Petroglyphs and Pictographs of Missouri, about one-third of Missouri’s known rock-art sites are “located on the inner or outer walls of caves and rock shelters.”

Very few people think of Missouri caves as graveyards, but some caves contain Indian burials. Such burials are of special interest to professional archaeologists and their associates in their pursuit of the secrets of Missouri’s prehistoric past. Unfortunately, the burials are also of interest to unethical collectors who seek Indian artifacts and grave goods for profit. Professional archaeologists have a word they use to describe unprincipled, profit-motivated artifact collectors—looters. These grave robbers seldom keep records of their finds and make no effort to report their discoveries.

No one knows for certain just how many of Missouri’s current 6,200 recorded caves contain Indian burials. In order to protect the cave resources from looters, no list of such caves has been made public. But it is safe to assume that scores of Missouri caves have yielded Indian remains over the past two hundred years.

Early European and American settlers who mined Missouri caves for saltpeter were probably the first to happen upon prehistoric burial sites, because they had reason to excavate cave soils. From the beginning of European settlement, it was “open season” on Indian artifacts and graves. The collecting of antiquities, as Indian artifacts were then commonly called, evolved into a popular pastime. Digging in caves to find artifacts and burials became a popular activity, and the market for antiquities blossomed. The average antiquities collector in the late 1800s and early 1900s felt no regret about plundering artifact sites and taking Native American grave goods and body parts because of their belief that the Indians were uncivilized and racially inferior to whites.

Unfortunately, elements of this attitude have survived to the present day, because Indian artifact and burial sites in Missouri caves are still the focus of looters, who often do their digging at night or with posted lookouts during the daytime. They operate in the Ozark hills in much the same fashion as moonshiners once did and methamphetamine manufacturers do today, creating a dangerous situation for anyone who might happen upon them unexpectedly.

Digging up Indian artifact and burial sites on federal or Indian tribal land without proper authority is in violation of federal law, in particular the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation of Cultural Patrimony Act (November 1990). Even digging up unmarked graves on private land or in caves in Missouri without the proper authority is a violation of Missouri law. Missouri law defines such burials as “any instance where human skeletal remains are discovered or are believed to exist, but for which there exi...