eBook - ePub

The Foundation of the CIA

Harry Truman, The Missouri Gang, and the Origins of the Cold War

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Foundation of the CIA

Harry Truman, The Missouri Gang, and the Origins of the Cold War

About this book

This highly accessible book provides new material and a fresh perspective on American National Intelligence practice, focusing on the first fifty years of the twentieth century, when the United States took on the responsibilities of a global superpower during the first years of the Cold War. Late to the art of intelligence, the United States during World War II created a new model of combining intelligence collection and analytic functions into a single organization—the OSS. At the end of the war, President Harry Truman and a small group of advisors developed a new, centralized agency directly subordinate to and responsible to the President, despite entrenched institutional resistance. Instrumental to the creation of the CIA was a group known colloquially as the "Missouri Gang," which included not only President Truman but equally determined fellow Missourians Clark Clifford, Sidney Souers, and Roscoe Hillenkoetter.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Foundation of the CIA by Richard E. Schroeder in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

American National Intelligence

From the Revolutionary Army to World War II

DURING EARLY CRISES IN THE history of the United States, especially the American Revolution and the Civil War, national leaders recognized the need to find ways to better understand—and thus more easily defeat—enemies. Both the work of understanding foreign adversaries and the secret organizations that do so are called “intelligence.” Many modern professionals consider General George Washington to have been the country’s first director of national intelligence because he took such a personal interest in recruiting and managing spies to better understand his British opponents. Early American leaders like Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson quickly learned the skills of intelligence collection, analysis, and influence when they were dispatched abroad to European capitals, first and foremost as diplomats but equally important as collectors of useful secret information and advocates trying to persuade powerful Europeans to support the struggling American rebellion.

But if wartime leaders understood the need to understand their enemies, American leaders and generals in the first century of the republic quickly forgot those lessons as soon as the conflict had ended. European Great Powers had, however, been rivals for centuries, and in countries like England, France, and Russia, the skills of spying on other countries were almost as well developed as skills in creating new weapons and managing great armies and fleets. As an example, by the end of the American Civil War, the Union army was as well led and skillful as any fighting force in the world, and the American navy had a fleet as modern as any European rival. European observers watched these American advances with great interest, and they applied American lessons to their own countries. Within twenty years, however, as the United States focused its energy on absorbing millions of immigrants and developing the vast stretches of the American West, the navy shrank to such a state that even Brazil had a more powerful and advanced fleet, and in 1889 the American navy ranked as the twelfth largest in the world. Still, American naval officers observed foreign technological developments and naval conflicts with great attention, and they sent their reports back to Washington. Problems quickly arose, however, because each American observer had different opinions of foreign developments, and they sent those opinions to different offices within American naval headquarters. These offices, in turn, had different views about how the navy should spend its money and focus its meager resources, and Congress took unhappy note of this confusion. The last decades of the nineteenth century were a time of revolutionary technological advancement, and these advances were leading Europeans to build great battleships of such massive size, strength, and firepower that they were the superweapons of the period. The United States might have been a country with a flourishing international maritime trade, but without a real navy to defend the country against foreign fleets—or a clear picture of possible foreign threats—American ships or even coastal cities were vulnerable to destruction.

Therefore, in early 1882 the secretary of the navy directed the creation of an Office of Intelligence,1 to be combined with the departmental library to collect and record information that would be useful to the navy in time of war or peace. All naval officers were directed to use “all opportunities . . . to collect and forward” what today would be called foreign naval intelligence.2 Aside from officers on ships visiting foreign ports, the navy even sent officers to American embassies overseas to report on naval matters. The secretary directed that “only such officers as have shown an aptitude for intelligence staff work, or who by their intelligence and knowledge of foreign languages . . . give promise of such aptitude, should be employed.” Reports from overseas all came back to this new Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI),3 where overworked “clerks” could then analyze them, advise the secretary and Congress, and even publish a monthly bulletin to inform naval officers about the latest foreign developments. Today, the officers in the field would be called “collectors,” and the clerks “analysts,” but it took many decades, and many failures, to develop the very different skills needed by these two very different but equally important professions. And it took just as long to create the government organizations that would provide secret foreign intelligence to government leaders and Congress, and for those “customers” to understand and support these secret organizations.

The United States was delighted by the navy’s success in the Spanish-American War of 1898, which left America occupying Cuba and the Philippines, but many Americans were alarmed by Japan’s success in defeating Russia’s fleet just seven years later in 1905. Anti-Asian feeling ran very high in California, especially after the great San Francisco earthquake in April 1906, and anti-Japanese laws and riots offended and angered Japan. War hysteria arose in popular newspapers in both countries, with the Japanese asking, “Why do we not insist on sending ships” to protect Japanese Americans from “the rascals of the United States, cruel and merciless like devils.” President Theodore Roosevelt, a former assistant secretary of the navy, wanted a larger US fleet, but he raged at “the infernal fools in California” who

insult the Japanese recklessly and the worse than criminal stupidity of the San Francisco mob, the . . . press, and . . . the New York Herald. I do not believe we will have war, but it is no fault of the . . . [tabloid] press if we do not have it. The Japanese seem to have about the same proportion of . . . prize [supernationalist] fools that we have.4

Californians became so frightened by the idea of Japanese naval attacks on their cities, in fact, that in 1907 Roosevelt used their appeals for help as an excuse to send his new American battle fleet around Cape Horn to the West Coast as part of his audacious plan to send the “Great White Fleet” around the world to demonstrate American strength and technology. Naval intelligence officers accompanied the fleet, taking careful note of all the South American and Asian navies that welcomed their visit, although one young intelligence officer wrote his mother, “Please don’t tell anyone that officers . . . do such things because some people might think it wasn’t . . . courteous.”5

Just a few years later, in 1914, the Great War broke out in Europe, finding the United States not only unprepared but unwilling to become involved.6 By now the Great White Fleet was shockingly obsolete, especially compared to the British and German battle fleets, and in any case Americans themselves were undecided about where their sympathies lay. The large number of German immigrants, especially in the Midwest, were naturally drawn to support their fatherland, and most Irish Americans were hostile to Great Britain because of British policy in Ireland. Because the products of American farms and factories were vital to the warring camps, both Germany and England tried very hard to influence the United States. German agents were especially aggressive in trying to recruit spies and saboteurs,7 while the British tried to charm the American government while easily breaking and reading coded American diplomatic messages.8 Thanks to the efforts of the new Bureau of Investigation (later named the Federal Bureau of Investigation [FBI]) and the United States Secret Service, President Woodrow Wilson gradually became aware of efforts by German diplomats to secretly influence American newspapers, subsidize Irish American and German American organizations, and plant bombs in ships bound for Great Britain. Both German army and naval attachés were involved, especially the very active German naval reserve officer Franz von Rintelen, who boasted, “I’ll buy what I can and blow up what I can’t.”9 In 1915 Wilson wrote: “I am sure that the country is honeycombed with German intrigue and infested with German spies. The evidence of these things are multiplying every day.” He even worried “that there might be an armed uprising of German sympathizers. Rumors of preparations for such a thing have frequently reached us.”

Although trying hard to remain neutral, Wilson couldn’t ignore the evidence of German attempts to subvert Americans, especially since the British, who had captured von Rintelen on his way back to Germany, were adding alarming details to the information gathered by the Bureau of Investigation and the Secret Service. At the end of 1915, therefore, the United States expelled the German army and naval attachés. The secretary of state, Robert Lansing, complained of “attacks upon . . . American industries and commerce through incendiary fires and explosions in factories, threats to intimidate employers and other acts of violence.” As he told President Wilson, “I feel we cannot wait any longer to act. . . . We have been overpatient with these people.”10

The most shocking events turning not only the American people but also the government against Germany were the sinking by a German submarine of the British ocean liner Lusitania in 1915—with the loss of more than one hundred Americans—and the explosion of two million pounds of munitions meant for Russia on Black Tom Island in New York Harbor in 1916. German sabotage showed how vulnerable the United States was, but also that the American police and security services were all but incompetent. Not only were the Secret Service and Bureau of Investigation understaffed, underfunded, and undertrained, but they feuded with each other so much that they would not share information. For his part, Secretary Lansing proposed to create an information center in his department, telling President Wilson that the agencies were “willing to report to the State Department but not each other.” This was not the first or last time that rivalries between government organizations would weaken American intelligence efforts. This was also not the last time that more sophisticated foreign intelligence officers benefited from American inexperience. In fact, the British intelligence chief in New York, Sir William Wiseman, soon won Wilson’s confidence so powerfully that later a senior British officer called Wiseman “the most successful ‘agent of influence’ the British ever had.”11

Because much German sabotage was directed against American shipping or port facilities, in 1916 the assistant secretary of the navy, Franklin Roosevelt, gained approval to create a group of naval investigators to be stationed in each domestic naval district to guard against enemy activity, detect foreign spies, and protect American property and interests.12 Initially, these counterintelligence officers were volunteer reservists rather than professional naval officers, and in 1929, more than a decade later, Missouri businessman Sidney Souers—later Harry Truman’s first director of central intelligence—joined their ranks.

When the United States entered World War I on April 6, 1917, there were only a handful of US naval attachés stationed abroad, and those in Germany and Austria were expelled. Other offices in Europe were quickly opened, however, and the Office of Naval Intelligence needed candidates with foreign-language skills and experience. As Lieutenant Colonel James Breckinridge, the first US Marine naval attaché in Scandinavia, later said:

We need two things, and we need them badly. These are a knowledge of languages away and beyond the usual American ability to stutter. . . . We are a joke in any international gathering. . . . The other thing is to have a small class in which to teach what intelligence duty is. . . . To begin with, [attachés] should know the language fluently, know the history of the people and the country, something about their social conditions and persuasions, their national ambitions and prejudices . . . . They then will be at home. . . . If [the attaché] is prepared for that sort of work, there is no limit to what he can do.13

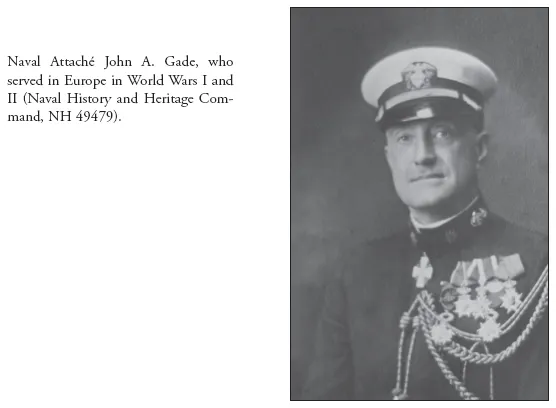

One of the best-qualified of those new candidates was John Allyne Gade, the son of an American mother and Norwegian diplomat father. He grew up in Norway, was educated in France and Germany, studied architecture at Harvard University, and practiced successfully in New York until World War I inspired him to join an American aid organization in German-occupied Belgium. Aside from his humanitarian work, he engaged in anti-German intelligence “mischief” with Belgian secret agents. Once the United States entered the war, Gade was given a navy commission and made assistant naval attaché in Oslo, responsible for Norway and Sweden. Soon he was promoted to naval attaché in Denmark, and he made good use of his native Norwegian to recruit sailors who had access to very important information about German naval activities in the Baltic and North Seas. It was also extremely helpful that the admiral commanding the Danish coast guard was an old family friend. Gade worked closely with allied attachés but “found it humiliating to realize what a greenhorn I was in comparison with my [British and French] colleagues.”14

Although the United States might have been new to the ruthless world of wartime espionage, Gade learned quickly. Ordered to steal the codes from the German embassy in Copenhagen, Gade learned that the senior German diplomat had a weakness for pretty women. He suggested finding a woman to seduce the German but was rebuked by the secretary of the navy himself for suggesting something so immoral. The navy, indeed the United States in general, had very ambivalent feelings about secret activities, from the young Great White Fleet intelligence officer who worried that collecting information about foreign navies was discourteous, to the secretary of the navy, the secretary of state, and the president—all of whom considered intelligence ungentlemanly. Undeterred, Gade learned from a naval intelligence colleague in New York about a young German American nurse who would agree to help Gade steal the codes. She was successful, and the codes were passed to Herbert Yardley, the father of modern American code-breaking and the US Army’s chief cryptologist. A few weeks later the German diplomat caught the nurse copying more German codes, but Gade and a Danish naval officer were able to smuggle her out of the German embassy and then across the Baltic Sea to ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword

- Introduction

- Chapter One. American National Intelligence: From the Revolutionary Army to World War II

- Chapter Two. America in World War II and the Beginnings of Central Intelligence

- Chapter Three. William J. Donovan and the Office of Strategic Services

- Chapter Four. Harry Truman, Sidney Souers, and the Next Steps

- Chapter Five. The CIA, Roscoe Hillenkoetter, and the Cold War

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index